Did This Couple Steal a $160 Million de Kooning?

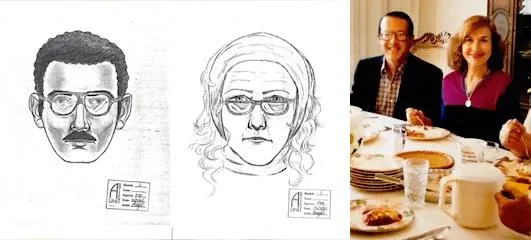

The Thanksgiving snapshot places Jerry and Rita Alter in Tucson, Arizona, just a day before the 1985 heist

:focal(512x273:513x274)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/0e/ee0eab5a-3a91-4021-9b0c-84f497d107e7/jerry_rita_alter-youtubewfaa-1-1024x544.jpg)

It was the day after Thanksgiving 1985 when the couple arrived at the University of Arizona Museum of Art. Both were wrapped in thick winter coats—hers red, his blue. It was just after opening, and as the woman began chatting with a security guard, the man slipped away to the second floor. Less than 10 minutes passed before the couple hastily departed in a rust-colored car. With them went the museum’s prized painting—Willem de Kooning’s 1955 “Woman-Ochre,” then valued at $400,000 and now worth an estimated $160 million.

Thirty-two years later, “Woman-Ochre” resurfaced in a surprising locale: behind the door of a recently deceased couple’s New Mexico bedroom. No one knew how the painting had ended up in the hands of Jerry and Rita Alter—a retired professional musician-turned-band teacher and speech pathologist, respectively—and the couple was no longer around to provide an explanation. But, Anne Ryman reports for the Arizona Republic, a newly discovered photograph from that Thanksgiving of 1985 may be the key to solving the three-decade mystery.

According to Ryman, Rita’s nephew Ron Roseman, executor of the pair’s estate, chanced upon the snapshot while sorting through family photo albums. The picture finds Jerry and Rita sitting side-by-side, enjoying dessert at a relative’s Tucson, Arizona, home alongside their adult son and an array of other family members.

Juxtaposed with the composite sketch released by law enforcement following the theft, the couple’s resemblance to the culprits is striking. Jerry’s glasses mirror those of the male suspect, and his dark hair, albeit straight rather than curled, is cut in the same shape. Rita’s hair, too, matches that of the female suspect, whose reddish-blonde hair reached just past her shoulders. Perhaps most importantly, the photo places the Alters in Tucson, home of the University of Arizona museum, one day before the heist.

NPR’s Vanessa Barchfield writes that just after the thieves departed the museum, the security guard who had spoken with the woman headed to the second floor. There, he found an empty frame, brutally slashed to remove the de Kooning once held within.

Police had little to go on: The museum had no surveillance cameras installed, and there were no fingerprints left at the scene. The frame remained untouched for years, waiting for the return of its prized canvas.

Jerry Alter died in 2012, and Rita in 2017. According to the New York Times’ William K. Rashbaum, Roseman, executor of the estate, commissioned antiques dealer David Van Auker to appraise the contents of the Alters’ three-bedroom, 20-acre home. He found “Woman-Ochre” hidden between a corner of the master bedroom and the door, placed in a way that it remained obscured from visitors. Unaware of the painting’s provenance but intrigued by its bold brushstrokes, Van Auker purchased the work and exhibited it in his store.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/ac/fdacac2d-94d0-4720-9d7d-a9f1bd941ef6/bob_demers_uanews.jpg)

The first customer to see “Woman-Ochre” commented, "I think that's a real de Kooning," according to a University of Arizona press release. Unconvinced, Van Auker demurred, but after several additional customers voiced similar opinions, he turned to Google and realized he was in possession of a stolen masterpiece. Following extensive back-and-forth with museum officials, the painting was authenticated and, after a 32-year absence, returned to its rightful home.

The Washington Post’s Antonia Farzan reports that there is a significant amount of circumstantial evidence tying the Alters to the heist. The couple owned a red sports car similar to the one used by the thieves, and photographs show Rita donning a red coat matching that of the female thief. Analysis of the retrieved work shows it was only reframed once in the aftermath of the theft, suggesting it stayed with one owner during the entire period.

Another piece of the puzzle is the couple’s income. Despite working in public schools for most of their careers, the Alters were financially stable enough to visit 140 countries across all seven continents. At the time of their deaths, the couple had more than a million dollars in their bank account, Danny Udero writes for the local Silver City Sun-News.

Perhaps most telling, according to Farzan, is “The Eye of the Jaguar,” a short story published by Jerry the year before his death. The tale revolves around a security guard responsible for watching over a famed emerald. One day, an older woman and her granddaughter visit the museum, leaving quickly enough to arouse the guard’s suspicions. He attempts to confront the pair as they drive away, but the woman runs him down, leaving no clues in her wake. By the end of the story, the emerald is safely stashed away, visible only to the woman and her granddaughter, who triumphantly conclude, “And two pairs of eyes, exclusively, are there to see!”

There are clear parallels between the story and the couple's hidden masterpiece—it's easy to suspect Jerry wrote the piece to pay covert tribute to a successful heist, but there's no way of knowing for certain.

Roseman is understandably reluctant to view his aunt and uncle as criminals. He suggests the pair might have purchased the painting from the real culprits, unaware of its shadowy provenance.

Still, he admits to Ryman that in the face of mounting evidence, “I can see that it's possible.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)