Powerful Computers Are Piecing Together 1,000 Years of Jewish Chronicles

Hundreds of thousands of text fragments chronicle everything from marriage dowries to shopping lists to ancient religious texts

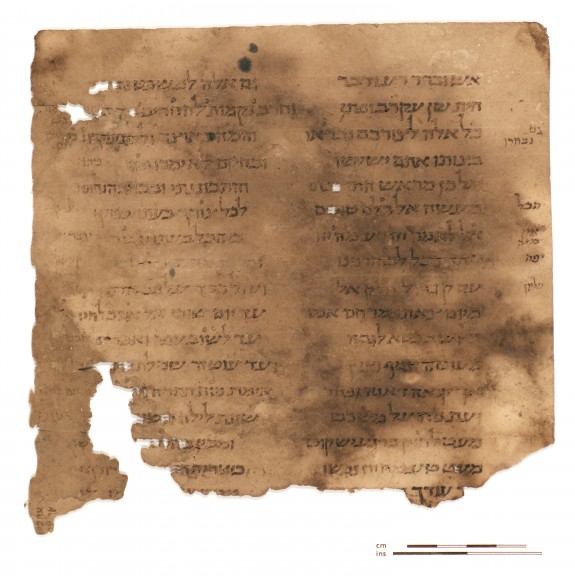

The Hebrew text of the book of Ben Sira, purchased by Gibson and Lewis. Photo: University of Cambridge

One hundred and seventeen years ago, twin sisters Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson, both highly accomplished academics, were traveling through Cairo. From a bookseller in town, says the New Yorker, the pair purchased a small set of ancient Hebrew texts. One of the writings turned out to be an original copy of the proverbs of Ben Sira.

But that find was just a clue to the trove of Hebrew documents that Cairo was keeping. Seeing the documents upon Lewis and Gibson’s return to England, Solomon Schechter, another scholar at Cambridge, traveled to Cairo. Schechter, says the New Yorker,

ventually ma his way to the Ben Ezra synagogue—the site, according to legend, where baby Moses had been found in the reeds. Deep within the building, in a hidden repository called a genizah (from the Hebrew word ganaz, meaning to hide or set aside), Schechter uncovered more than seventeen hundred Hebrew and Arabic manuscripts and ephemera.

According to Jewish traditions, any writings that bear a reference to God must be buried. Often, a pile of works is collected and then buried together. That was the intention for the writings found near Cairo, but for some reason the documents were just never interred.

The Jews of Fostat, though, preserved not only sacred texts but just about everything they ever wrote down. It’s not precisely clear why, but Outhwaite told me that medieval Jews hardly wrote anything at all—whether personal letters or shopping lists—without referring to God. (Addressing a man might involve blessing him with one of God’s names; an enemy might be cursed with an invocation of God’s malice.)

Because of this, the collection of documents discovered in the Cairo genizah was a glimpse into Jewish life from the ninth to 19th centuries.

We see what people bought and ordered, and what got lost in shipments between Alexandria and the Italian ports. We learn what clothes they wore: silks and textiles for the middle classes, from all over the known world. The Genizah includes prenuptial agreements and marriage deeds from the eleventh century listing the full inventory of a woman’s trousseau. It also contains the oldest-known Jewish engagement deed, from 1119, which was invented to grant a woman (and her dowry) legal protection as the time period between betrothal and marriage changed in medieval Egypt.

“In some ways,” says the Jewish Daily Forward, “the contents of the Cairo Genizah are more important than the Dead Sea Scrolls, several scholars believe. While the Dead Sea scrolls were the religious literature of a small sect that lived in the desert for a few years, the Cairo Genizah told the story of the day-to-day details of a millennium of Jewish life, from the mundane to the magnificent.”

But many of the hundreds of thousands of texts that make up to collection are just fragments, worn and weathered with time. “ecause a genizah is essentially a garbage can,” says the New York Times, “most of the manuscripts were tattered and torn; Solomon Schechter, one of the earliest to study the collection, called it “a battlefield of books.”

Efforts have been made to piece the fragments back together, but it is a slow, painstaking affair. More than a decade of work has already gone in to digitizing the fragments, and now a massive computing project is giving the reconstruction efforts a boost. In Tel Aviv University, says the Times, “more than 100 linked computers… are analyzing 500 visual cues for each of 157,514 fragments, to check a total of 12,405,251,341 possible pairings.”

Work so far using the computers, says the Jewish Daily Forward, has been able to do “more in a few months than in 110 years of conventional scholarship.” According to the Times, the computerized reconstruction effort should be done within a month. More than just offering a view into Jewish history, the fully reconstructed genizah would tell a new side of the tale of the Middle East, one captured by ordinary people living in a multicultural community in the mouth of the Nile.

More from Smithsonian.com:

The Dead Sea Scrolls Just Went Digital

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)