The Little-Known Story of 16th- to 18th-Century Nordic Witch Trials

An art exhibition in Copenhagen and a museum in Ribe revisit witchcraft’s legacy in Denmark and neighboring countries

:focal(800x449:801x450)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/79/74790974-6193-42ab-bd33-b8725ea72841/durer.jpg)

Fire, smoke and wood surround a young woman tied to a stake. As the flames creep closer, she strains against her bonds, fruitlessly hoping to escape her impending fate. Her skin sizzles, and her terrified screams pierce the air before fading into silence.

This scenario may sound like the beginning of a horror movie or a nightmare, but in late Renaissance and Enlightenment-era Europe, it was an all-too-familiar sight, with tens of thousands burned at the stake for witchcraft. Some were lucky enough to be strangled, hanged or beheaded prior to facing the flames, but many were left to endure the full horrors of the sentence.

Almost 240 years after Europe’s last execution on charges of witchcraft, an exhibition at Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen, Denmark, seeks to shed light on 16th- through 18th-century witches and witchcraft trials in the Nordic region. Titled “Witch Hunt,” the show juxtaposes contemporary commissions with historical works by the likes of Albrecht Dürer and Claude Gillot.

“The participating artists explore discriminatory fear and hatred as it spreads from both the bottom up and the top down—between neighbors onto larger communities and from governments to other political institutions, questioning how such narratives are often written out of history,” says the gallery in a statement. “At a time of global unrest, as the politics of commemoration are in question, ‘Witch Hunt’ suggests the need to revisit seemingly distant histories and proposes new imaginaries for remembering and representation.”

As alluded to by the statement, representation is a key aspect of the witchcraft narrative. Between 70 and 80 percent of individuals accused of witchcraft in Europe were women, writes scholar Suzannah Lipscomb for History Extra; she adds, “[B]ecause women were believed to be morally and spiritually weaker than men, they were thought to be particularly vulnerable to diabolic persuasion.”

“Witch Hunt” recontextualizes this trend, scrutinizing the biased nature of witchcraft trials and drawing attention to oft-overlooked “incidents of indigenous violence” in Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland, per Caroline Goldstein of artnet News.

