Prehistoric Great White Shark Nursery Discovered in Chile

Young sharks grew up here millions of years ago, scientists say

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/27/2f27a1b3-ffac-46a3-ac4c-ed1463fe9864/great_white_shark.jpg)

Great white sharks have earned fame and captured the popular imagination with their impressive size, hunting savvy and fearsome serrated teeth. However, human pollution, poaching and fishing, combined with the sharks’ naturally low birth rates and long lifespans have made the fish vulnerable to extinction—and difficult for scientists to study.

One new discovery sheds light on the history of this elusive fish. A team of scientists recently found evidence of a prehistoric great white shark nursery in the Coquimbo region of northern Chile, according to a paper published this month in Scientific Reports. These sharks likely lived between 2.5 to 5 million years ago, during the Pliocene Epoch, according to a statement.

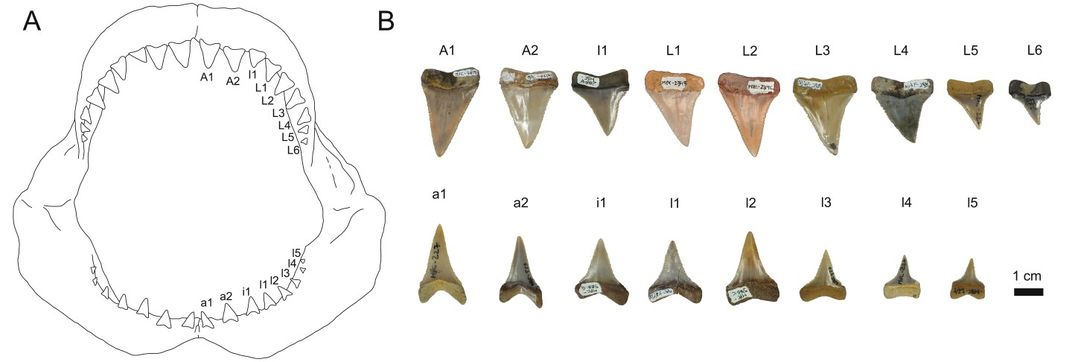

Led by Jaime A. Villafaña at the University of Vienna, the team was studying great white shark teeth from three locations in South America when they realized that most of the teeth from the Coquimbo site were from juveniles, Hannah Osbourne reports for Newsweek. “We were quite surprised to find such high numbers of juvenile white shark teeth in the area,” Jürgen Kriwet, study co-author, told Newsweek in an email.

As Jake Rossen reports for Mental Floss, great whites protect their young, known as pups, in nurseries, usually in shallow seas or protected bays. Adult sharks guard their young from predators in these designated places until the pups can survive on their own. Great whites, or Carcharodon carcharias, reach sexual maturity in their twenties or thirties and can grow to be more than 60 years old.

Researchers were able to estimate the body sizes and ages of these prehistoric sharks based on the size of their teeth, Ben Coxworth reports for New Atlas. The high concentration of juvenile shark teeth discovered in one area suggests that great white sharks have used nurseries to raise their young for millions of years, according to the study.

As Douglas McCauley, an ecologist at the University of California Santa Barbara who was not involved in the study, tells Newsweek, the discovery of an ancient nursery isn’t the researchers’ only exciting find. “One thing that is interesting is that this study suggests white sharks may have been a lot more common in the past off the Pacific coast of South America than they are today,” he says. “The fossil record sheds they report on appear to paint a picture of Peru and Chile a million years ago that hosted thriving nurseries full of baby white sharks and buffet zones teeming with adults. But today white sharks are fairly rare in that region.”

Scientists today know of only a few active great white shark nurseries. The research group Ocearch discovered one nursery off the coast of New York in 2016—the first of its kind found in the North Atlantic, as Jason Daley reported for Smithsonian magazine at the time.

Researchers say that further study of this prehistoric nursery could aid current conservation efforts by helping scientists understand how nurseries aid great white shark survival. “If we understand the past, it will enable us to take appropriate protective measures today to ensure the survival of this top predator, which is of utmost importance for ecosystems,” Kriwet says in the statement.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)