Peer Into the Past With Photorealistic Portraits of Roman Emperors

Artist Daniel Voshart used machine learning and editing software to create likenesses of 54 ancient leaders

:focal(380x384:381x385)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/83/2e83e5e0-4f81-4b53-bd0a-8113691e759a/composite.jpg)

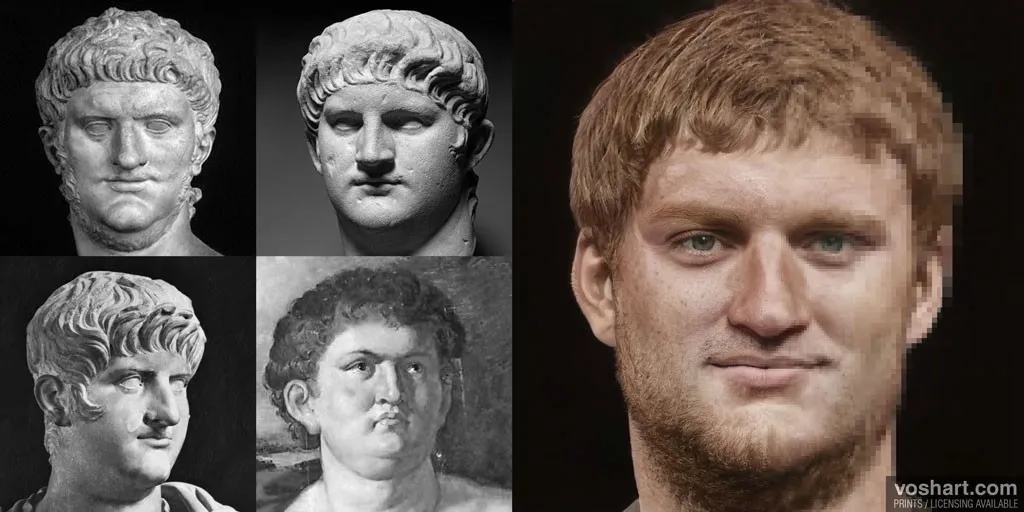

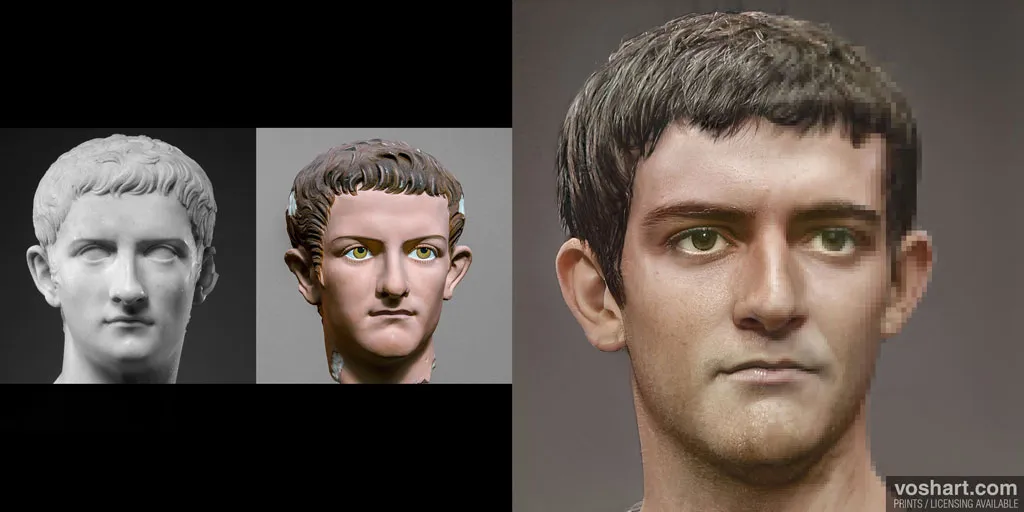

Caligula, the Roman emperor best known for his profligacy, sadism, rumored incestuous relationships and unhealthy obsession with a horse, wasn’t exactly handsome. Contemporary accounts are filled with descriptions of the infamous ruler’s misshapen head, ill-proportioned body, enormous feet and thinning hair. Fully aware of his “naturally frightful and hideous” countenance, according to historian H.V. Canter, Caligula—whose favorite phrase was reportedly “Remember that I have the right to do anything to anybody”—often accentuated his off-putting visage by making faces “intended to inspire horror and fright.”

Millennia after the emperor’s assassination in 41 A.D., two-dimensional depictions and colorless marble busts offer some sense of his appearance. But a new portrait by Toronto-based designer Daniel Voshart takes the experience of staring into Caligula’s eyes to the next level, bringing his piercing gaze to life through a combination of machine learning and photo editing.

