Notebook of Poetry Penned by Bonnie and Clyde Set to Go on Auction

The volume features poems written by the outlaw duo during their Depression-era crime spree

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/82/db82b8dd-7a83-40d2-b8a9-376c3606ea2d/bonnie_and_clyde.jpeg)

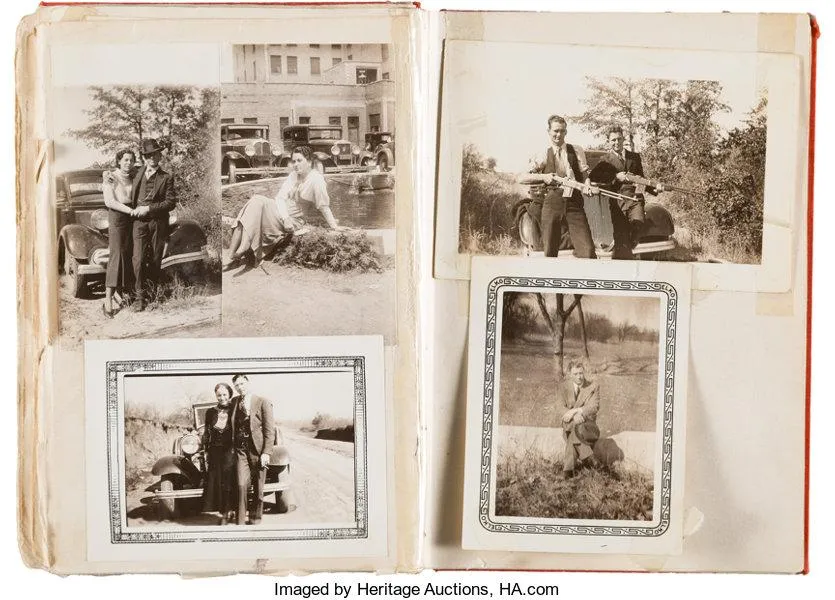

Bonnie Parker’s poetry has long provided a portal into the fleeting lives of Depression-era America’s most notorious pair of outlaws. But as Alison Flood reports for the Guardian, a newly revealed notebook once owned by the couple suggests Parker wasn’t the only one to try her hand at creative writing. The volume, set to go on auction this April alongside a trove of photographs, includes a poem ostensibly written in Clyde Barrow’s spelling error-filled scrawl.

According to Atlas Obscura’s Matthew Taub, the notebook itself is a “Year Book,” or day planner, dating to 1933. It’s unclear exactly how the diary ended up in Parker and Barrow’s possession—Heritage Auctions writes that it was “apparently discarded”—but penciled-in entries point toward the original owner’s occupation as a dedicated, perhaps even professional, golf player. Whatever the planner’s provenance, Taub notes that the duo soon converted it into a poetry workbook.

A complete draft of Parker’s best-known poem, a 16-stanza work alternately titled “The Trail’s End” or “The Story of Bonnie and Clyde,” was originally written in the notebook, but it was later ripped out and stored in an envelope labeled “Bonnie & Clyde. Written by Bonnie.” Still, miscellaneous verses from the poem remain scattered throughout the volume.

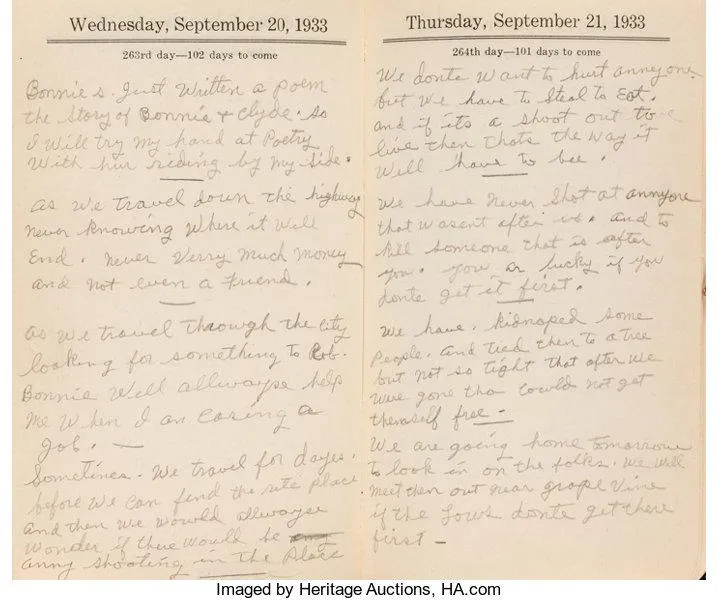

Interestingly, the Guardian’s Flood explains, a 13-stanza poem penned by Barrow appears to serve as a direct response to Parker’s work, opening with the lines: “Bonnie s Just Written a poem / the Story of Bonnie & Clyde. So / I will try my hand at Poetry / With her riding by my side.” (This language is taken directly from Heritage Auction’s listing, which further states that the lines attributed to Barrow are filled with “gangster-ese” jargon and reflective of his minimal education.)

