See Maurice Sendak’s Little-Known Designs for the Opera and Ballet

A new exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum explores how the ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ author pivoted to a career in set and costume design

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/69/1c695c76-fefd-4c8b-8c5d-1e2ae7c3734e/sendak-press-25_mlm90975_405306v_0001.jpg)

Maurice Sendak—best known for the 1963 picture book Where the Wild Things Are—had a knack for creating worlds ostensibly manufactured specifically for children but, upon closer inspection, revealed to be much like our own. As Wallace Ludel writes for Artsy, the author and illustrator shared a key tendency with his target audience: an “instinct to shield oneself from suffering by layering it with absurdity and beauty.”

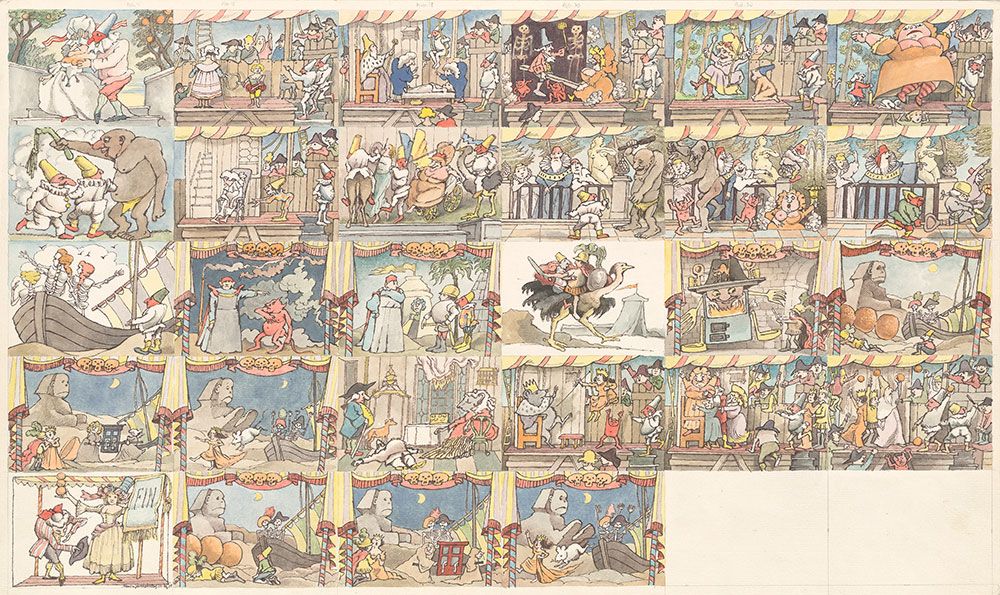

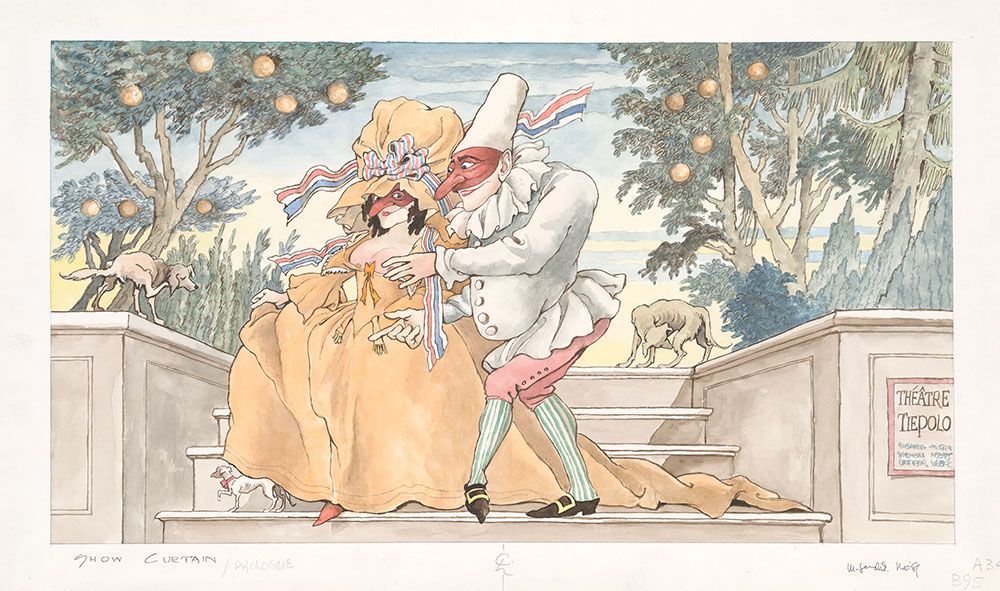

A new exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City draws on a lesser-known period of the artist’s life to emphasize this tension between fantasy and pragmatism. Titled Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet, the show brings together more than 150 works of art, including preliminary sketches, storyboards, watercolors and painted dioramas, dating to Sendak’s late-in-life stint as a set and costume designer. Per a Morgan press release, Drawing the Curtain is the first museum exhibition to focus solely on the artist’s work with the opera and ballet.

