Why Pantone’s Color of the Year Is the Shade of Science

PANTONE 18-3838 Ultra Violet is a deep saturated purple, but it doesn’t hold a candle to true ultraviolet

Feeling fatigued by millennial pink? Get ready for a rich, saturated purple with blue undertones to color in your 2018.

That’s right, the folks at Pantone Color Institute have crowned the latest color of the year. According to a press release issued last week, PANTONE 18-3838 Ultra Violet, inspires “originality, ingenuity, and visionary thinking that points us toward the future.”

If that’s not enough, the shade is also said to embody “the mysteries of the cosmos, the intrigue of what lies ahead, and the discoveries beyond where we are now.”

That’s a tall order, but the copy actually aligns with the scientific characteristics of the shade’s namesake, ultraviolet light.

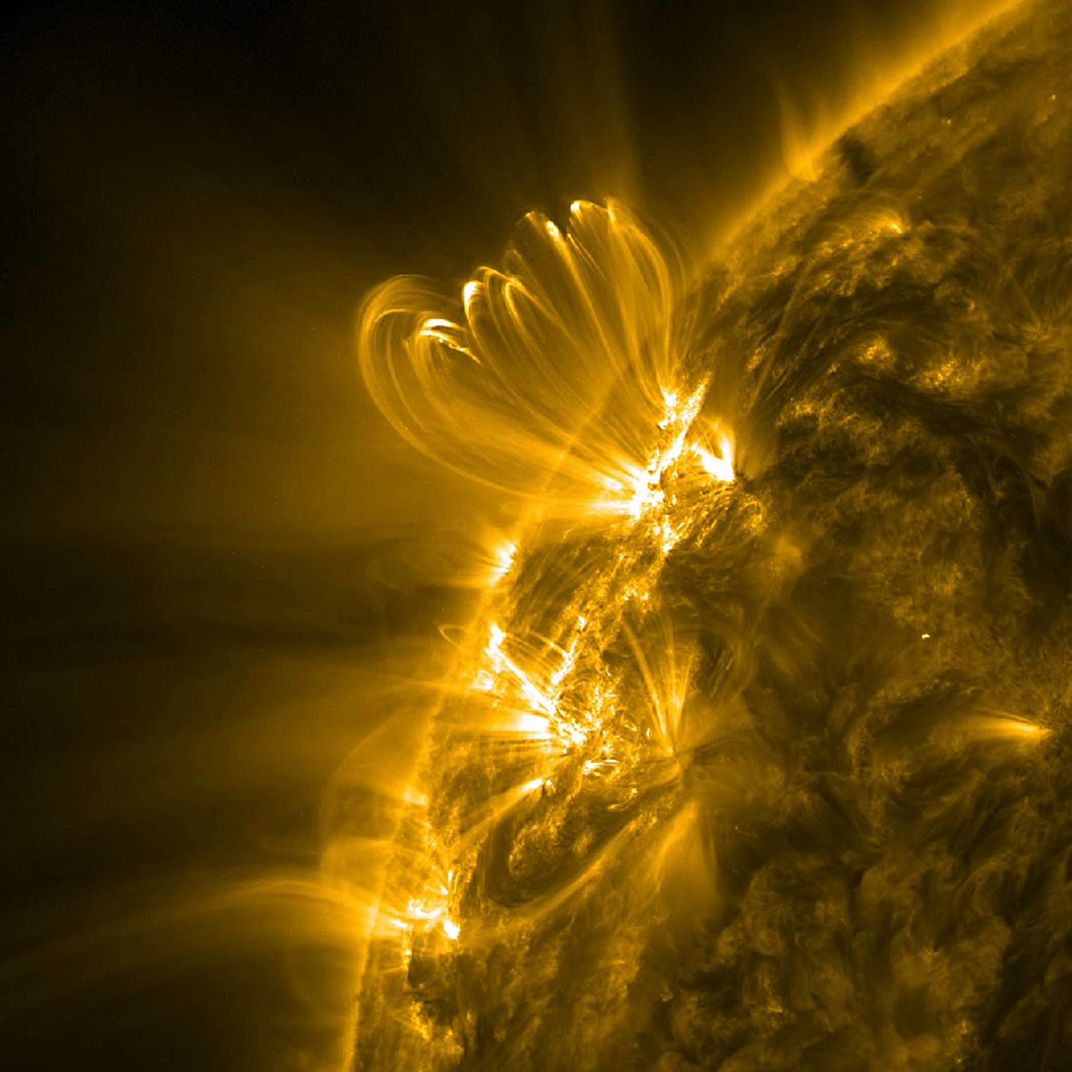

Ultraviolet light makes up about 10 percent of the Sun’s rays, although much of it is filtered by ozone in our atmosphere or scattered by clouds and aerosols. The light that does reach the surface may be invisible to all but a few animals (and a select few humans, which we'll get to later), but you can still see its impact when your skin gets sunburned or you experience snow blindness.

Of course, as Eileen Guo points out over at Inverse, Pantone’s deep purple, isn’t a true ultraviolet. Because the wavelength of light bearing that name is just outside of the visible spectrum, it isn’t an achievable shade even for Pantone’s impressive arsenal of colors.

That being said, black light allows us to enjoy ultraviolet light despite its invisibility, as the high-energy wavelengths trigger fluoresce. Things that glow under blacklight range from the mundane—tonic water, tooth whiteners, and laundry detergent— to the more exotic—making plant chlorophyll appear blood-red, highlighting scorpions in eerie cyan blues and greens, and revealing the otherwise-hidden Blaschko's Lines that stripe humans.

Photographers have long-known about this second-hand ultraviolet light. As Don Komarechka explains in PetaPixel, altering cameras to capture ultraviolet light directly can make for stunning peeks into an otherwise-invisible world. There are also a select few individuals who can also see in ultraviolet. As Michael Zhang notes in a separate article for PetaPixel, those with a condition known as aphakia—eyes that do not have lenses from birth, disease, or surgery—have the ability to make it out (though having one’s lens surgically removed doesn’t exactly seem like a fair trade off unless it's for medically expedient reasons).

As Zhang writes, one of the most famous individuals to have aphakia is none other than Claude Monet. After surgically removing his lenses to combat cataracts at age 82, the French Impressionist began painting the ultraviolet patterns he saw on flowers. “When most people look at water lily flowers, they appear white,” Carl Zimmer observes for Download the Universe. “After his cataract surgery, Monet's blue-tuned pigments could grab some of the UV light bouncing off of the petals. He started to paint the flowers a whitish-blue.”

Unlike the royal look of Pantone’s 2018 selection, a true ultraviolet light looks more like a whitish blue or violet, according to those with the condition. As Hambling explains, “This appears to be because the three types of colour receptor (red, green and blue) have similar sensitivity to ultraviolet, so it comes out as a mixture of all three — basically white, but slightly blue because the blue sensors are somewhat better at picking up UV.”