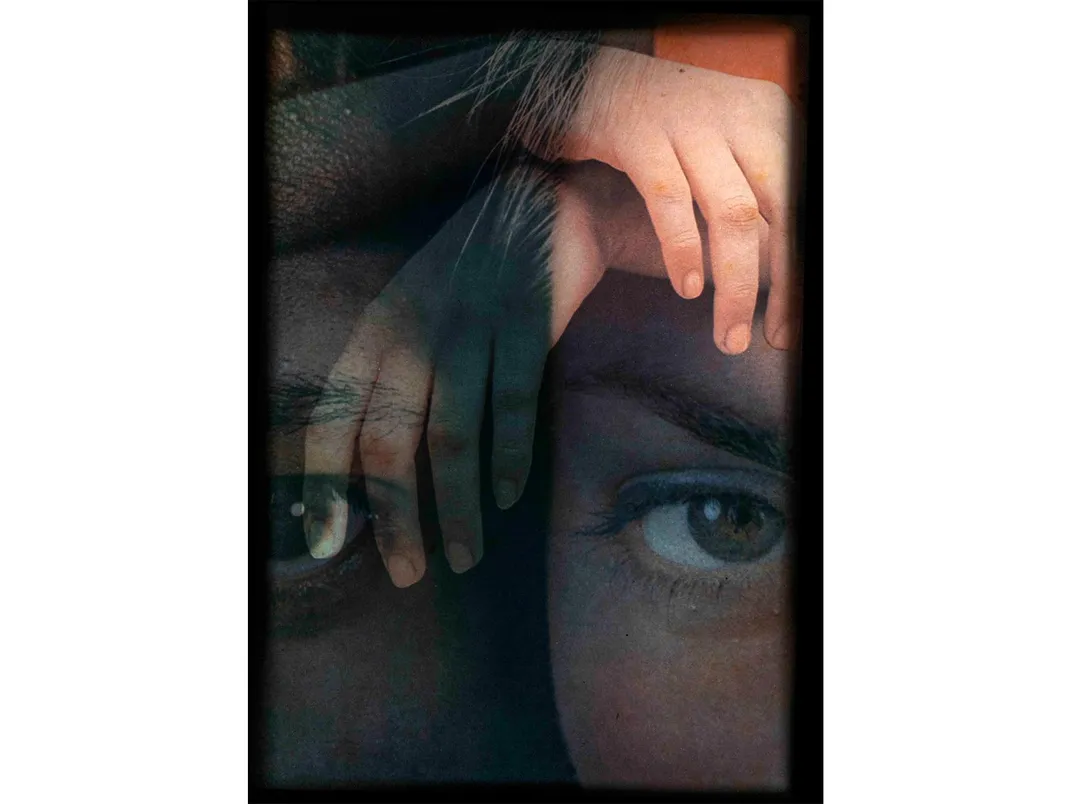

Featuring such female artists as Louise Bourgeois, Carol Rama, Carmen Winant and Aviva Silverman, the exhibition contextualizes works of art on view by presenting scholarship and archival materials that detail the social, gendered and geopolitical aspects of Nordic witchcraft trials.

“From the impact of Danish colonialism to the multifaceted violences of misogyny, the exhibition proposes a present haunted by persecutions of the past—but one that is also occupied by new critical voices of opposition,” says Kunsthal Charlottenborg in the statement.

Some pieces in the show—such as Máret Ánne Sara’s Gielastuvvon (Snared)—appear to explicitly reference the vicious history of the trials. In the 2018 work, noose-like lassoes hang from the ceiling, offering viewers an eerie reminder of the fate that some witches faced. (In Salem, Massachusetts, for instance, accused witches were hanged rather than burned.) Others, like Albrecht Dürer’s 1497 De fire hekse (The Four Witches), are less immediately arresting but still illuminating.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/17/1b17f82a-1719-4fa1-8a33-02c3b2618642/gielastuvvon_photo_liborgalia-copy-1_1.jpg)

In Denmark specifically, around 1,000 individuals were executed as witches, wrote Jimmy Fyfe for the Copenhagen Post in 2016. Though the practice of witchcraft itself emerged as part of Danish culture as early as 1100, witch-hunting hysteria peaked during the 16th and 17th centuries, when the Protestant Reformation was in full force.

Denmark’s Christian IV introduced an ordinance “against witches and their accomplices” in 1617. According to a 2011 paper by Louise Nyholm Kallestrup, a historian at the University of Southern Denmark, the legislation “prohibited all forms of magic, benevolent as well as malevolent,” and emphasized the public’s “obligation to denounce witchcraft to the courts.”

During the eight years following the ordinance’s adoption, Denmark’s number of witchcraft trials increased, with accused individuals burned at the stake roughly every five days, per Agence France-Presse (AFP). Witch hunts only fell in popularity in the second half of the 17th century, when skepticism among the upper classes precipitated their decline.

Kunsthal Charlottenborg isn’t the only Danish cultural institution revisiting the region’s history of witchcraft. In June, Hex! Museum of Witch Hunt opened in the town of Ribe. As AFP reports, the museum—located in the house of a former witch hunter—features witchcraft-related objects ranging from brooms to amulets, dolls and torture devices.

“Interestingly, the ‘historic truths’ pertaining to the witch hunt era have since been blurred and reinterpreted by more popular notions of the topic,” museum historian Louise Hauberg Lindgaard tells AFP, “and we can definitely feel the desire to understand ‘what actually happened’ among our guests.”

“Witch Hunt” is on view at the Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen from November 7 to January 17, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/08/42087b6b-d369-4649-92af-11a18dbdc7e2/8322.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)