North America’s Trees Create Some of the World’s Hottest Forest Fires

What makes certain forest fires especially destructive?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/ae/6baea264-39a2-4fe3-816b-11d8f8697fda/forest_fire_42-15314357.jpg)

The northern reaches of Eurasia and North America are quite similar—both home to a nearly continuous belt of boreal forest. But forest fires burning in the upper tiers of the U.S. and Canada tend to be more intense and destructive than those burning across the North Pole, in Russia and parts of Scandinavia. One team of scientists wondered why—and set out to find an answer by using computer models, ground observation and about 10 years of satellite data.

As Ria Misra at io9 writes, the researchers found that the difference is primarily due to the species of trees that tend to thrive on our continent. (They recently published their findings in the journal Nature Geoscience.) NASA’s Earth Observatory explains:

In North America, the dominant tree species tend to be “fire embracers.” That is, the life cycles of the forests have evolved to sustain nearly complete burns (crown fires) and to quickly re-colonize an area after a fire. North American forests tend to have more black spruce, white spruce, and jack pine—species with branches lower to the ground, thinner bark, and pine cones that open up after being burned by fire. On the other hand, Eurasian forests have more species that resist fire with thicker bark, moister needles, and fewer low-hanging branches.

The study’s lead author, Brendan Rogers, further explains that “adaptations to surviving in fire-prone environments have resulted in very different fire regimes between the continents.”

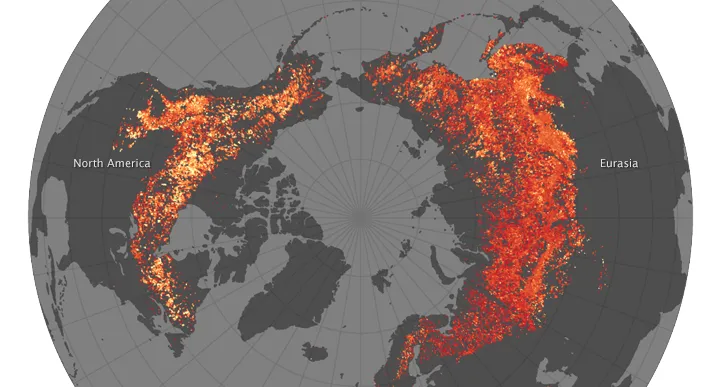

NASA’s Earth Observatory has this cool graphic showing the higher fire radiative power generated by North America’s forest fires as compared to fires in Eurasia, which are less intense, overall. The lighter, more yellow areas represent more intense fires:

The researchers also evaluated just what kind of impact forest fires burning on either continent have on Earth’s climate. Surprisingly, they established that the smokier, hotter and bigger North American fires—found to destroy around 35 percent more vegetation than their Eurasian counterparts—may actually help cool the climate in the first ten years after the blaze. The University of California, Irvine, explains:

The loss of leaves and branches from North American blazes exposes underlying snow and allows more sunlight to be reflected in spring months. This has a cooling effect on the climate. In Eurasian forests where tree cover remains relatively intact, this effect is much smaller. The overall impact of forest fires - including atmospheric warming from the released carbon dioxide - is thought to be neutral or warming.

The next step, the scientists say, is to better understand how differences in forest composition may interact with other environmental changes connected to Earth's overall warming. They also hope that their research is factored in to future studies on climate change and forest fire control.

“We need to move beyond generic representations of trees, and use this information to make informed decisions on how to manage forest fires for climate mitigation,” Rogers told the Woods Hole Research Center.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)