In the late 1970s, Sendak began collaborating with director Frank Corsaro on the Houston Grand Opera’s production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Sendak was a self-professed fan of the classical composer, once declaring, “I know that if there’s a purpose for life, it was for me to hear Mozart,” and he jumped at the chance to work with Corsaro on the production. According to Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times, Corsaro had not known about Sendak’s interest in Mozart when he reached out; instead, he sought him out because he knew he could build a world suited to the opera’s alternately fanciful and somber tone.

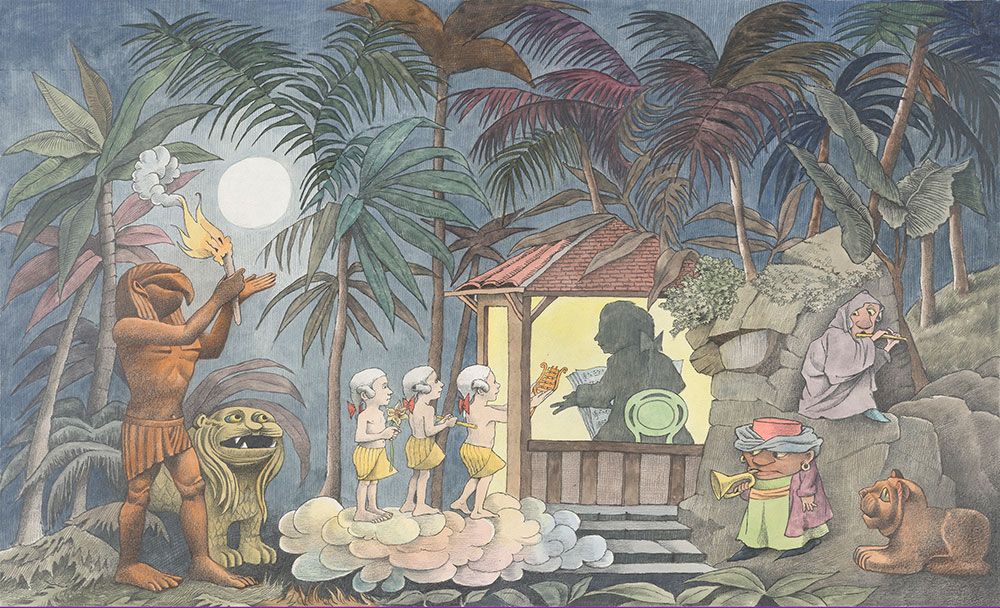

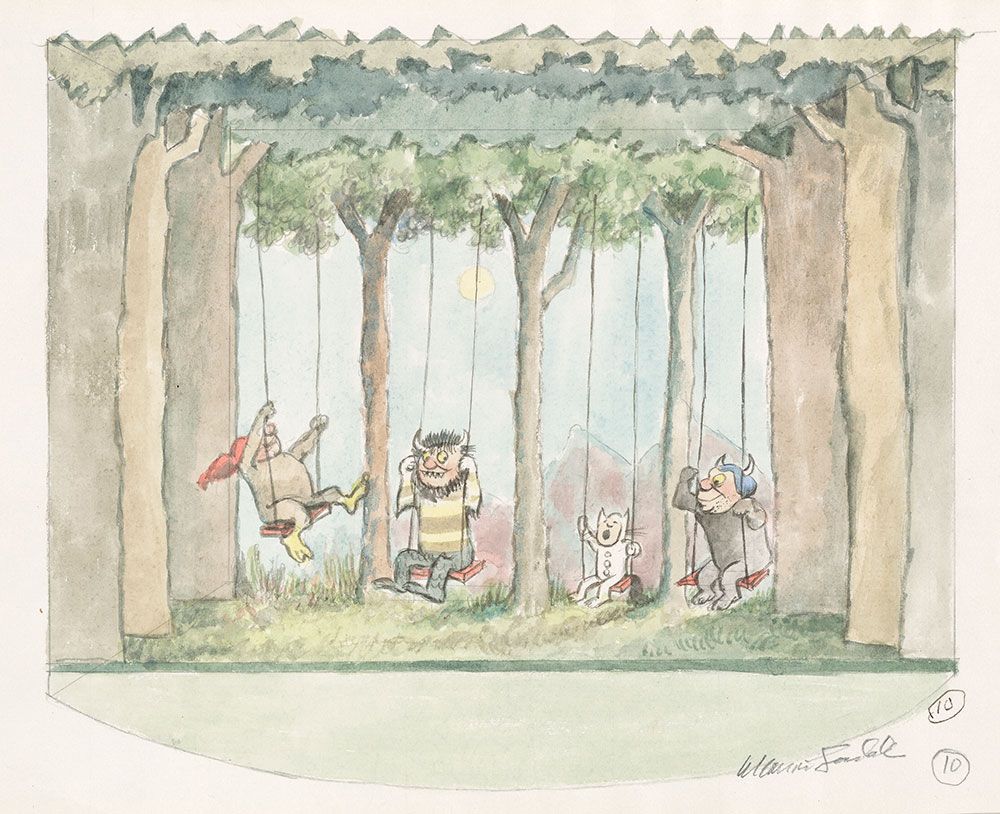

Woolfe describes the resulting set designs as a “flight of Masonic-Pharaonic fancy.” One preliminary design on view in the exhibition, for instance, features a trio of Mozart-esque figures standing in a tropical setting similar to the one depicted in Where the Wild Things Are, flocked on either side by wild animals and Egyptian icons, including a sphinx and a falcon-headed god.

