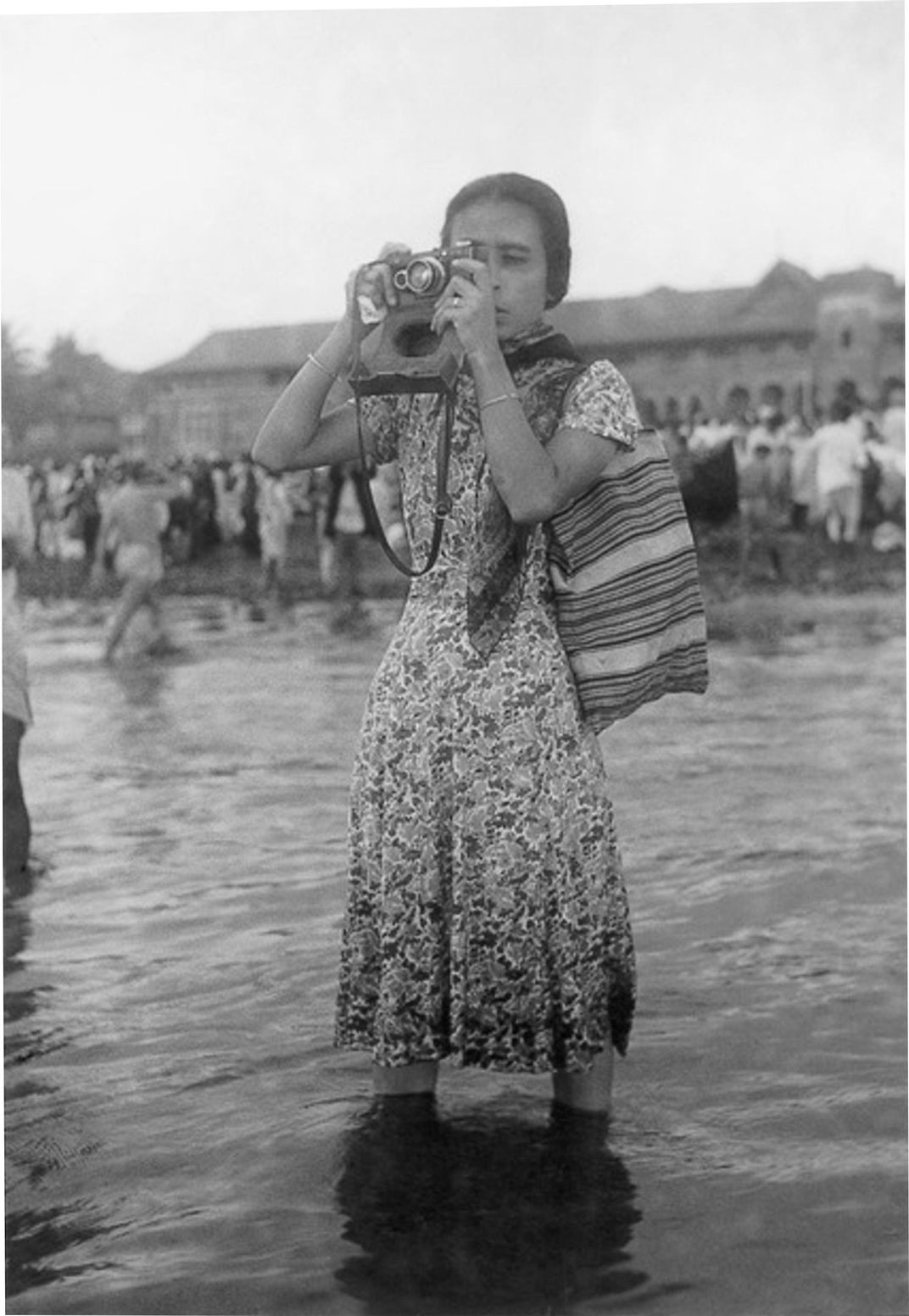

During the 20th century, Homai Vyarawalla broke ground as India’s first prominent female photojournalist. With her camera, she recorded life in modern Mumbai, taking candid photos of celebrities like Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and snapping spectacular scenes of India’s first moments as an independent nation.

But Vyarawalla’s presence in a male-dominated field often took onlookers by surprise.

“When they saw me in a sari with a camera hanging around, they thought it was a very strange sight,” she once recalled in an interview. “And in the beginning, they thought I was just fooling around with the camera.”

