Medieval Manuscript Returns to Ireland After Hundreds of Years in British Hands

The 15th-century Book of Lismore features the only surviving Irish translation of Marco Polo’s travels, among other historical texts

:focal(664x402:665x403)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/32/c332f2e8-eee8-48f8-8f41-96a35dff2ef0/the_book_of_lismore_at_university_college_cork.jpg)

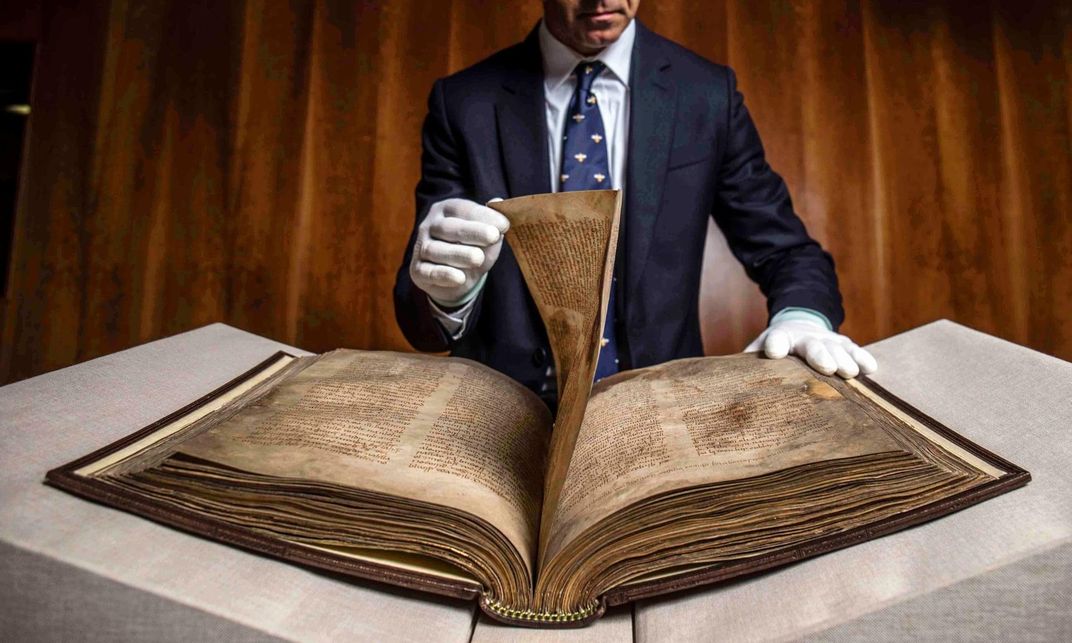

One of Ireland’s most valuable medieval manuscripts, the Book of Lismore, has returned home nearly four centuries after its seizure from Kilbrittain Castle in County Cork.

The text’s previous owner, the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, donated the historic volume—which changed hands multiple times following its capture at Kilbrittain in the early 1640s—to the University College Cork’s (UCC) Boole Library.

As UCC notes in a statement, the collection of 198 vellum folios is considered one of the “great books” of Ireland. Created for the Irish Lord of Carbery, Fínghin Mac Carthaigh Riabhach, and his wife, Caitilín, in the late 15th century, the manuscript contains a number of rare medieval Irish texts and translations of European stories, as well as the only surviving Irish translation of the travels of Marco Polo.

According to Gareth Harris of the Art Newspaper, the book also includes accounts of the lives of Irish saints and secular tales such as Agallamh na Seanórach, a lengthy medieval Irish poem that centers on the legendary hero Fionn mac Cumhaill and his Fianna warriors.

In an opinion piece for Irish broadcaster RTÉ, Pádraig Ó Macháin, an expert on Modern Irish at UCC, argues that the selection of stories featured in the manuscript makes “a self-assured statement about aristocratic literary taste in autonomous Gaelic Ireland in the late 15th century.”

He adds, “The geographical area in which the Book was written ... was a thriving center of intellectual activity. The seaboard of west Cork was a focal point for poets and for scholars of other disciplines such as medicine and history. ... There was also an active interest here in the translation of works popular at the time in mainland Europe.”

After its removal from Kilbrittain in the 17th century, the Book of Lismore came into the possession of the first Irish Earl of Cork, Richard Boyle, who was then living at Lismore Castle in County Waterford. The following century, ownership of the castle transferred through marriage from the Boyle family to the English Cavendishes, Dukes of Devonshire; the precious artifact was subsequently stowed away inside Lismore’s walls—possibly for safekeeping. The tome was only rediscovered in 1814, when renovations ordered by the sixth Duke of Devonshire were underway.

Per the statement, the book was housed mainly at Lismore until 1914, when it was transferred to Devonshire House in London. Later, the Cavendish family moved the manuscript to their ancestral seat of Chatsworth in Derbyshire. It remained there until its recent donation to UCC.

John O’Halloran, the university’s interim president, describes the Book of Lismore as a “vital symbol of our cultural heritage.”

In the statement, he adds, “This extraordinary act of generosity by the Duke of Devonshire reaffirms the shared understanding between our respective countries and cultures, an understanding that is based on enlightenment, civility and common purpose.”

UCC plans to develop a Treasures Gallery to display the book to the public. Ó Macháin writes that staff also hope to work with students to transcribe the Irish text and make it openly accessible through the university’s online portal. Both undergraduate and graduate students will have opportunities to study the text firsthand, he notes for RTÉ.

In a separate statement, the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, who have owned the book since their organization’s establishment in 1946, note that talks about repatriating the manuscript have been ongoing for about a decade.

“Ever since the Book of Lismore was loaned to University College Cork for an exhibition in 2011, we have been considering ways for it to return there permanently,” says Peregrine Cavendish, 12th Duke of Devonshire, in the Trustees’ statement. “My family and I are delighted this has been possible, and hope that it will benefit many generations of students, scholars and visitors to the university.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)