New Study Restructures the Dinosaur Family Tree

Detailed analysis of dino fossils suggests that Tyrannosaurus and its relatives may be on the wrong side of the tree

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/cc/56cc7884-f245-41cf-84db-d1b09a155160/dino_hips.jpg)

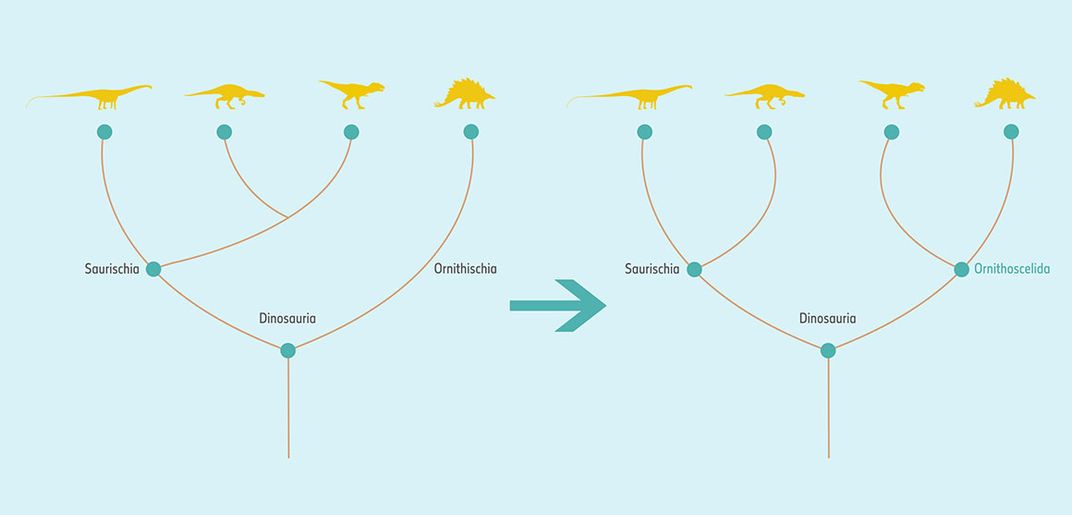

Back in 1887, British paleontologist Harry Seeley changed the dinosaur world when he began classifying the thunder lizards into two broad categories based on their hip structure.

The group he dubbed saurischians had pelvic structures similar to modern day lizards and includes theropods (large meat eaters like Tyrannosaurus), Herrerasauridae (smaller meat-eaters) and the massive sauropodomorphs (which include the 70-ton Argentinosaurus). The second group, ornithischians, have pelvic structures superficially similar to modern birds, and include classic armored dinos like Stegasaurus and Triceratops.

But a new study published this week in the journal Nature suggests that Seeley's system, which has been in place for some 130 years, isn't quite right. And the suggestion is shaking up the dino world. As Ed Yong writes for The Atlantic, "this is like someone telling you that neither cats nor dogs are what you thought they were, and some of the animals you call 'cats' are actually dogs."

So how did the study's authors arrive at this revelation? Researchers from the University of Cambridge and Natural History Museum in London analyzed the skeletons of 75 different dinosaur species, collecting 35,000 data points about 457 physical traits. What they found is that the theropods (a group that eventually gave rise to modern birds) are in the wrong group. Based on their analysis these creatures should be moved in with the ornithischians and this new bunch could be renamed Ornithoscelida.

“When we started our analysis, we puzzled as to why some ancient ornithischians appeared anatomically similar to theropods,” Cambridge grad student Matt Baron, lead author of the study, says in a press release. But the results of their analysis suggest that the similarity is more than just superficial. "This conclusion came as quite a shock," he says.

“If we’re correct, this study explains away many prior inconsistencies in our knowledge of dinosaur anatomy and relationships,” says Paul Barrett, museum paleontologist and co-author of the study.

“Luckily, most of what we’ve pieced together about dinosaurs—how they fed, breathed, moved, reproduced, grew up, and socialized—will stand unchanged,” Lindsay Zanno from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, who was not involved in the study, tells Yong. However, she says “these conclusions lead us to question the most basic structure of the entire dinosaur family tree, which we have used as the backbone of our research for over a century. If confirmed by independent studies, the changes will shake dinosaur paleontology to its core.”

There are several noticeable changes right off the bat, David Norman, researcher at the University of Cambridge and co-author of the study, explains in a press release. “The bird-hipped dinosaurs, so often considered paradoxically named because they appeared to have nothing to do with bird origins, are now firmly attached to the ancestry of living birds.”

The move also explains why some ornithischians have some indication that they may have had feathers, according to a press release from the Natural History Museum in London. If theropods and ornithischians come from one common ancestor, it means feathers only evolved once, instead of evolving separately in the two major branches of the dino tree.

The research also indicates that the first dinosaurs may have evolved 247 million years ago—a bit earlier than the current 231 to 243 million range, Yong explains. The study raises other questions, too. In the old system, ornithischians were considered plant eaters while all the meat eating dinosaurs were saurischians, meaning that the trait of eating meat could have evolved after the two main branches of dinosaurs split. But in the new system, meat eaters appear on both branches, making it more likely that the common ancestors of both branches were omnivores. Since potential omnivorous ancestors can be found in both the northern and southern hemispheres, the new association hints that the dinos didn't necessarily originate in the southern half as previously believed.

One possibility for their last common ancestor, writes Devlin, is a cat-sized omnivore called Saltopus elginensis, unearthed in a quarry in Scotland. Max Langer, a respected paleontologist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil tells Devlin that he’s not convinced that Saltopus is the mother of dinos. “There’s nothing special about this guy,” he says. “Saltopus is the right place in terms of evolution but you have much better fossils that would be better candidates for such a dinosaur precursor.”

Other researchers are now digging into the data set to see if the new classification holds up. “Whether this new family tree sticks or not will be a matter of testing,” Brian Switek, author of My Beloved Brontosaurus tells Devlin. “One group of scientists has come up with what is no doubt a controversial hypothesis, and now others will see if they get the same result, or if the idea is bolstered by additional evidence.”