The photographer adds, “They didn’t take me seriously.”

Across the globe, many of Vyarawalla’s female peers faced similar hurdles, from casual misogyny to ingrained sexism in the photography world. Despite these challenges, writes Cath Pound for BBC Culture, women photographers shaped the field as it’s known today through their studio practices, daring journalism and creative innovation.

Art enthusiasts can take an encyclopedic journey through this history in “The New Woman Behind the Camera,” now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The show will run through October before traveling to the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, D.C., where it will remain on view through January 2022.

Per a statement, Vyarawalla numbers among 120 photographers included in the exhibition. Representing more than 20 countries, all were active between the 1920s and ’50s—a tumultuous period marked by economic uncertainty and a global war.

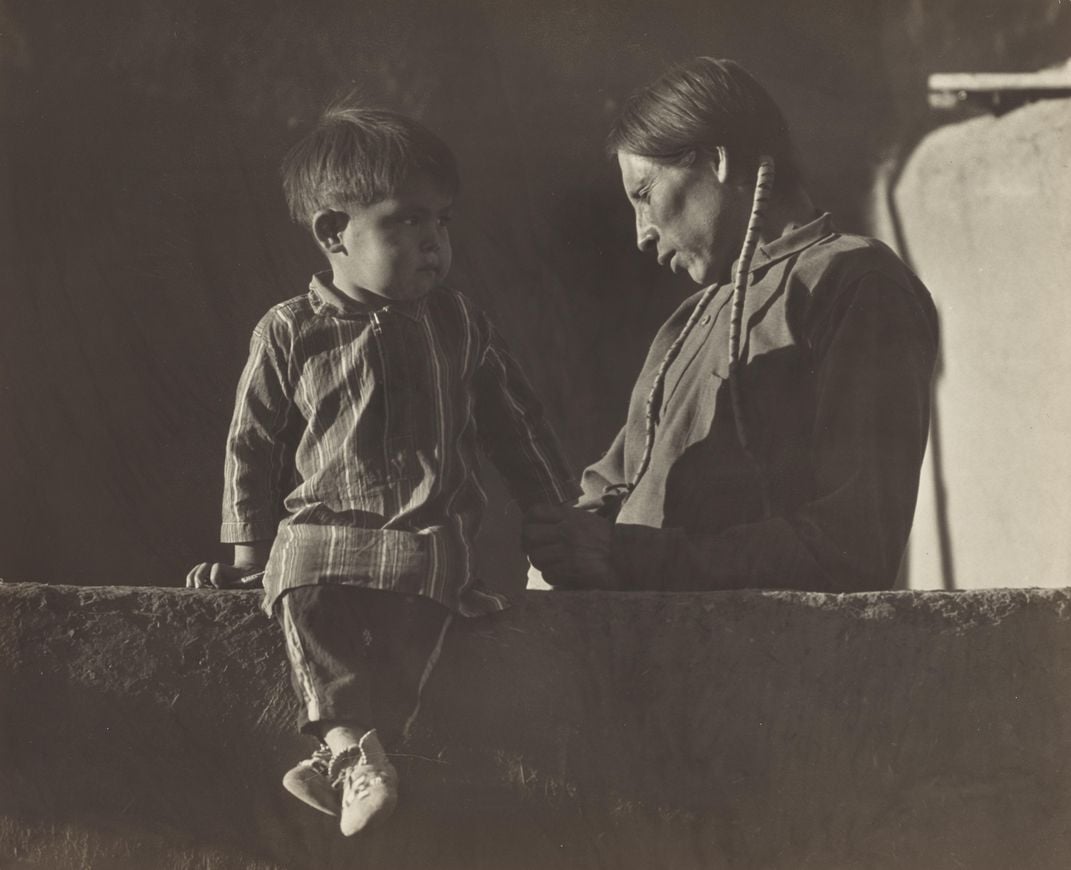

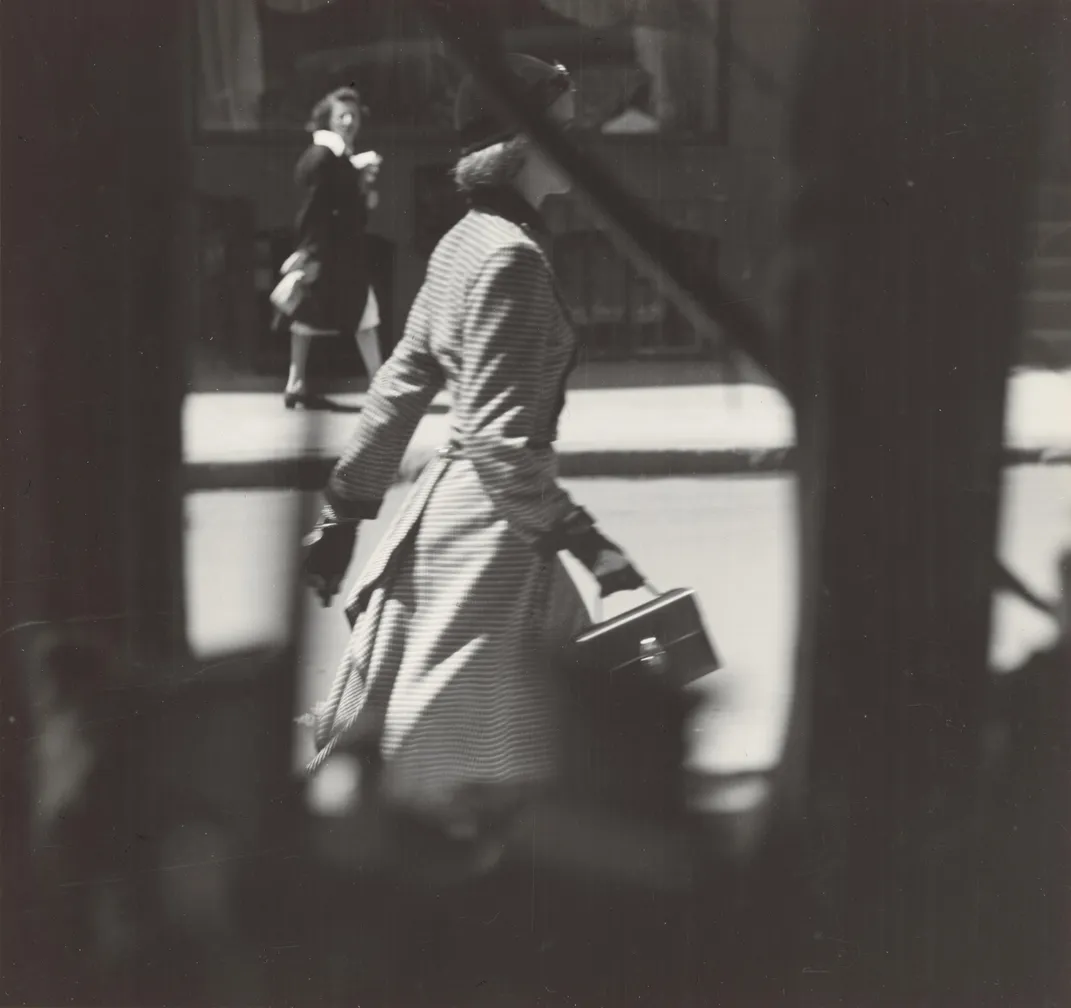

Among the artists featured are Ilse Bing, the German avant-garde photographer known as the “queen of the Leica” for her skilled street photography; Tsuneko Sasamoto, Japan’s first female photojournalist; and Karimeh Abbud, who made a living taking elegant domestic portraits in Palestine.

NGA curator Andrea Nelson tells the Art Newspaper’s Nancy Kenney that she hopes the exhibition reframes the story of modern photography as an international one.

“What I really wanted to do was hopefully move beyond the Euro-American narrative that has really structured the history of photography,” she says. “I just felt that there wasn’t a look at the greater diversity of practitioners during the modern period. So, I took off down that road.”

