Pioneering Victorian Suffragist’s Unseen Watercolor Paintings Are Up for Sale

Seven landscape scenes by 19th-century British social reformer Josephine Butler are headed to the auction block

:focal(1970x1219:1971x1220)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/03/bd03eafa-d165-407e-83b8-5090dbf95336/15337_3_1.jpeg)

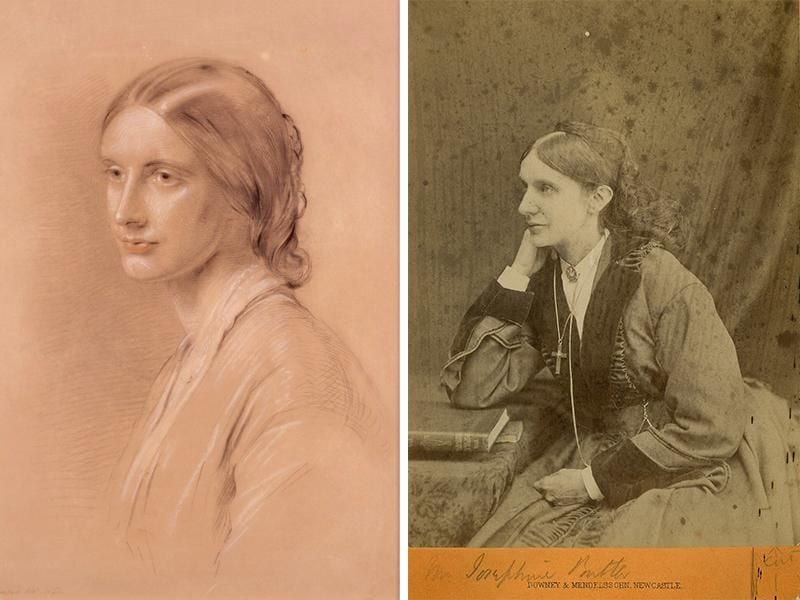

Josephine Butler is best known as an influential women’s rights activist and social justice reformer. But the 19th-century British feminist, who campaigned against the slave trade and the mistreatment of sex workers, among other injustices, had another hidden talent, too: painting.

As Maev Kennedy reports for the Art Newspaper, Ewbank’s Auctions in Surrey, England, is set to offer seven of Butler’s watercolor paintings in an online sale today, March 25.

