Why Was This Egyptian Mummy Encased in Mud?

Researchers have never previously observed the unusual, low-cost embalming method

:focal(1037x904:1038x905)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/0d/290da532-5abb-48b3-8c78-7d262ea86e40/mummy_mud.jpg)

The mummification of elite ancient Egyptians was a complicated, expensive process that sometimes included coating the body in a shell of imported resin. But as Garry Shaw reports for the Art Newspaper, new research suggests that a cheaper embalming option may have been available to lower-status Egyptians: mud.

“People of lesser means had more limited recourse to expensive imported resins, especially in the quantities needed to create a protective shell over the body,” write the researchers in the journal PLOS One. “However, emulation of elite burial practices could be attained through the use of cheaper, locally available alternatives.”

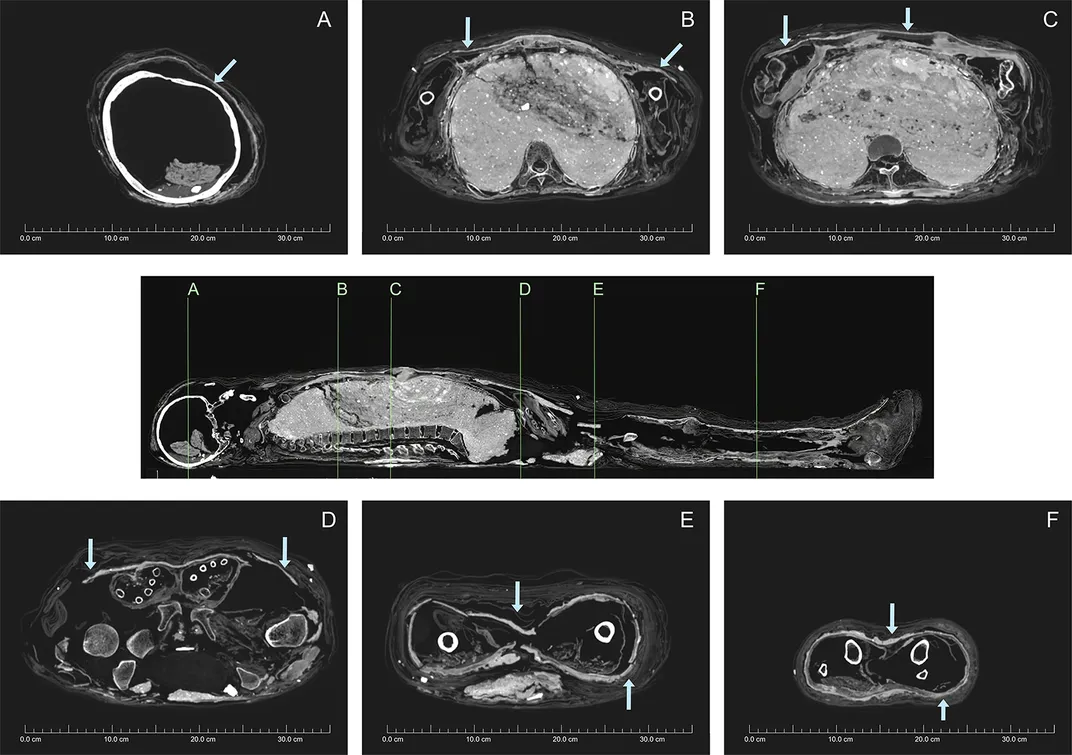

For the study, the team analyzed the mummy of a woman who was 26 to 35 years old at the time of her death. Radiocarbon dating and evidence of the mummification process place her demise sometime in the 12th century B.C., between about 1200 and 1113.

According to the researchers, the “mud carapace” discovered beneath the woman’s wrapping was not part of her original mummification. Instead, it was added decades later, after the mummy was damaged—likely by someone robbing her tomb. The repair job involved placing a mixture of mud, sand and straw between the linen wrappings and coating the shell in white, calcite-based and red ocher pigments.

“The mud was apparently applied in sheets while still damp and pliable,” lead author Karin Sowada, an archaeologist at Macquarie University in Sydney, tells Live Science’s Laura Geggel. “The body was wrapped with linen wrappings, the carapace applied, and then further wrappings placed over it.”

Embalmers may have added the shell to help hold the body together. This “bodily integrity” was key to ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, which claimed that the body must be preserved whole to ensure immortality, according to Nature.

“Status in Egyptian society was in large part measured by proximity to the king,” Sowada tells Science News’ Maria Temming, adding that the embalmers’ emulation of elite mummification processes may have been intended as a display of status.

Little is known about the origins of the mummy beyond the fact that English Australian politician Charles Nicholson donated it to the University of Sydney in 1860. Per Live Science, the coffin that now holds the mummy didn’t originally belong to it. In fact, the sarcophagus is more recent than the body, dating to around 1000 B.C. and bearing an inscription of a woman’s name: Meruah or Merutah.

“Local dealers likely placed an unrelated mummified body in the coffin to sell a more complete ‘set,’ a well-known practice in the local antiquities trade,” the researchers write in the study.

Today, the mummy is housed in the University of Sydney’s Chau Chak Wing Museum. In 1999, a CT scan revealed that the wrappings were unlike others previously found, but it wasn’t until 2017, when researchers rescanned the mummy with more advanced techniques, that they began discovering details of the mud casing.

Per History.com, while the most elaborate treatments of the ancient Egyptian dead were reserved for elites, people of all social classes mummified their loved ones. For the poor, that might just mean filling the bodies with juniper oil to dissolve their organs. As National Geographic’s Andrew Curry writes, embalmers at the Saqqara necropolis, operating centuries after the time of the newly analyzed mummy, appear to have offered “discount packages to suit every budget.” Services included evisceration, burial and care for the souls of the dead.

No other mummy is known to have been encased in a mud shell, but the study’s authors say the finding may prompt new research to investigate how widespread the practice was.

“This is a genuinely new discovery in Egyptian mummification,” Sowada tells Live Science. “This study assists in constructing a bigger—and a more nuanced—picture of how the ancient Egyptians treated and prepared their dead.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)