Newly Discovered Swimming Dinosaur Is Delightfully Bizarre

The cartoonish creature blends characteristics of velociraptors, penguins, swans, and ducks

:focal(4488x1659:4489x1660)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/e3/70e3e340-c3a0-4b76-a82d-8b2d158f1406/636481582904343761-duck-dino2.jpg)

The newest fluffy dinosaur discovery is sublimely ridiculous, a mishmash of fierce claws, a graceful neck and ungainly arms. Meet Halszkaraptor.

For paleontologists, discovering the creature was likely akin to 18th-century natural historians finding platypus: they were blown over in disbelief. The blend of velociraptor and duck is so bizarre scientists originally thought it was an obvious fake. But they were delighted to find it wasn't, describing the find this week in Nature.

Even the 70-million year-old fossil’s journey to discovery is strange. The fossil was smuggled out of Mongolia and moved around the black market fossil trade bouncing from Japan to Britain to France, reports Ed Yong for The Atlantic. That’s when François Escuillié heard rumours of the unusual fossil.

Escuillié, a private fossil collector, had just rescued a collection of poached fossils and returned them to Mongolia, reports Michael Greshko for National Geographic. He took the chance that Halszkaraptor was a real creature and not a hoax, buying it and delivering it to Pascal Godefroit for assessment.

Godefroit and his team originally thought the fossil was a chimera, a concoction of different fossils glued together to create an imaginary beast, Yong reports. Its toes bore curving velociraptor-like claws, while its forelimbs were an odd hybrid of the usual raptor limbs and more penguin-like flippers. Between its strange features and sketchy history, they suspected it was a poorly-constructed fossil. But if it was real, they concluded, it must be a raptor adapted to swimming—the first true dinosaur to join the seas with reptilian plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs.

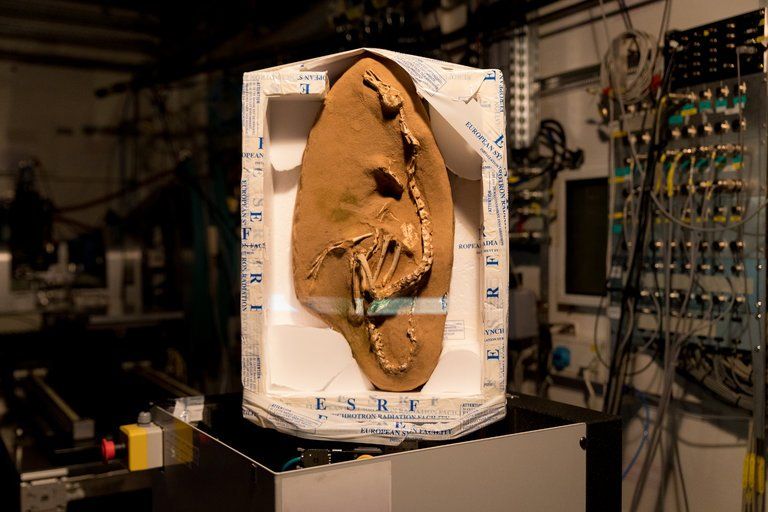

But the fossil was still partially-encased in solid rock. So Godefroit and his team brought the rock to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility to peer at the mineralized bones still locked inside using the particle accelerator. “They said ‘convince me it’s a fake,’” the facility’s paleontologist Vincent Fernandez tells the New York Times. “I thought it would be very obvious. But I looked at it for hours and hours and I couldn’t find anything.”

They found more of the same bizarre mix—pieces of the swan-like neck and duck snout were encased alongside the stubby-paddle arms, confirming the creature was real.

The new creature’s name—Halszkaraptor escuilliei—honors Escuillié for his role in discovering the fossil, and is a tribute to the Polish paleontologist Halszka Osmólska responsible for discovering at least a dozen Mongolian dinosaurs, Yong reports. Once the fossil was substantiated, Escuillié got to work on repatriating it to Mongolia as soon as Godefroit and his team finish studying it in Belgium.

Halszkaraptor is the latest of the theropods; its taxonomic siblings including the iconic Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor. Like its mostly meat-eating kin, it appears to be a predator, but unlike them it is the first theropod suited to a life hunting in the seas.

Its duck-like snout was threaded with channels to carry nerves and blood vessels, reports Greshko. This would boost sensitivity the same way we see in modern crocodiles and aquatic birds. Its bill jammed full of tiny teeth perfect for grabbing fish suggest Halszkaraptor specialized in diving after ancient sea creatures for its mealtimes, a long-extinct version of the modern cormorant. Its long neck is streamlined for swimming, smashing sideways into prey, or darting down to nab fish in a precursor of the heron’s fishing strategy.

But story of how Halszkaraptor came to be is far from clear. The strong hindlimbs allowed it to walk on land with ease, reports Greshko, allowing it to still return to land to lay its eggs. Those same powerful legs could also provide a strong kick while swimming underwater, but with sharp claws instead of webbed toes their hindlimbs were likely better suited to running. And while the elongated and flattened bones match the proportion of swimming birds, Yong points out Godefroit and his team aren’t yet convinced they served as flippers for the usual creature. Until scientists understand how the limbs joined at the shoulders, they don’t know if they could be moved propulsively like a penguin, or if their utility is another strange quirk yet to be unravelled.

For all the mysteries that remain, one thing is clear. Someday soon, someone is going to name this awkward sharp-toothed swan as their favorite dinosaur.

Editor's Note 12/8/2017: The age of the dinosaur was initially incorrect; the creature is around 70 million years old.