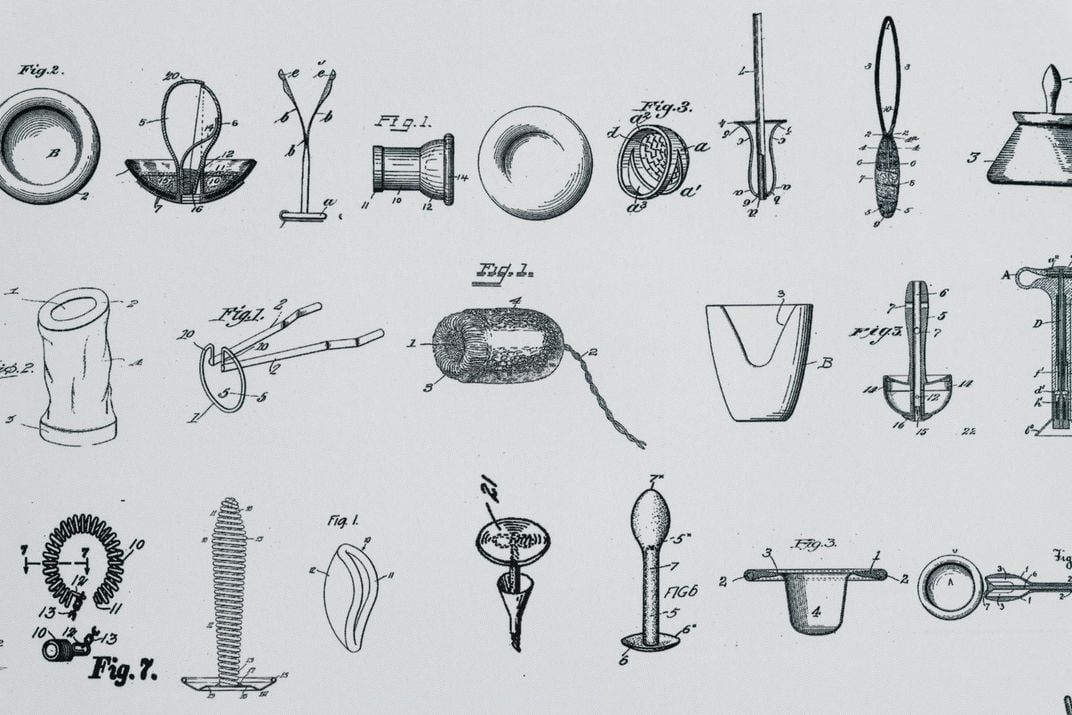

First developed in the mid-19th century, early breast pumps were “essentially glorified milkers,” replicating designs used on cattle with few adjustments, as Megan Garber wrote for the Atlantic in 2013. Over time, Garber added, “male inventors, kindly recognizing that human women are not cows, kept improving on the machines to make them (slightly) more user-friendly.”

Among these upgraded designs was the Egnell SMB Breast Pump. Created by Swedish engineer Einar Egnell in 1956, the glass-and-metal contraption was quieter, less painful and more effective for nursing mothers.

In 2015, almost 60 years after the device’s invention, Michelle Millar Fisher, then a curatorial assistant at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), suggested acquiring it for the collections.

“Why couldn’t it be there, alongside the KitchenAid and Hoover and other things dreamed up in the mid-20th century that are now enshrined in design collections?” she asks the Guardian’s Lisa Wong Macabasco.

Though Millar Fisher’s colleagues rejected the idea, the experience led her and historian Amber Winick to embark on a broader project exploring the connection between reproduction and design. The first stage of the book and exhibition series—titled “Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births”—debuted at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia in May.

As Melena Ryzik reports for the New York Times, curators plan to unveil a larger version of the exhibition at the Center for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia this fall. To accompany these presentations, Winick and Millar Fisher penned a book featuring more than 80 “iconic, profound, archaic, titillating, emotionally charged, or just plain odd” designs that speak to reproductive experiences over the past century, per the Guardian.

“These designs often live in very embedded ways in our memories and our bodies,” the book states, as quoted by Vogue’s Dharushana Muthulingam. “We don’t just remember our first period, but also the technologies that first collected that blood. We don’t just remember the way babies arrive, but also what they were wrapped in when they finally reached our arms.”

Objects highlighted in the Mütter iteration of the exhibition include menstrual cups, speculums and Intrauterine Devices (IUDs). Several breast pumps, such as a 19th-century glass specimen and the streamlined, cordless Willow, are also on display.

The companion book, meanwhile, includes descriptions of pregnancy pillows, C-section curtains, Finnish baby boxes, a 1982 Planned Parenthood booklet, gender-reveal cakes and Mamava lactation pods.

“People’s reactions [to the project] ranged from, like, ‘ick’ and ‘ew’ to ‘women’s issue,’ but the overarching misconception is that it just doesn’t matter,” Millar Fisher tells the Guardian. “It begs the question, who decides what matters? I have yet to meet a museum director who has ever used a menstrual cup or tampon or breast pump. Those are not the experiences of most people who are in positions of power.”

“Designing Motherhood” strives to challenge the stigma surrounding objects associated with pregnancy and reproductive health.

One such artifact is the Dalkon Shield, an IUD available in the early 1970s and ’80s. Thousands of users experienced infections, infertility, unintended pregnancies and even death; victims mounted a multibillion-dollar class-action suit against the product’s developers.

Another long-overlooked artifact featured in the project is the Predictor Home Pregnancy Test Kit, which was created by graphic designer Margaret Crane in 1967. According to the Times, Crane developed the device—the first at-home pregnancy test—after seeing rows of test tubes awaiting analysis in the offices of her employer, a New Jersey pharmaceutical company. Determined to give women the ability to test themselves at home, she pitched the idea but was quickly shot down. Then, Crane’s bosses decided to move forward with the concept—without letting her know.

Crane didn’t go down without a fight: She crashed a corporate meeting and convinced the company to move forward with her prototype, a sleek, straightforward design lacking the “flowers and frills” that male designers had put on their proposed models, according to Pagan Kennedy of the New York Times. Though she was listed as the inventor on a 1969 patent, she was pressured into signing away her rights for just $1—a sum the company never actually paid out.

In 2015, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History acquired one of Crane’s prototypes, bringing renewed attention to her pioneering invention.

“A woman should not have to wait weeks for an answer,” Crane told a curator at Bonhams, where the prototype went up for sale, per Smithsonian magazine’s Roger Catlin.

Though reproduction affects all people’s lives at one point or another, the subject is seldom discussed publicly: As Vogue points out, the Affordable Care Act requires employers of a certain size to provide lactation spaces, but less than half of mothers actually have access to one. The United States lacks federally mandated paid maternity leave, and many women of color have even less access to paid leave than their white counterparts. The Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these inequalities.

“Designing Motherhood” may not be able to change policies regarding reproductive health, but the project does amplify conversations surrounding these issues.

“[M]useums neglecting designed objects that address the needs of women's bodies is not an accident,” Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, a curator of contemporary design at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, tells the Times. “Rather, it’s symptomatic of an historically male dominated curatorial and industrial design field; of a culture that prioritizes fantasy over biology; that privatizes birth; that commodifies women's bodies. Design museums are in a unique position to illuminate social and historical inequities and advancements through product innovation, but still hesitate.”

“Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births” is on view at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia through May 2022. A larger version of the exhibition will debut at the Center for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia in September.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/aa/feaadd59-8929-43fc-baf7-c21a5d8eab1f/obile_crown.jpg)

:focal(617x291:618x292)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/ab/92aba4f1-5f9e-49a0-a8bb-7f0d7e1bb08e/crown_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)