How Has Photography’s Relationship With Nature Evolved Over the Past 200 Years?

A new exhibition at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery features more than 100 works documenting the natural world

:focal(1164x1189:1165x1190)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/35/3935fca8-da43-49c3-9079-bc7d2673a17c/ugiuhsdaf.jpg)

Withered flowers droop slightly, their leaves curling up like quotation marks. A young plant takes its first stretch toward the sun, slowly unfurling its nascent leaves. Scattered beans lie flat on a table, casting long, gray shadows on its surface.

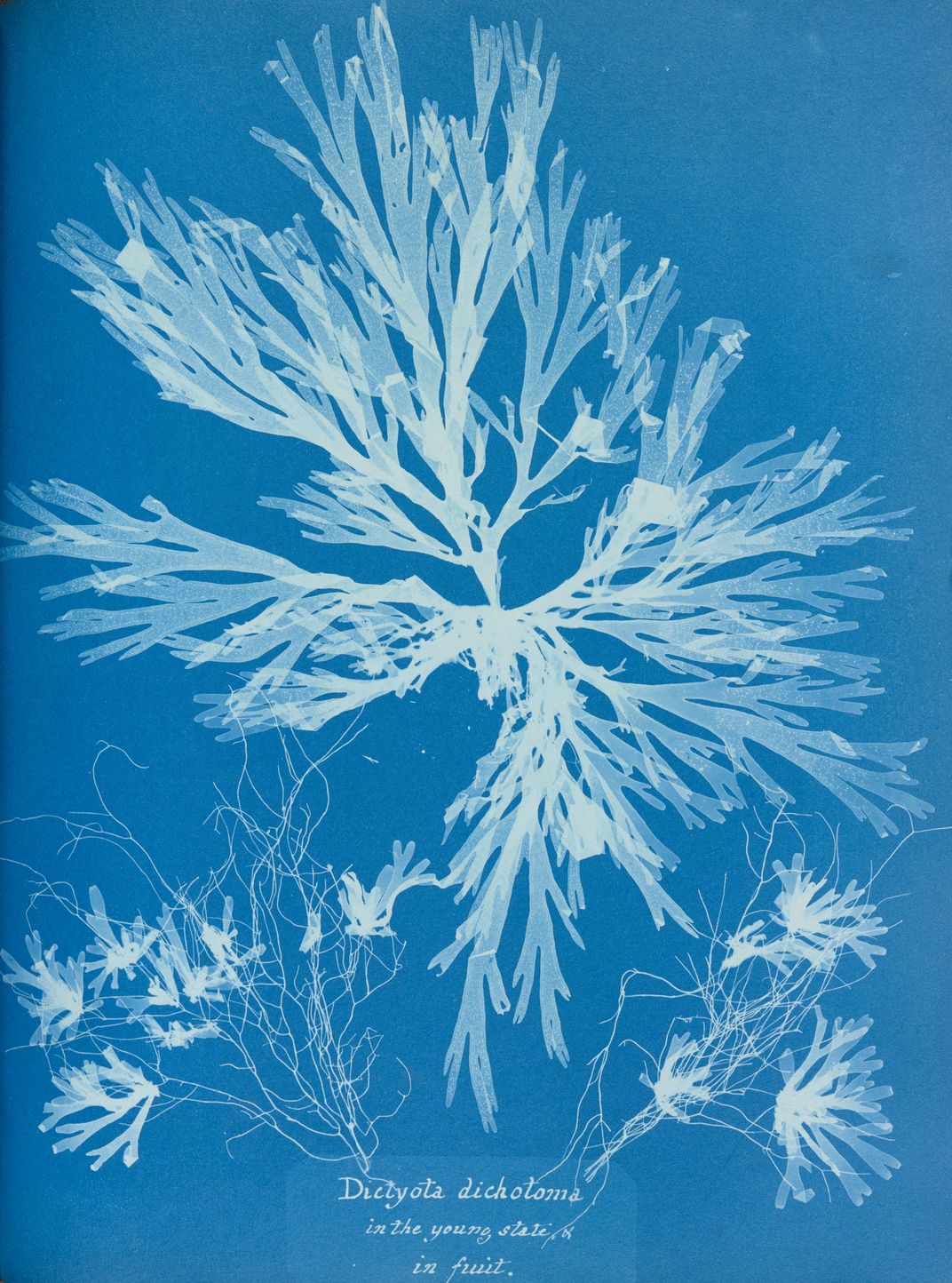

These are just a few of the scenes depicted in a new exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London. Titled “Unearthed: Photography's Roots,” the display acts as an informative showcase of the medium’s “almost symbiotic relationship with the natural world,” writes Laura Cumming for the Observer. It features more than 100 works by 41 international artists, including William Henry Fox Talbot, Imogen Cunningham, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Charles Jones. Also spotlighted is Anna Atkins, a 19th-century British botanist who was the first person to illustrate a book with photographic images.

Per a statement, many of the images in “Unearthed” focus on botany and science. Selections demonstrate how their creators drew inspiration from nature, using photographic technology to capture pictures that experimented with color and composition. The chronological format of the exhibition also allows viewers to explore the history of photography between the 1800s and the present day, tracing the image’s evolution from a documentary tool for scientists to an artistic means of expression and—more recently—manipulation-prone digital file.

“There is beauty to be found in all of the works in the exhibition, which includes some new discoveries,” says curator Alexander Moore in a statement. “More than anything though, this exhibition reveals nature as the gift that keeps on giving—a conduit for the development of photography, it is also a force for hope and well-being that we have come to depend on so much in recent months.”

Jones (1866–1959), a relatively obscure pioneer of botanical photography, was better known in life as a gardener. Collector Sean Sexton only rediscovered Jones’ oeuvre in 1981, when he purchased a trunk containing several hundred of the photographer’s prints, wrote Jonathan Dyson for the Independent in 1998. According to the Michael Hoppen Gallery, which hosted a 2015 exhibition on Jones, “[t]he extraordinary beauty of each Charles Jones print rests in the intensity of focus on the subject and the almost portrait-like respect with which each specimen is treated.”

