Exhibition to Reveal da Vinci’s Invisible Drawings

The UK show will mark the largest display of da Vinci’s work in more than 65 years

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/1d/371d1f28-77d3-469b-bc40-f30f76c81465/912380-cardiff.jpg)

So far as we know, Leonardo da Vinci completed fewer than 20 paintings in his lifetime. But the leading Italian Renaissance artist did leave behind thousands of drawings, which he used to prepare for his artworks, record his observations and illustrate various projects and ideas. As Kate Brown reports for Artnet News, a major exhibition in the UK is displaying a trove of the artist’s sketches—and revealing the secrets hidden within da Vinci’s work.

Titled Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawings, the exhibition will showcase some of the most precious items in the Royal Collection Trust. Starting in 2019, different selections of twelve drawings will be displayed simultaneously in venues across the U.K. Then, in time for the 500th anniversary of da Vinci’s death that May, the drawings will be gathered together for a show at the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace. This exhibition, which boasts a total of 200 sheets, will be the largest display of da Vinci’s work in more than 65 years.

According to Hannah Furness of the Telegraph, the drawings belonging to the Royal Collections have been kept together since 1590, when they were bound into an album by the Italian sculptor Pompeo Leoni. The pieces on display provide examples of all of the drawing materials that da Vinci used: pen, ink, chalk, watercolor and metalpoint. The drawings also offer a glimpse into the mysterious mind of a revered artist who left very few completed works behind.

“[Da Vinci] was respected as a sculptor and architect, but no sculpture or buildings by him survive,” the Royal Collection said in a statement. “[H]e was a military and civil engineer who plotted with Machiavelli to divert the river Arno, but the scheme was never executed; he was an anatomist and dissected 30 human corpses, but his ground-breaking anatomical work was never published; he planned treatises on painting, water, mechanics, the growth of plants and many other subjects, but none was ever finished. As so much of his life's work was unrealized or destroyed, Leonardo's greatest achievements survive only in his drawings and manuscripts.”

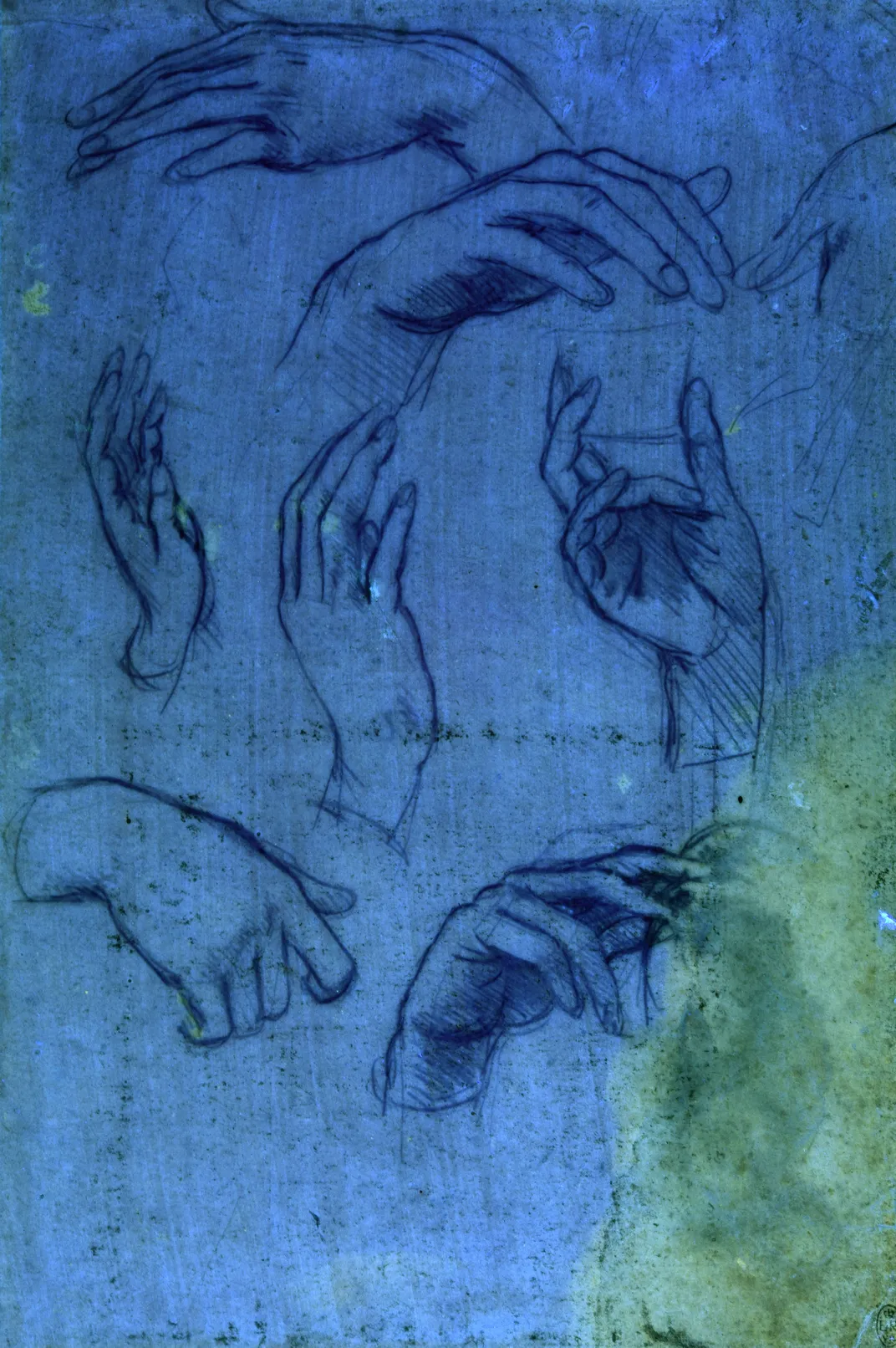

Those lucky enough to visit the exhibition might be surprised to see two completely blank pages on display. But there is more to these beguiling relics than meets the eye. Using ultraviolet light, experts were able to uncover faded sketches of hands, each one posed differently: fingers raised, palms outstretched, knuckles curled and so on. Da Vinci drew these illustrations while preparing to paint The Adoration of the Magi, which he painted circa 1481. The exhibition will include a photograph showing the infrared image of da Vinci’s original sketch.

“It was discovered that the drawings had become invisible to the naked eye because of the high copper content in the stylus that Leonardo used – the metallic copper had reacted over time to a become a transparent copper salt,” the Royal Collection explains. Another metalpoint drawing, completed with a silver stylus, remains completely visible to this day.

Non-invasive imaging technologies have allowed modern scholars to gain other insights into da Vinci’s artistic process. One of the works on display, titled “Studies of water,” was revealed to have been built up in stages, becoming increasingly complex. First, da Vinci drew swirling water currents in chalk, later adding a frothy torrent of bubbles in ink. “A Deluge,” also on show at the exhibition, began as a frenetic storm of black chalk, which da Vinci later refined with patterns of rain and waves drawn in brown ink.

Because the centuries-old drawings are quite fragile, they are rarely put on display. Martin Clayton, head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, says in the statement that he hopes “as many people as possible” will take this rare opportunity to see these remarkable works.