NYC Pop-Up Exhibition Traces Broken Windows Policing’s Toll

The show explores how the policing of minor crimes has caused an uptick in racial profiling, particularly targeting African American and Latino communities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/fb/99fbb223-0152-40d8-af60-d71ee1c073eb/the_talk_michael_dantuono.jpg)

“Broken windows” policing is a criminological theory that suggests a series of unpunished minor crimes, as represented by the eponymous broken window, eventually spirals into a cascade of more serious violent crime.

Social scientists George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson first outlined the broken windows theory in a 1982 Atlantic article, but the targeted policing it advocates wasn’t widely adopted until 1994, when New York City’s mayor Rudy Giuliani pledged to “clean up” the city.

As Sarah Cascone reports for artnet News, the roughly 60 works featured in Manhattan’s latest pop-up exhibition—the New York Civil Liberties Union’s Museum of Broken Windows—use art, archival photographs and newspaper articles to chronicle the toll of that policy, particularly on African American and Latino communities.

“Broken windows policing … has turned neighborhoods into occupation zones,” NYCLU advocacy director Johanna Miller said in a statement. “The goal of the Museum is to bring the emotional, physical and societal impacts of this style of policing to life for all New Yorkers, and elevate a critical conversation about what it means to be and feel safe in this city.”

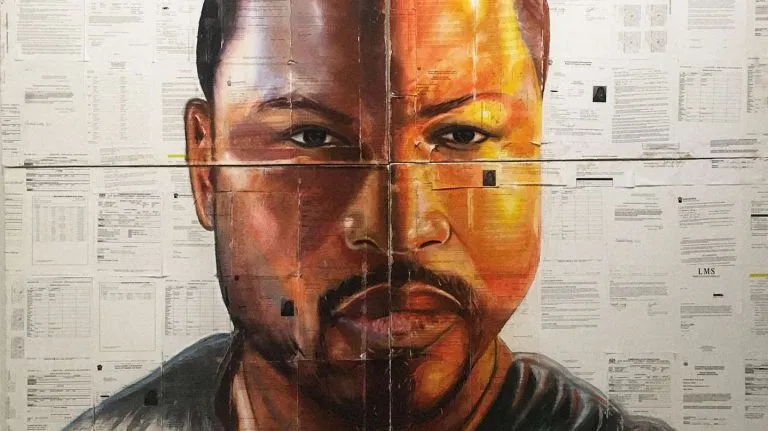

Many of the individuals featured in the pop-up exhibition have been personally affected by these policing strategies, Nadja Sayej writes for the Guardian. Philadelphia artist Russell Craig spent seven years imprisoned for non-violent drug offenses, and upon his release in 2013, crafted a piercing self-portrait on a canvas covered in court documents pertaining to his case. Jesse Krimes, another formerly incarcerated artist, used hair gel and a plastic spoon to transfer ink from copies of the New York Times onto his bedsheets.

These works, which artnet’s Cascone explains were smuggled out of prison by Krimes’ girlfriend, stand alongside contributions from artists including Dread Scott, Hank Willis Thomas, Molly Crabapple and Sam Durant. Scott’s piece, a stark black banner, is emblazoned with the words “A man was lynched by police yesterday.” Crabapple’s animated short, entitled “Broken Windows,” explores the death of Staten Islander Eric Garner at the hands of a New York Police Department officer.

Garner’s story, and those of other victims of police violence, are a recurring theme throughout the show. Nafis M. White’s “Phantom Negro Weapons” series presents minimalist photographs of items held by unarmed African Americans stopped by police. Without context, the collection of objects referenced in the rest of White’s photographs appear mundane: A handful of change, a wallet and keys, and a can of Arizona green tea all make the cut, as do several empty shots that truly exemplify the “phantom” nature of the weapons imagined by arresting officers. But for those who know the stories behind these objects, the selections are supercharged, with a spilled bag of Skittles instantly summoning the memory of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old shot by neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman, who was later acquitted of any crime, in February 2012.

“What case after case has proved is that the suspect, then police shooting victim, often has nothing more in their possession than their wallet, their clothing, a cell phone, a spoon, some candy or in many cases, nothing at all,” White writes on her website.

A new series commissioned specifically for the exhibit features Tracy Hetzel’s watercolor portraits of mothers holding picture of their sons, all of whom were killed by the NYPD. As curator Daveen Trentman tells Cascone, these bereaved family members form a “sorority that nobody wants to be in” and have been vocal advocates of police reform.

Michael D’Antuono’s “The Talk” perhaps best encapsulates the show’s message. The 2015 painting finds a young African American boy seated on a couch across from his mother and father, who are attempting to describe the tale playing out on a television nearby. On the screen, a news ticker proclaims, “No indictment in police shooting of unarmed youth.” Below these words flash images of a white policeman and an African American boy whose bright orange hoodie mirrors that of the child seated on the couch.

The Museum of Broken Windows’ nine-day run is accompanied by a series of talks dedicated to the issues touched on in the show. Scheduled events include “Ending the School to Prison Pipeline,” which discusses hopes of ending police involvement in school disciplinary matters, and “Ending the Police Secrecy Law,” which focuses on the impact of a New York law that protects police misconduct records.

“Through art, we will uplift the movement of people who continue to seek justice," Trentman said in a statement.

The Museum of Broken Windows is on view at 9 W. 8th Street, New York City, through September 30. Admission is free.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)