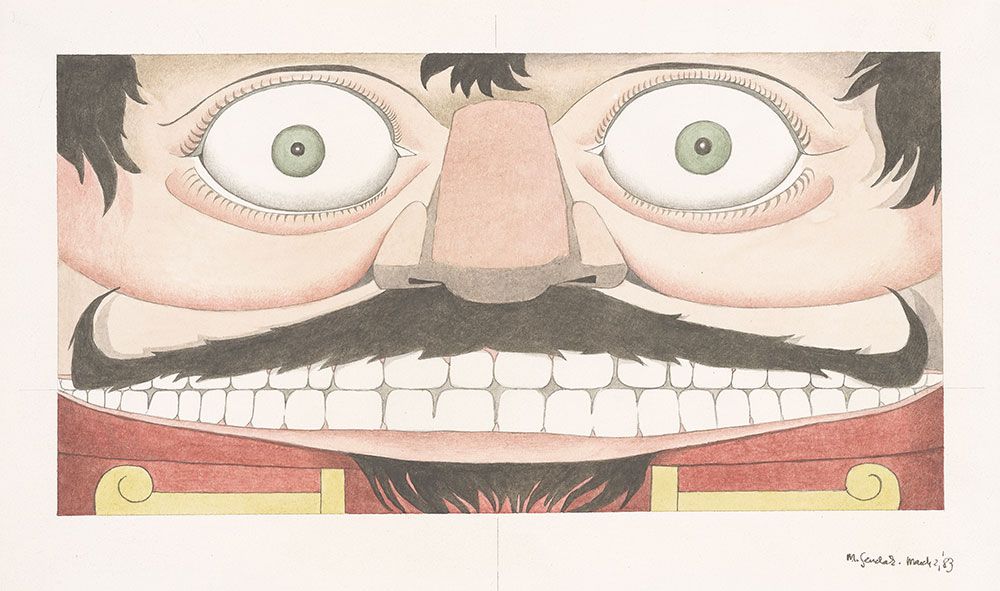

Drawing the Curtain also explores Sendak’s contributions to a darkly subversive adaptation of The Nutcracker, Leoš Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen, Sergei Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges, and his own magnum opus, Where the Wild Things Are. (The operatic adaption of the book, set to music by composer Oliver Knussen, premiered in 1980.)

A number of drawings by 18th- and 19th-century artists who inspired Sendak—particularly William Blake, Giambattista Tiepolo and his son Domenico—are on view alongside his original creations. Drawn from the Morgan’s collection, these images directly influenced the illustrator, who encountered the artists’ work during his many visits to the Manhattan museum. In addition to spotlighting Sendak’s operatic designs and the earlier artists who shaped his distinctive style, the exhibition features costumes and props used in his productions, as well as artifacts on loan from the Maurice Sendak Foundation.

