The Poignant Wartime Diary of a Jewish Teenager Living in Poland Has Been Published in English

Renia Spiegel was killed by the Nazis when she was 18 years old

:focal(487x171:488x172)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/cd/3ecd1ea3-f4f6-4d2e-b551-36224b2d2067/renia.jpg)

Over the course of three years and 700 diary pages, a Jewish teenager named Renia Spiegel chronicled the unraveling of her life after her native Poland was invaded by the Soviets, then the Nazis. She was shot dead in the summer of 1942, when she was just 18 years old. But as Robin Shulman reported for the November 2018 issue of Smithsonian magazine, her diary survived the war, locked away in a safe deposit box for decades. Now, this precious, poignant historic document has been published in English in full for the first time.

The diary has drawn inevitable comparisons to Anne Frank, the Dutch-Jewish teenager who famously diarized her own wartime experiences. Both were lucid writers, articulate and insightful in spite of their young age. Both wrote about love and coming of age even as they grappled with the horrors around them. Both of their lives were cut tragically short. At the same time, clear differences emerge. "Renia was a little older and more sophisticated, writing frequently in poetry as well as in prose," Shulman writes. "She was also living out in the world instead of in seclusion."

While Spiegel's diary has been in her family's possession for years, it was only published in Polish in 2016. Smithsonian published the first English-translated excerpts of the diary last year. "Reading such different firsthand accounts," Shulman adds, "reminds us that each of the Holocaust’s millions of victims had a unique and dramatic experience." For instance, as Alexandra Garbarini, a professor and historian at Williams College in Massachusetts, points out in a recent interview with Joanna Berendt of the New York Times, Spiegel’s diary covers not only the Nazi occupation, but also Stalin’s totalitarian regime.

“This is such a complete text,” Garbarini says. “It shows the life of a teenager before the war, after the war breaks, until she has to move to the ghetto and is executed. It’s absolutely remarkable.”

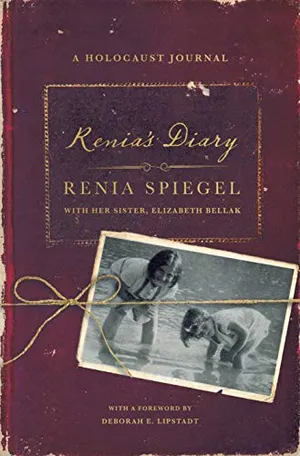

Renia's Diary: A Holocaust Journal

The long-hidden diary of a young Polish woman's life during the Holocaust, translated for the first time into English

Spiegel lived in the city of Przemyśl and was 15 years old in 1939 when the war broke out. At the time, Spiegel and her younger sister, Ariana, were staying with their grandparents. Her mother, according to Shulman, had been spending long stretches of time in Warsaw promoting Ariana’s career; Spiegel’s sister was a child star who appeared on stage and screen.

“[T]he truth is, I have no real home,” Spiegel wrote in her first diary entry—January 31, 1939. “That’s why sometimes I get so sad that I have to cry. I miss my mamma and her warm heart. I miss the house where we all lived together.” And, as she was want to do when her emotions reached a crescendo, Spiegel expressed herself in a poem:

Again the need to cry takes over me

When I recall the days that used to be

Far... somewhere...too far for my eyes

I see and hear what I miss

The wind that used to lull old trees

And nobody tells me anymore

About the fog, about the silence

The distance and darkness outside the door

I will always hear this lullaby

See our house and pond laid by

And linden trees against the sky…

Her troubles compounded as the circumstances became increasingly dire for Jewish people under the Nazi regime. “We wear the armbands, listen to terrifying and consoling news and worry about being sealed off in a ghetto,” Spiegel wrote in 1941. But against this dark backdrop, romance blossomed between Spiegel and a young man named Zygmunt Schwarzer. The two shared their first kiss just days before the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union.

Amid the looming threat of deportation to concentration camps, Schwarzer arranged for Spiegel and his parents to go into hiding in the attic of a Przemyśl home. Spiegel left her diary with her boyfriend for safekeeping. The hiding place was, however, discovered by the Nazis and all three of its occupants were summarily executed. It is Schwarzer who penned the last words in Spiegel’s diary:

“Three shots! Three lives lost! Fate decided to take my dearest ones away from me. My life is over. All I can hear are shots, shots … shots.”

Schwarzer was ultimately sent to Auschwitz, and he survived. It is not clear what he did with the diary before his deportation, or how he retrieved it. But in the early 1950s, he presented it to Spiegel’s mother and sister, who had managed to escape to Austria, and then to New York.

“It was Renia’s diary, all seven hundred pages of it,” Spiegel’s sister, who now goes by Elizabeth Bellak, tells Rick Noack of the Washington Post. “My mom and I broke down in tears.”

Bellack couldn’t bring herself to read the diary—“It was too emotional,” she says in an interview with Berendt—so she locked it away in a bank vault. But her daughter, Alexandra Bellack, recognized the significance of the diary and worked to have it published.

Alexandra tells CNN’s Gianluca Mezzofiore that the diary, though written nearly 80 years ago, seems acutely relevant today “with the rise of all the ‘isms’—anti-Semitism, populism and nationalism.”

“[B]oth me and my mom,” she adds, “saw the necessity in bringing this to life."

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.