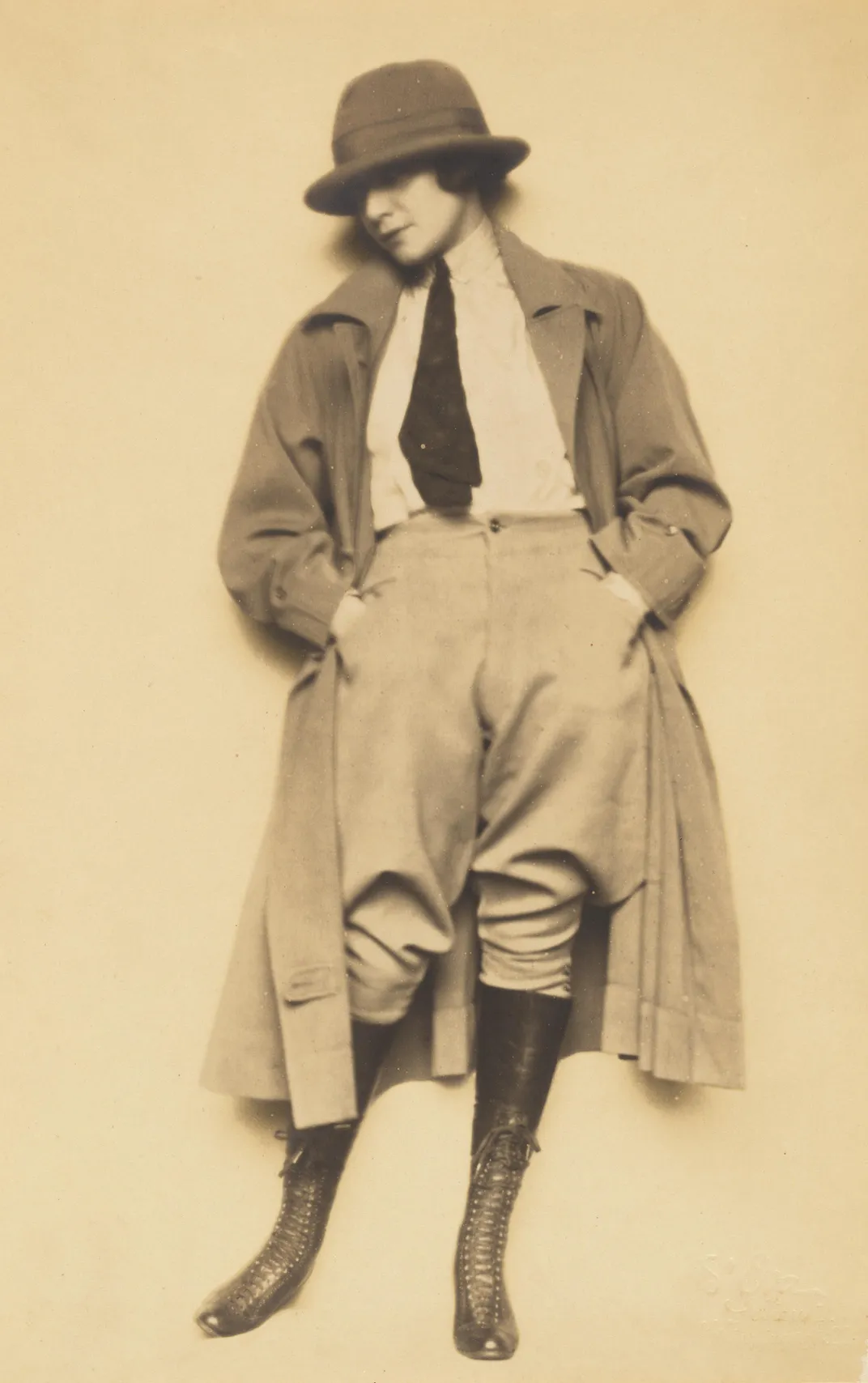

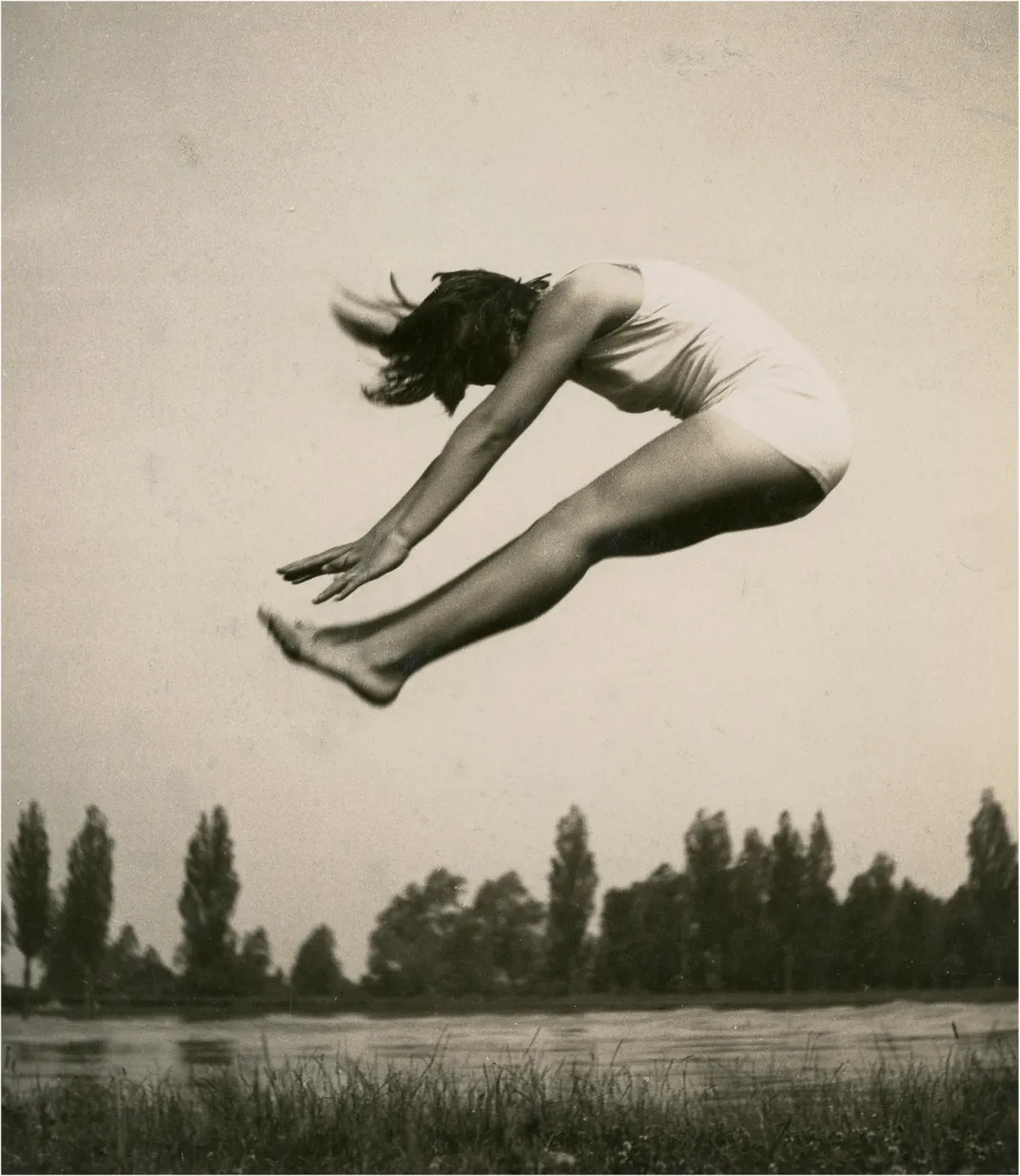

The show takes its title from the “New Woman” ideal that cropped up in different forms around the world at the turn of the 20th century.

Typically characterized by bobbed hair, androgynous outfits and an attitude of confidence, New Women challenged entrenched gender roles and “took on roles and responsibilities—new personas and even new powers—they’d rarely had before,” writes Blake Gopnik for the New York Times. (Austrian fashion photographer Madame d’Ora created an iconic image associated with the archetype in her 1921 portrait of illustrator Mariette Pachhofer, per the BBC.)

“Though the New Woman is often regarded as a Western phenomenon, this exhibition proves otherwise by bringing together rarely seen photographs from around the world and presenting a nuanced, global history of photography,” says Met director Max Hollein in the statement.

Many photographers during this period experimented with Modernist strategies, employing new perspectives, creative cropping, collage techniques and multiple exposures to make fascinating new images. The era of fashionable empowerment also coincided with a rise in cheaper, portable cameras that allowed more women to record themselves and their cities—such as Vyarawalla in Mumbai or Helen Levitt in New York City—as they saw fit.

