Oklahoma Has Way Too Many Storm Chasers, And Most of Them Aren’t Doing Much Good

During a huge tornado hundreds of storm chasers will clog the roads trying to catch a view

In the past two weeks, Oklahoma has seen two massive tornadoes: the Moore tornado and the more recent El Reno tornado, both powerful EF-5 storms that were responsible for many deaths. Saturating the discussion around both storms was a bevy of dramatic close-up footage of the tornadoes as they tore through the landscape. Some of this footage was captured by news agencies and professional storm chasers, but much of it came from amateurs.

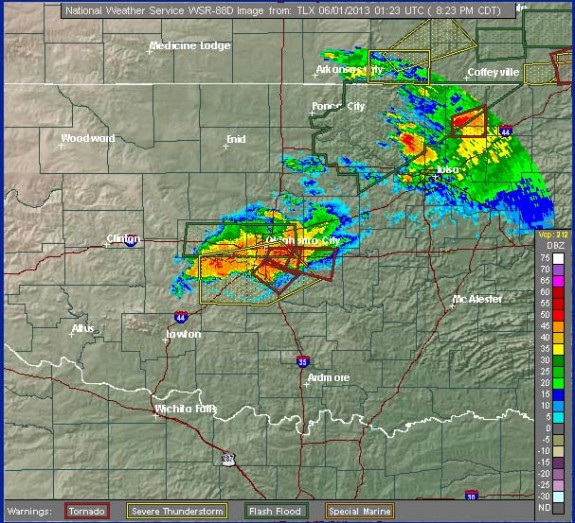

During the May 31 El Reno tornado, says National Geographic, when the National Weather Service was calling for people to take shelter, “at least 60 storm chasers stayed on the roads, heading directly toward the tornado itself. Radar imaging posted on Twitter Friday night shows that as the deadly El Reno twister touched down, several cars were precariously close to the tornado core.”

Four storm chasers died during that tornado, three of them experienced veterans, and three others had a close call when their car was tossed 600 feet.

The deaths have sparked a debate over the sensibility and usefulness of what many are describing as a notable increase in recent years of the number of people who are out there chasing storms.

The rise in popularity of storm chasing, said Tim Samaras, who died during the May 31 tornado, to National Geographic, has led to dangerous overcrowding near a big storm.

“We run into all the time,” he said. “On a big tornado day in Oklahoma, you can have hundreds of storm chasers lined up down the road … We know ahead of time when we chase in Oklahoma, there’s going to be a traffic jam.”

That huge number of people on the roads, says Fox, is making an already dangerous situation even worse:

here are too many people with a cell phone in-hand, simply calling themselves “storm chasers.” They clog roads and endanger legitimate researchers like the three who were killed Friday.

“We’ve known now for four or five years that the congestion has gotten so bad, you don’t have escape routes anymore,” Denzer told FOX 13. “You can’t get away.”

To put the risks of storm chasing in context, you need to think about two things: what a storm chasers’ purpose is and what it takes to achieve that goal. Storm chasers generally fall into two camps: those doing or contributing to scientific research, and those trying to capture video or images for media or news purposes. Well, maybe there’s a third camp: those there to gawk.

“You’ve got the group that are basically thrill seekers. They want to get their videos on YouTube. They want to be tweeted,” Dellegatto said.

Meteorologist and former storm chaser Dan Satterfield writes that the risks people are facing to capture all this footage of a storm are, from a scientific standpoint, unnecessary. Trained storm chasers are extremely useful for helping us understand tornadoes. They capture footage that can help researchers test or confirm their theories over how tornadoes work, and they provide on-the-ground confirmation for what weather forecasters are seeing in radar or satellite views. But to do that kind of work, you don’t need to put yourself in harm’s way.

The news media is overplaying the scientific benefit provided by nearly all of these chasers. Especially the silly ones taking armored vehicles on purpose into a tornado. That may make good TV on The Weather Channel, but it’s of no real scientific benefit. If you want to add to the science, take some calculus and enroll at

I’m sure Howie Bluestein can still fill a board full of equations to help you understand the real science! Dr. Bluestein measured the highest winds ever recorded on the planet in May 1999 during the first Moore Tornado. He did it from a mile away using a Doppler radar, not a ridiculous looking armored SUV.

There’s also the question of whether the news footage of a tornado is useful, but that’s a different discussion. Here Satterfield wants to point something else out:

I know of NO ONE who makes a real living storm chasing. No one. I do know quite a few meteorologists who make a decent living trying to figure out how these storms develop and how to forecast them better. They had to learn some physics and maths to do that.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)