Much like Parker’s poetry, Barrow’s writing attempts to refute the media’s depiction of the pair as ruthless, cold-blooded killers. Whereas Parker observes that “If they try to act like citizens / and rent them a nice little flat. / About the third night; / they’re invited to fight, / by a sub-gun’s rat-tat-tat,” Barrow argues, “We donte want to hurt anney one / but we have to Steal to eat. / and if it’s a shoot out to / to live that’s the way it / will have to bee.”

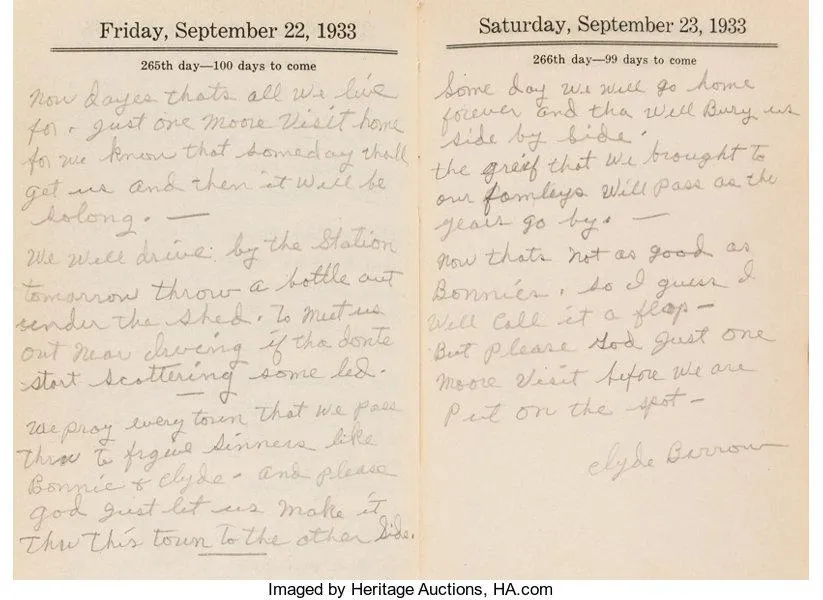

At the same time, Atlas Obscura’s Taub writes, the two were quick to acknowledge the probable denouement of their decidedly law-unabiding lifestyle. In his untitled work, Barrow notes, “We are going home tomorrow / to look in on the folks. We will / meet then out near Grape Vine / if the Laws donte get there / first.” He finishes the poem with a plaintive plea: “But please God Just one / moore visit before we are / Put on the spot.”

Parker describes the pair’s likely fate in more artful terms, concluding “The Trail’s End” with a prescient prediction: “Some day they’ll go down together / they’ll bury them side by side. / To few it’ll be grief, / to the law a relief / but it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.”

Soon after Parker wrote these lines, she and Barrow were ambushed by police, who, according to a contemporary New York Times account, “riddled them and their car with a deadly hail of bullets.” Parker’s grief-stricken mother refused to allow the couple to be buried together, preventing at least one aspect of the poem from coming to fruition.

Still, Heritage Auctions points out, the elder Parker didn’t completely ignore her daughter’s unusual legacy. Working with Barrow’s sister Nell, she produced a history of the couple titled Fugitives: The Story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. Rather than celebrating the pair’s exploits, however, the biography strove to reveal the harsh realities of life on the run. As the co-authors wrote in the book’s foreword, “We feel that their life story, as set down here, is the greatest indictment known to modern times against a life of crime.”

They continued, “The two years which Bonnie and Clyde spent as fugitives, hunted by officers from all over the Southwest, were the most horrible years ever spent by two young people.”

After Nell’s death, the poetry workbook she’d inherited following her brother’s death was passed down to her son—Barrow’s nephew. He eventually decided to consign the journal, as well as an archive filled with rare photographs of the outlaw couple, to auction.

Speaking to the Mirror’s Christopher Bucktin, auctioneer Don Ackerman concludes, “The poems are a window on the mindset of criminals hunted down, not knowing which day would be their last. They knew they were doomed.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)