This Prehistoric Sea Creature Had Fanged, Killer Babies

The discovery of a juvenile Lyrarapax unguispinus fossil reveals that even the tiny terrors had a developed claw-like appendage and sharp teeth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/08/9f08a35b-8783-4e82-830a-1a4723c4a959/sea_killer.jpg)

Around 500 million years ago, a fearsome arthropod known as Lyrarapax unguispinus glided through Earth’s seas, searching for prey. L. unguispinus, which could grow to more than three feet long, had a claw-like appendage on its head for scooping up tasty critters. It would then devour its prey with the serrated teeth that lined its mouth. And as Brandon Specktor reports for Live Science, the discovery of a juvenile L. unguispinus fossil has revealed that these prehistoric hunters were well-equipped to kill from an early age.

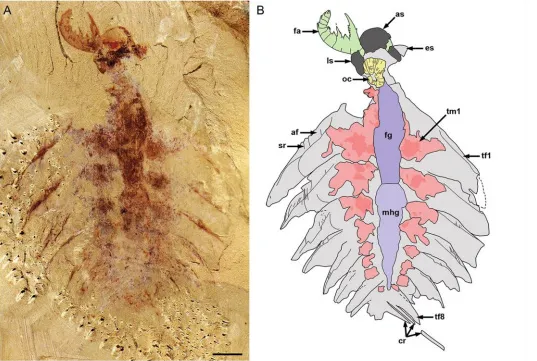

The fossil was found in a piece of 518-million-year-old shale in China’s Yunnan province. Describing their discovery in National Science Review, an international team of paleontologists note that the fossil, which is nearly complete, measures just three quarters of an inch (about 18 millimeters) long. The specimen is thus the smallest-known “radiodontan,” a group of arthropods that had circular mouths lined with teeth. But though it was but tiny, it was fierce: The L. unguispinus baby boasted “adult-like morphology,” including the claw and mouth full of teeth, the study authors write.

Like its adult counterparts, the little arthropod had a spiny raptorial appendage used for grasping prey and the radiodontan’s characteristic circular mouth filled with sharp teeth. This discovery isn’t necessarily surprising; modern arthropods, like mantises and arachnids, are also well-developed predators from an early age, the researchers note. But prior to the discovery of the juvenile L. unguispinus fossil, very little was known about the offspring of this ancient predator.

As Ruth Schuster points out in Haaretz, the fossil discovery also contributes to our understanding of the “Cambrian explosion”—the sudden and rapid proliferation of a wide variety of species starting around 542 million years ago, during the Cambrian period. Prior to this point, Douglas Fox explains in Nature, the Earth’s seas held so little oxygen that only simple animals “whose bodies resembled thin, quilted pillows” could survive. (New research has been challenging this idea of pre-Cambrian life. Fossil footprints discovered just recently that predate the Cambrian imply that legs and feet might have predated the so-called explosion.)

The forces that drove the Cambrian explosion are not entirely clear, but one theory posits that a slight increase in the oceans’ oxygen levels allowed predators to flourish, which in turn caused the soft-bodied creatures of the pre-Cambrian era to evolve defensive features like exoskeletons.

As large apex predators, adult L. unguispinus were likely drivers of what scientists sometimes refer to as the “evolutionary arms race” of the Cambrian explosion. According to the study authors, the discovery of the juvenile fossil suggests that L. unguispinus babies also played a key role in this period of widespread speciation, putting “extra selective pressure” on animals—particularly small ones—to evolve features that would prevent them from becoming the tiny terrors’ lunch.