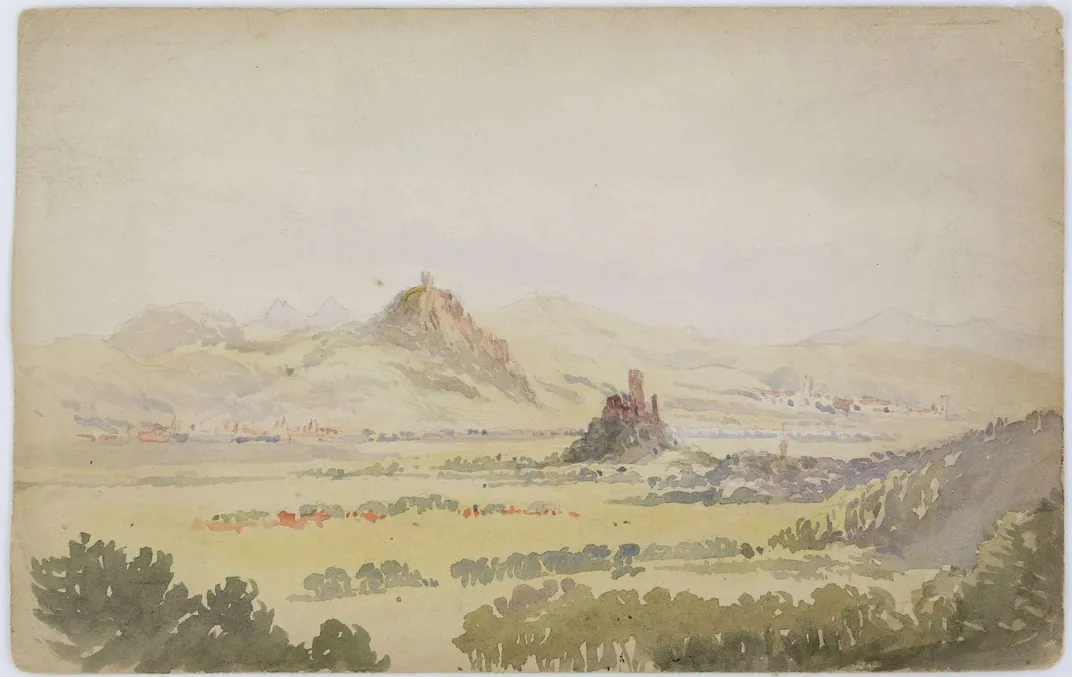

Per Roland Arkell of the Antiques Trade Gazette, the landscape scenes—inspired by the Victorian activist’s European travels—are expected to sell for around £150 to £250 each (roughly $200 to $340).

“[W]e take them out occasionally to look at them, but I felt the time had come for them to go either to an appreciative collector or to a public institution that would put them on display,” says Jonathan Withers, Butler’s great-great-great nephew and the works’ current owner, in a statement. “They really are very beautiful and accomplished.”

One painting, A Puzzle Monkey Pine Tree in Edith Leopold's Garden Milside Genoa, features a quaint image of a coniferous tree on the side of a paved walkway in the Italian city. Though foliage and a tiny building are visible in the distance, the delicately rendered leaves of the eponymous tree are by far the piece’s most noticeable features.

Another work in the auction, The Lieben Geberge, From the Terrace at Bonn, shows a hazy view of a walkway near a river. Blue-gray mountains—the Siebengebire, or Seven Hills, of Bonn—loom in the distance.

The seven sketches are undated but likely span several trips made between 1864 and 1889, according to the statement. Butler’s handwritten notes on the backs of the paintings indicate that sites depicted include Antibes, a coastal city in southeastern France, and Ahrweiler, a German district bordered to the east by the Rhine.

Born in Northumberland in 1828, Butler belonged to a wealthy family. Her parents treated their children equally, tutoring Butler and her siblings in history and politics and introducing them to prominent members of English society, as Alyssa Atwell writes for UNC-Chapel Hill’s Towards Emancipation? Women in Modern European History digital encyclopedia; these experiences had a profound influence on Butler, informing much of her later activist work.

In 1852, the reformer married George Butler, a scholar and cleric “who shared her hatred of social injustice,” according to English Heritage. The young couple had four children, two of whom died at an early age.

To cope with her grief over these losses, Butler began pursuing charity work. Among other activist endeavors, she fought for the rights of sex workers, campaigned for women’s education and advocated for Parliament to raise the age of consent from 13 to 16, notes the BBC.

In one of her most significant social campaigns, Butler worked to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts, which allowed law enforcement officials to detain women believed to be prostitutes and forcibly examine them for evidence of venereal disease. These efforts proved successful, with the legislation suspended in 1883 and repealed in 1886.

Butler died in 1906, at the age of 78. Though she was primarily known as a pioneering reformer, she enjoyed creating art in her free time, painting watercolors during “much-needed breaks she took to recuperate from illness and depression,” per the statement.

Most of these pieces have remained in Butler’s family, unseen by the public, since her death. The activist’s grandson gifted the seven currently up for sale to Withers at his christening nearly 60 years ago; he’s kept most of them in their original envelope ever since, reports the Art Newspaper.

“[The paintings] show an excellent grasp of perspective, a fine eye for composition and spirited understanding of landscape,” says Ewbank’s partner and specialist Andrew Delve in the statement. “They would grace any collection, but it would be especially pleasing to see them go on public display as a reminder of the remarkable woman behind them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)