People Have Been Using Big Data Since the 1600s

A humble hatmaker was among the first to compile data on how Londoners lived—and died

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/e6/c7e6716b-d77c-41a2-aeed-6b91578f9377/wenceslas_hollar_-_plan_of_london_before_the_fire_state_2_variant_1.jpg)

John Graunt may have helped to invent the idea of public health statistics, but by day he made hats.

Graunt, born on this day in 1620, was a London haberdasher who was the first to start putting together the information about how people died in the city to help gain a broader understanding of the causes of death and how people lived. In doing so, he gave people a tool that helped pave the way for all kinds of public health innovations, but he also created a historical document that conveys how authorities saw death and life in 1600s London.

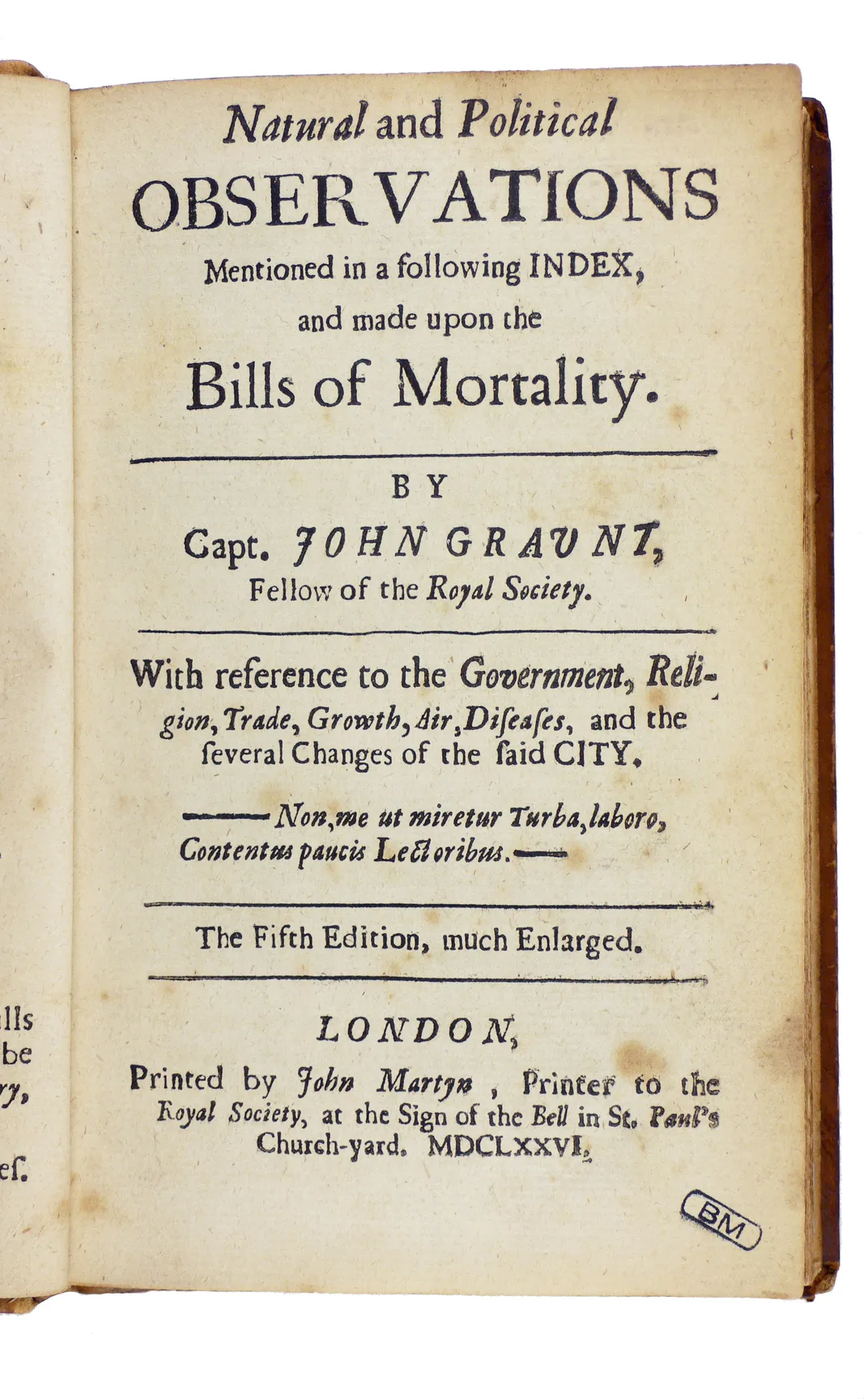

Natural and Political Observations Made Upon Bills of Mortality, first published in 1662 and then revised several times with new information, represented a new way of understanding life and death. “In the landmark report, Graunt calculated death rates, identified variations by subset and pioneered the use of life tables, which show predicted mortality for each age group,” writes Jennie Cohen for History.com.

The city of London issued a weekly report called the “bills of mortality” that specified how many people had died in the preceding week, who they were and how they had died, as well as how many people had been born and christened. This practice had started in the 1500s as the city was wrestling with recurring epidemics of bubonic plague, according to The Royal Society of Medicine.

Overworked clerks who lacked medical training recorded some truly amazing causes of death, including Horsehoehead, Eaten by Lice and Rising of the Lights. “Other more tersely described causes include Overjoy, Purples and Teeth,” writes the society.

Although a number of not-very-descriptive causes of death were recorded—the aforementioned "purples," for example—the bills did help warn people about plague outbreaks, writes Rebecca Onion for Slate. Costing a penny each, they were widely printed and distributed, and contained information about deaths broken down by parish. Readers could see if plague outbreaks were occurring close to their homes or places of employ and be better prepared. Plague awareness became especially important shortly after Graunt's book was published, when the 1665 Great Plague of London struck.

Graunt collected all this information into a number of tables, including one that showed the causes of death for Londoners over the years. He ultimately published a book that collected his research as well as commentary on what the data showed.

“The book came about because Graunt realized that the data being collected in parishes in and around London was open to analysis and interpretation by the new class of ‘natural philosophers,’ or scientists, who, amongst other things, had founded the Royal Society in 1660,” Keith Moore, head of library and archives at the Royal Society, told Cohen.

“Graunt also included commentary on daily life in a teeming urban center that was quickly outgrowing its medieval infrastructure, noting, ‘The old Streets are unfit for the present frequency of Coaches,’” Cohen writes. “He speculated that overpopulation and squalid conditions accounted for Londoners’ mediocre health and frequent bouts with plague, foreshadowing the work of early epidemiologists.”

His work was groundbreaking, but the Londoner wasn’t the first to use life tables: that was the Romans. He was the first to create and widely distribute a life table for a recognizably modern city—and his book went beyond life tables. It “is occasionally curious but most often impressive, even from a perspective of three hundred years,” write demographers Kenneth Wachter and Hervé Le Bras: “Graunt culled a remarkable amount of information from the christening and death lists begun in the later plague period and usually understood its implications.”