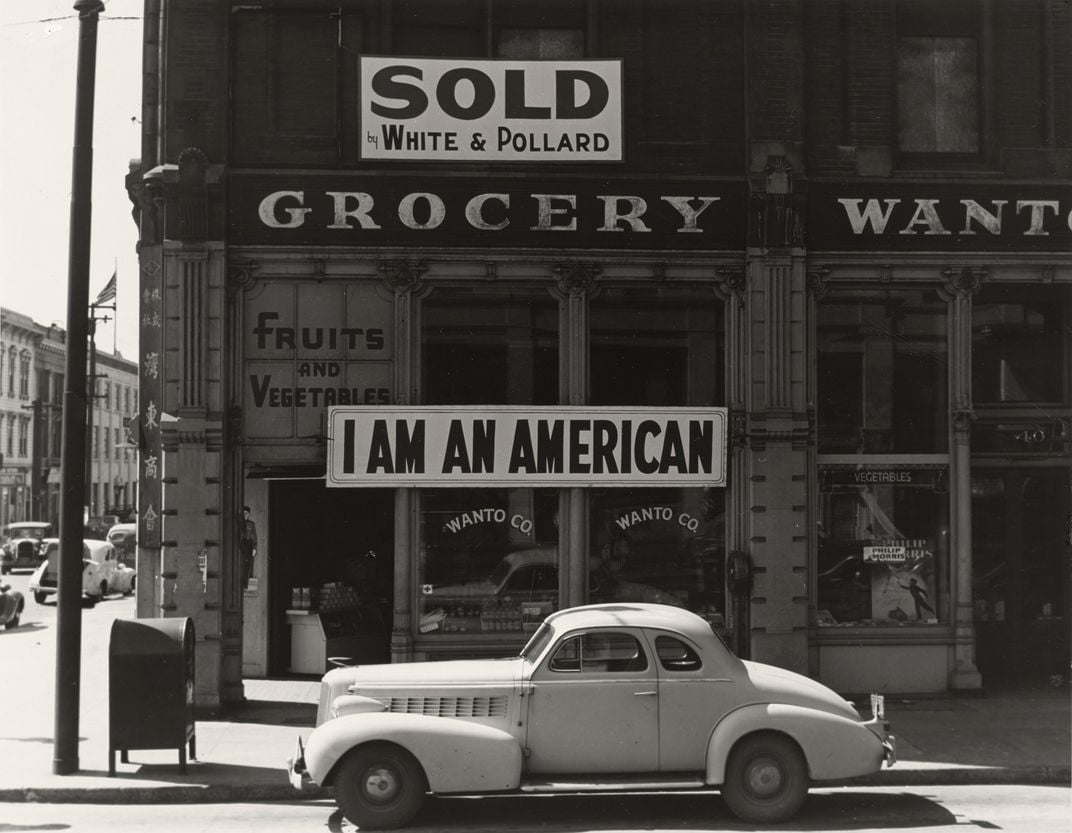

Around the same time, governments and news outlets employed increasing numbers of women: the United States’ Farm Security Administration, for instance, commissioned some of American photographer Dorothea Lange’s most iconic works during the Great Depression.

As economic roles shifted, women influenced the domestic and commercial photography industries by operating their own studios. In 1920, photographer Florestine Perrault Collins opened a studio that catered to African American families in New Orleans—likely the only one run by a Black woman in the city. She depicted her subjects with dignity and respect, resisting racial stereotypes and helping Black families preserve their genealogies for years to come, according to the Art Newspaper.

Women also bore witness to some of the century’s greatest disasters. In Japan, Sasamoto chronicled life in Hiroshima following the dropping of an atomic bomb; in post-World War II Europe, Lee Miller captured “unsparing” images of liberated Nazi concentration camps. Chinese photojournalist Niu Weiyu created moving images of ethnic minorities and women in the newly formed People’s Republic of China.

Some of the photographers in the show were eventually pushed out of the field. Sasamoto’s career was cut short when she married an unsupportive husband, according to the BBC.

Mexican photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo might have been alluding to these pitfalls of the patriarchy in In Her Own Prison (1950), which shows a woman gazing out of an open window, crisscrossed by a grid of shadows that resembles prison bars, per the Times.

Speaking with the Art Newspaper, Nelson notes that while this exhibition gathers many underrecognized women photographers together, the scholarship is far from complete. Many of the women included in the show remain understudied.

“It’s for future scholars to … dig into, to flesh out these stories and present deeper investigations,” she adds.

“The New Woman Behind the Camera” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City through October 3. The show will be on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. from October 31 to January 30, 2022.

:focal(314x165:315x166)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/49/9349b741-a44c-4973-a01a-1a942f335081/mobile_photog.png)

:focal(600x262:601x263)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/62/5462f01b-c3a7-4650-8f1e-f8d9b9b5ebc0/womenphotogsocial.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)