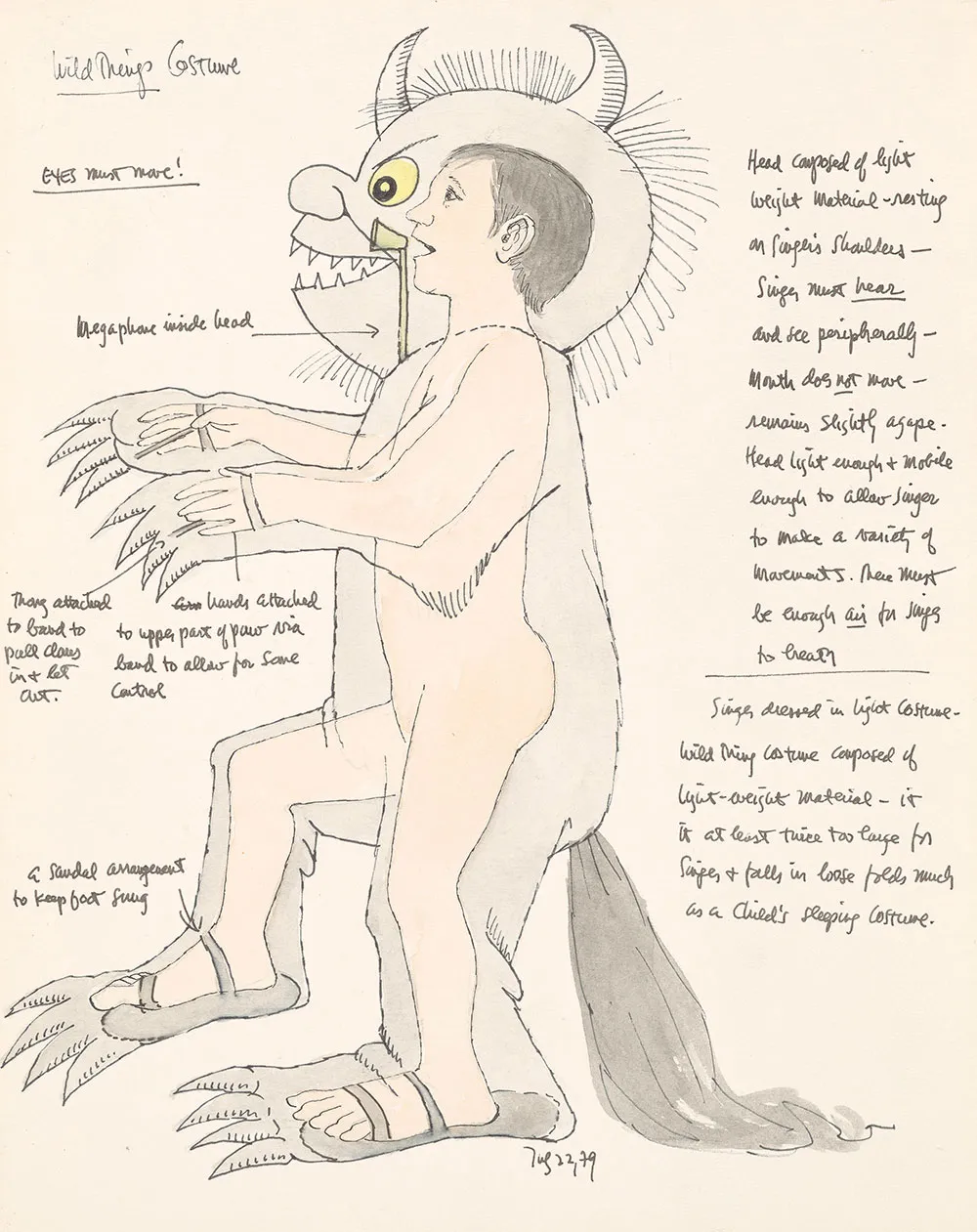

A definite highlight of the Where the Wild Things Are ephemera featured in the show is a watercolor and graphite study of Moishe, one of the beasts encountered by protagonist Max on his mystical journey. As Artsy’s Ludel notes, the drawing finds a young boy wearing a colossal Wild Things costume. (Early versions of the get-up were so cumbersome that performers found themselves unable to breathe, and one actor even fell off of the stage.) Sendak’s notes, ranging from “Eyes must move!” to “megaphone inside head” and “must hear and see peripherally,” pepper the sketch’s margins.

According to the Morgan, the final iteration of the costume, used in a revamped 1984 production of the show, weighed up to 150 pounds and required three individual performers working in tandem: an offstage singer who provided the character’s voice; a puppeteer wearing the suit and controlling its arms, legs and head; and an offstage remote-control operator tasked with making the figure’s eyes move.

These technical details are impressive in their own right, but perhaps the most striking aspect of the sketch is its acknowledgement of the duality inherent in both the theater and Sendak’s oeuvre.

“The boy in the monster, the monster in the boy,” as Woolfe observes for The New York Times. “This is the reality Sendak ... wanted us to see, and understand.”

Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum through October 6.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)