Newly Discovered Indonesian Cave Art May Represent World’s Oldest Known Hunting Scene

The finding bolsters the idea that even 44,000 years ago, artistic ingenuity was shaping cultures across the Eurasian continent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/30/5a302cda-83f4-4286-b6b3-995b6c894637/painting_2.jpg)

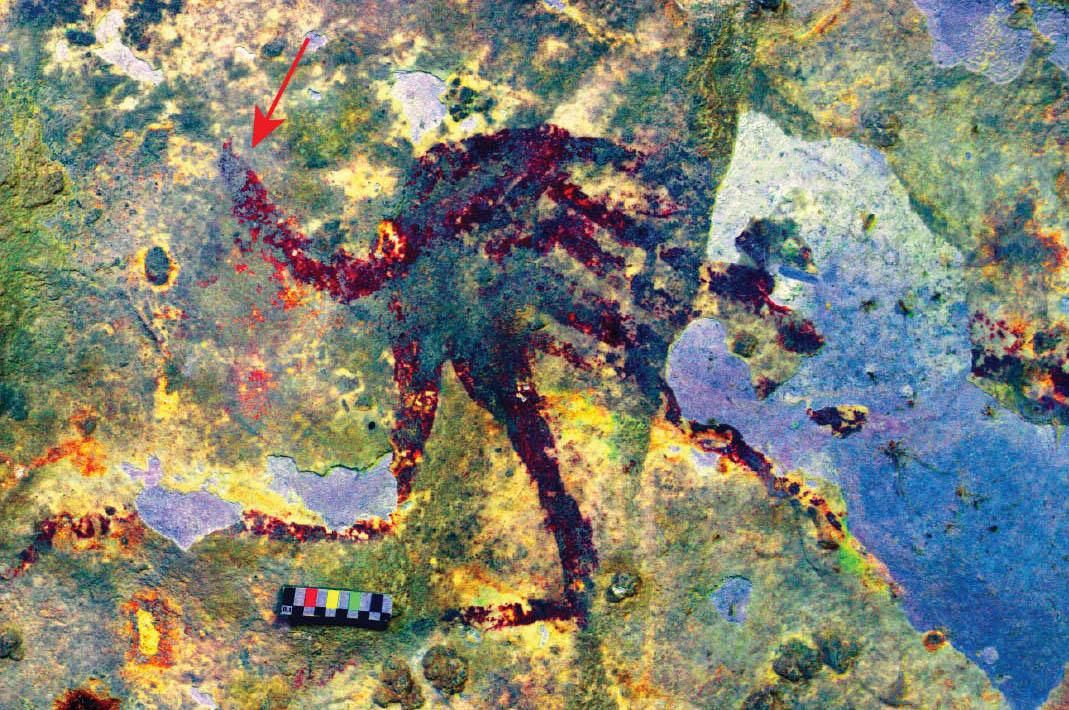

Deep in the bowels of a cave system on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, in a dim chamber accessible only to the most intrepid of spelunkers, lies a red-tinted painting depicting what appears to be a vivid hunt or ritual. In the scene, two wild pigs and four anoas, or dwarf buffaloes, scurry about as their apparent pursuers—mythical, humanoid figures sporting animal features like snouts, beaks and tails—give chase, armed with rope- and spear-like weapons.

Though its pigment is faded and its rocky canvas chipped, the mural is a breathtaking work of art that hints at the sophistication of its creators. And, at an estimated 44,000 years old, the work is poised to help researchers rewrite the history of visual storytelling, according to a study published yesterday in the journal Nature.

If this date is correct, the newly discovered cave painting represents the oldest known example of a story told through art, predating comparable murals previously found in Europe. The findings offer a new understanding of when and where modern humans first acquired the self-awareness and creativity needed to translate life forms and objects from the real world into the abstract.

“We think of the ability for humans to make a story, a narrative scene, as one of the last steps of human cognition,” study author Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist at Griffith University in Australia, tells Michael Price at Science. “This is the oldest rock art in the world and all of the key aspects of modern cognition are there.”

Geographically, the study’s findings aren’t unique: Plenty of other cave art sites have been documented in Indonesia over the past few decades. With each new discovery, archaeologists have increasingly abandoned the long-held assumption that modern human intelligence arose exclusively in Europe—a theory limited more by where researchers were searching for clues, rather than where they actually existed.

“Europe was once thought of as a ‘finishing school’ for humanity, because France in particular was the subject of intense research early on,” University of Victoria archaeologist April Nowell, who wasn’t involved in the study, explains to National Geographic’s Michael Greshko. “We have long known this view … is no longer tenable.”

Findings like these, Nowell adds, “continue to underscore this point.”

What’s emerging instead is a story of parallelism—multiple lines of our ancestors touching on the same cultural themes on opposite sides of the Eurasian continent. (Some researchers have taken this as a hint that these advanced cognitive traits may have been present in a common ancestor in Africa, Price reports, but that has yet to be confirmed.)

One prominent commonality is the artistic blending of human and animal features: In Germany, a 40,000-year-old sculpture depicts a person with a lion’s head; in France, a 14,000- to 21,000-year old mural shows a beaked figure sparring with a bison.

This motif repeats itself in spades in the newest example, found in late 2017 by Indonesian archaeologist Hamrullah. (Like many Indonesians, he uses just one name.) The presumed poachers the painting depicts are what archaeologists call therianthropes, or characters that blur the line between human and animal. Such figures are thought to have otherworldly significance as “spirit helpers,” reports Becky Ferreira at the New York Times.

Still, so far removed from the original rendering, all modern interpretations are subject to skepticism. Though the study authors describe the painting as a “hunting scene,” that might not be the case, points out Sue O’Connor, an archaeologist at Australian National University who was not involved in the study, in an interview with Ferreira.

Instead, she says, it could be about “the relationship between people and animals, or even a shamanic ritual.”

Others, like Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at England’s University of Southampton who also wasn’t involved in the study, are hesitant to stamp the mural with any kind of “oldest” label before all of its characters are definitively dated, according to Ferreira. Aubert and his colleagues examined only the ages of the mural’s animals, chemically analyzing mineral deposits called “cave popcorn” that had formed atop the paint. The human-animal hybrids could have been added at a later date, Pike points out.

With these questions and more left open, the researchers are now racing to find more answers and evidence before the paintings disappear. Though the causes remain unclear, the region’s artworks have begun to rapidly flake off cave walls in recent years, Greshko reports.

The team is now trying to determine what’s behind the deterioration in hopes of stopping it. Though long left behind by its creators, the artwork is a creative through line to our past, Aubert tells Greshko.

“When you do an archaeological excavation, you usually find … their trash,” he says. “But when you look at rock art, it’s not rubbish. It seems like a message. We can feel a connection to it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)