This Parasitic Worm Is Thriving in Nature, but May Affect Your Sushi Dinner

The worms are 283-times more abundant than they were in the 1970s, which might be a sign of healthy marine ecosystems

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/ac/32ac1313-13e2-467d-bffd-87b08944307c/7775016966_4ffef62af5_b.jpg)

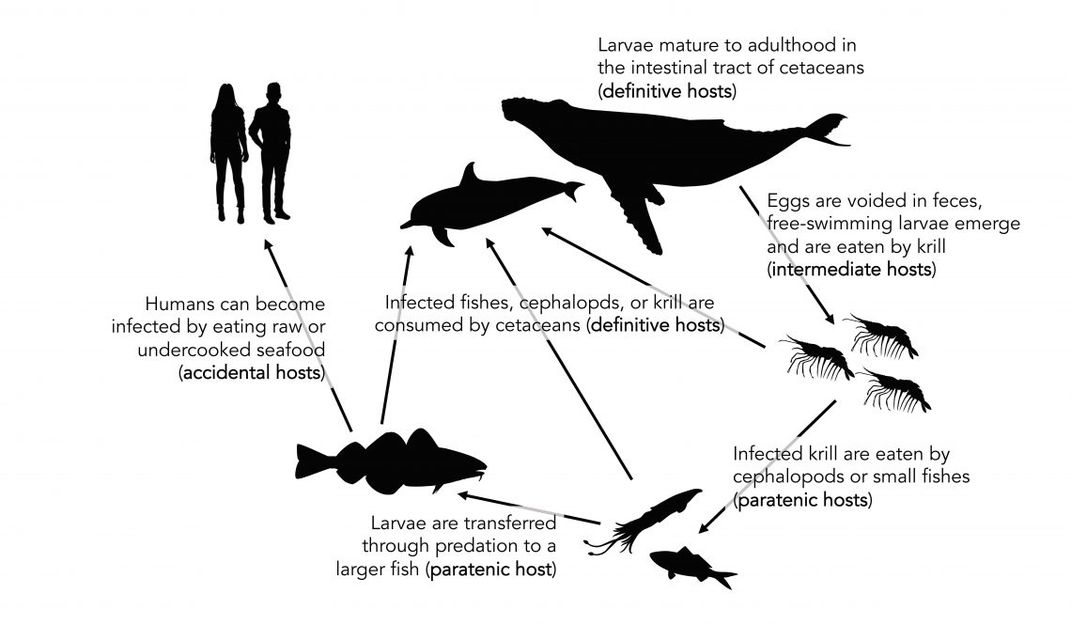

For parasitic worms of the genus Anisakis, life typically goes like this: after floating through the ocean in an egg, they hatch as wriggling larvae with a peculiar desire—to be eaten. Small crustaceans like krill gobble up the larvae, and those infested krill are then eaten by squid or small fish, which are devoured by bigger fish until they finally earn their nickname, whale worms, and end up in the bellies of whales or dolphins where they complete their life cycle by laying eggs that are subsequently ejected in the hosts’ feces.

But sometimes, those big fish full of the worms—like salmon or herring—get intercepted by fishers and end up in markets. Although fish suppliers and sushi chefs diligently remove parasite-infected fish from their wares, occasionally one of those little buggers may wind up in your sushi roll.

Now, new research finds the global population of those parasitic worms, commonly found in sushi and other kinds of uncooked fish, has exploded in recent decades. The worms are 283-times more common than they were roughly 40 years ago, according to a new paper published in Global Change Biology.

For humans, accidentally eating the worms, which are about the size of a nickel, can lead to vomiting and diarrhea. The first documented case of the resulting illness occurred in the Netherlands in 1960 after the unlucky patient had consumed some lightly salted herring. Fortunately, the worms can’t survive in the human digestive tract for long and typically die after a few days. But in fish, squid and marine mammals the parasites can thrive and reproduce.

“When they enter the intestine of a human, it’s a great disappointment to the worm. They’re not going to be able to complete their life cycle there,” Chelsea Wood, a parasite ecologist at the University of Washington, tells Donna Lu of New Scientist.

Freezing or cooking fish kills the parasite, making raw fish the primary risk for most people. But even the risk to frequent sushi consumers is relatively low; the worms are visible to the naked eye so they’re usually picked out by skilled sushi chefs and fish suppliers. However, it’s possible that Anisakis’ growing numbers will cause problems for some marine life, Amber Dance reports in Science News.

Thousands of scientific studies about this parasitic worm have been published over the years, but each captured just a sliver of the species’ overall abundance and geographic range. The new study rolls all this prior research together to provide a global analysis of the worms’ population spanning 1978 to 2015.

The analysis, which included more than 55,000 specimens from 215 fish species, revealed that in 1978, the global average was one worm per 100 fish. By 2015, the average jumped to more than one wriggling parasite per individual fish. The researchers observed the same increase across the board—regardless of location, species or techniques scientists used to find and count the worms.

Anisakis’ prolific rise might not be a huge problem for human health, but it could spell trouble for their marine hosts. In Atlantic salmon, infection can lead to red vent syndrome, which causes the opening of the fish’s reproductive and digestive tract to swell and bleed. Anisakis worms are commonly found in whale necropsies but it’s less clear what harm they may cause the giant marine mammals in life, Wood tells Science News. Inside the marine mammals, the worms do lay eggs, but they typically get pooped out and the parasites’ life cycle begins anew.

Because the worm’s reproductive cycle goes up and down the food chain, Wood says an abundance of the parasites could signal healthy ecosystems. Whale populations, for example, are finally coming back after being decimated by the whaling industry. Because whales are the worms’ preferred hosts, it may be that their increasing numbers are simply a function of healthier global whale populations, says Wood. But other potential explanations abound, such as the potential role of climate change, which could be speeding up the Anisakis life cycle by warming the oceans.

According to Science News, the researchers are now looking into what impacts the increase in the worms’ abundance may be having on vulnerable whale populations, such as the imperiled killer whales of the Pacific Northwest, and probing further back in time to understand whether ocean health or human-caused damage is driving the worm bonanza. And, in case you were wondering, Wood still eats sushi.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)