In Bean Longpod (1895–1910), now on view in “Unearthed,” the titular plant cuts through the center of the composition, leaving little room for anything else. Other works play with their subjects’ placement: Broccoli Leamington (1895–1910), for instance, finds large broccoli heads sitting atop one another in a pyramid-like formation. The overall effect of this unusual treatment, notes the Michael Hoppen Gallery, is the “transformation of an earthy root vegetable into an abstracted” object worthy of adulation.

Because Jones left behind few insights on his artistic process, much about the stunning images’ creation remains unknown. But as the Observer reports, the photographer “would scratch the glass plates clean after the printing process for reuse, like the practical gardener he was. Some of his plates even ended up as cloches for seedlings.”

Kazumasa Ogawa (1860–1929), an innovative Japanese photographer who “effectively colored photographs” 30 years prior to the invention of color film, according to the statement, has 11 works in the show. Per the Public Domain Review, the artist combined photomechanical printing and photography techniques to create his painterly floral scenes. In Chrysanthemum (1894), three spindly, bubblegum pink flowers stand in sharp contrast to a creamy white background. The shallow depth of the photograph lends it a soft quality heightened by the addition of hand-colored pastels.

Early photographers often focused on stationary objects like plants, which were easiest to capture in an era when lengthy exposure times were the norm. Nineteenth- and 20th-century artists worked their way around these limitations, creating photographic still lifes reminiscent of Old Master paintings.

Other works in the exhibition—including Richard Learoyd’s Large Poppies (2019) and Ori Gersht’s On Reflection (2014)—highlight how modern artists continue to draw inspiration from nature.

“Perhaps the desire to photograph the vegetable world brings its own peace,” writes the Observer. “… But perhaps it also has something to do with the profound connection between photography and photosynthesis. The very light that gives life to a rose, before its petals drop, is the same light that preserves it in a death-defying photograph.”

“Unearthed: Photography's Roots” is on view at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London from December 8 to May 9, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/9b/8d9b9570-be61-4566-8e12-e26676728852/ziu7evuq.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/35/de359338-29d8-46df-af23-3319a9c5fc2c/charles_jones_-_broccoli_leamington.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/7a/617adcc9-a78b-422b-b28f-d80cf2347797/gv9ixzsq.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)