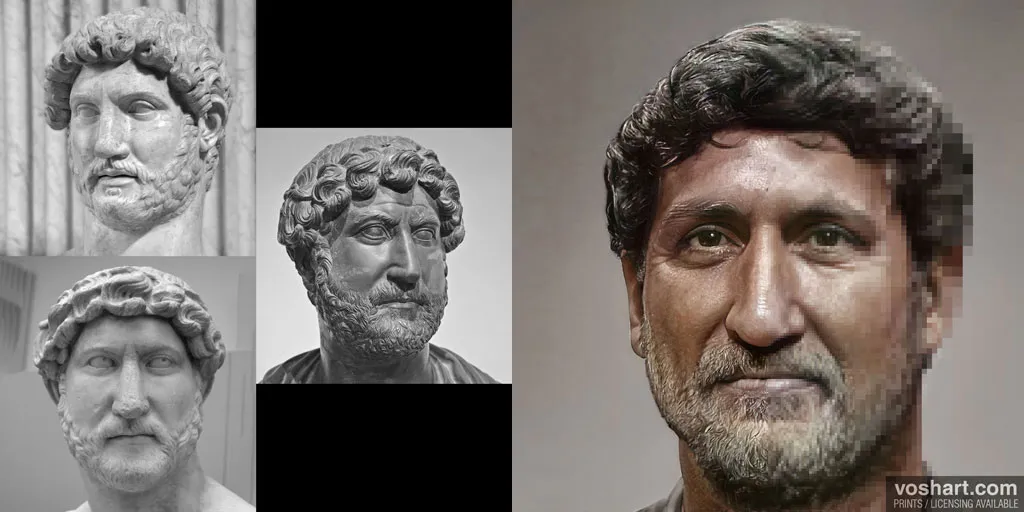

As Voshart explains in a Medium blog post, he drew on 800 images of classical busts, as well as historical texts and coinage, to create photorealistic portraits of the 54 emperors who ruled Rome between 27 B.C. and 285 A.D. Among the men included are Caligula’s nephew Nero, Augustus, Hadrian, Tacitus and Marcus Aurelius. (A poster version of the project is available for purchase on Etsy.)

Per artnet News’ Tanner West, Voshart uploaded his snapshots of stone sculptures to Artbreeder, a generative adversarial network (GAN) that blends images to produce composite creations—in other words, “[T]he tool will combine them together in a sophisticated way to create something that looks … like the two images had a baby.” After several rounds of refining, the artist fine-tuned the likenesses in Photoshop, adding color, texture and other details designed to make the portraits as lifelike as possible.

Crucially, Voshart tells Smithsonian, the project doesn’t claim to offer definitive portrayals of what the emperors actually looked like.

“These are all, in the end, … my artistic interpretation where I am forced to make decisions about skin tone where none [are] available,” he says.

Writing on Twitter, the designer adds, “[E]ach step towards realism is likely a step away from ground-truth.”

To determine the Roman rulers’ likely skin tone and hair color, Voshart studied historical records and looked to the men’s birthplaces and lineages, ultimately making an educated guess. But as Italian researcher Davide Cocci pointed out in a Medium blog post last month, one of the sources cited in Voshart’s original list of references was actually a neo-Nazi site that suggested certain emperors had blonde hair and similarly fair features. Though Cocci acknowledged that some emperors may have been blonde, he emphasized the source’s “clearly politically motivated” nature and reliance on earlier propaganda accounts.

In response to Cocci’s findings, Voshart removed all mentions of the site and revised several portraits to better reflect their subjects’ probable complexions, reports Riccardo Luna for Italian newspaper la Repubblica.

“It is now clear to me [the sources] have distorted primary and secondary sources to push a pernicious white supremacist agenda,” Voshart writes on Medium.

Jane Fejfer, a classical archaeologist at the University of Copenhagen, identifies another potential obstacle in accurately capturing the emperors’ appearances: As she tells Jeppe Kyhne Knudsen of Danish broadcast station DR, classical sculptures and busts often present idealized depictions of their subjects.

Likenesses of Augustus, for example, tend to show him as a young man despite the fact that he reigned for 41 years, while those of Hadrian—who had a well-known penchant for ancient Greece—cast him in the role of a Greek philosopher, complete with long hair and a beard. Portraiture, notes DR, served as a strategic tool for communicating rulers’ “values, ideology and ideals” across their vast kingdoms.

Voshart’s goal “was not to romanticize emperors or make them seem heroic,” he says on Medium. Instead, “my approach was to favor the bust that was made when the emperor was alive. Otherwise, I favored the bust made with the greatest craftsmanship and where the emperor was stereotypically uglier—my pet theory being that artists were likely trying to flatter their subjects.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/e4/a3e4071a-112b-4659-83a8-77eb2f97794a/1_ikkpayp90mzz7vqwknas7a.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/f6/6bf654fe-8f94-467e-af6c-32f0a9c34ec7/augutus.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/00/be0077bc-9fea-44c2-bb0f-183dda57ef8d/diadumenian-final_v4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)