Is This Landscape a Long-Lost Vincent van Gogh Painting?

A controversial art collector claims that a depiction of wheat fields in Auvers is the work of the famed Impressionist

:focal(373x293:374x294)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/87/b687abf9-0276-48eb-b218-93400802934c/private_colleciton.jpg)

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, art historians cast increasing doubt on the authenticity of artworks attributed to Vincent van Gogh. A 1997 investigation by the Art Newspaper, for instance, suggested that at least 45 van Gogh paintings and drawings housed in leading museums around the world “may well be fakes.” In the words of scholar John Rewald, forgers have likely replicated the Impressionist artist’s work “more frequently than any other modern master.”

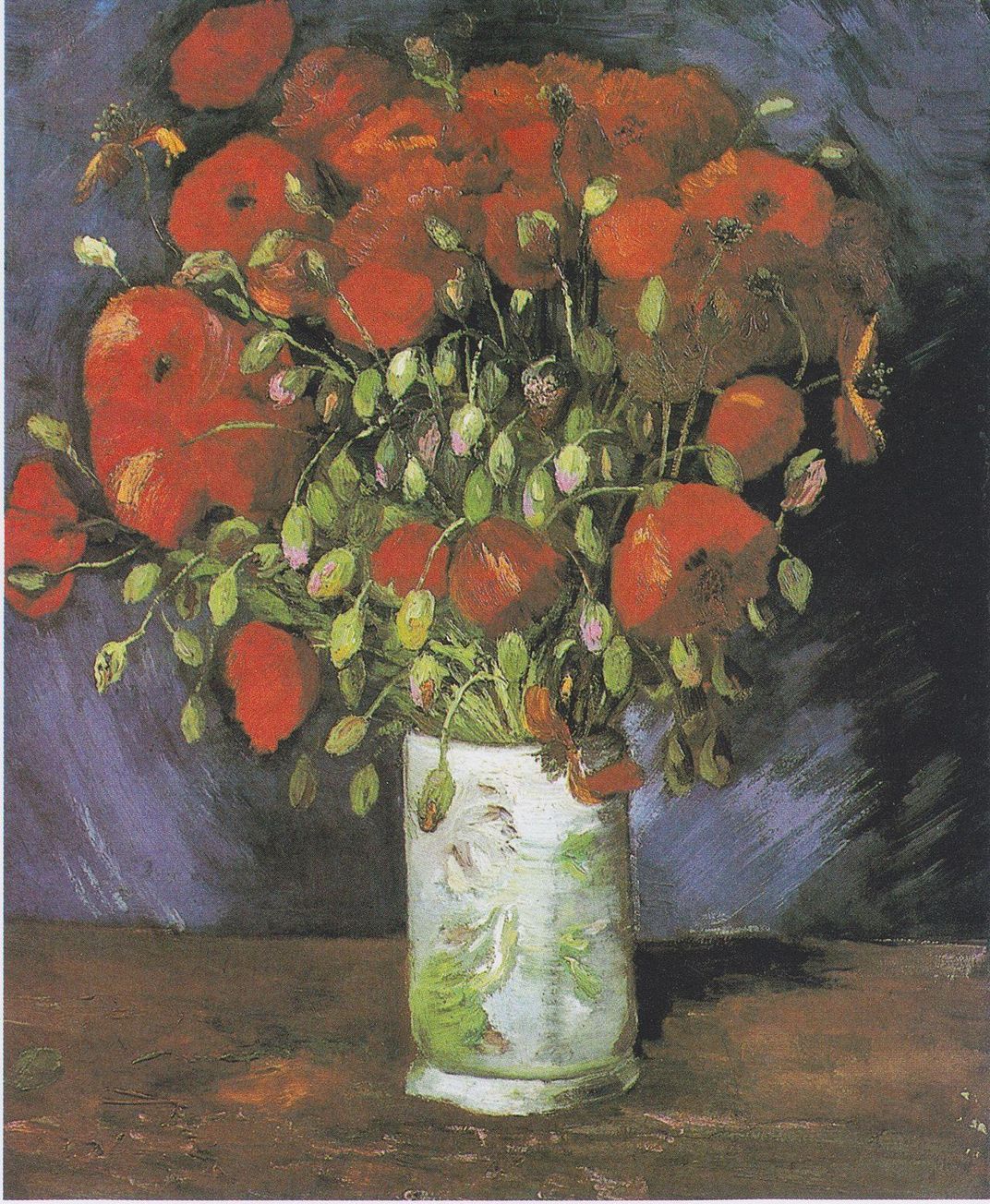

This trend has shifted in recent years, with high-tech authentication tools enabling researchers to deem “questionable works” acceptable again, wrote Martin Bailey for the Art Newspaper in 2020. Among the newly authenticated van Gogh paintings are Sunset at Montmajour, a vibrantly colored landscape that remained hidden in a Norwegian attic for years, and Vase With Poppies, which had confounded scholars for nearly 30 years.

“Until recently, the artist’s oeuvre had been reduced,” noted Bailey, “but now it is being expanded again.”

As Anthony Haden-Guest reports for Whitehot magazine, a newly resurfaced landscape uncovered by a controversial New York art collector may be the next painting to join van Gogh’s catalogue raisonné, or comprehensive list of known works.

Stuart Pivar, who co-founded the New York Academy of Art in 1982 alongside renowned Pop Art icon Andy Warhol, tells Whitehot that he chanced upon the painting at an auction outside of Paris. The work depicts wheat fields in the French city of Auvers, where van Gogh spent the final months of his life.

Pivar has previously made headlines for his litigious nature, including a suit against the academy, and his links to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, whom he described to Mother Jones’ Leland Nally as his “best pal for decades.” The polarizing art world figure added that he had severed ties with Epstein—a “very sick man”—after learning of allegations against the financier.

Per commentary provided by Michael Mezzatesta, director emeritus of the Duke University Museum of Art, and quoted by Whitehot, “The picture is in pristine original condition, painted on a coarse burlap canvas consistent with those used by van Gogh late in his career. … The reverse of the canvas bears the signature ‘Vincent’ in an entirely credible hand and what appears to my eye a date ‘1890’ rendered in the fugitive walnut brown ink typical of many of van Gogh’s drawings.”

In hopes of authenticating his find, Pivar reached out to the Amsterdam-based Van Gogh Museum, which assesses just a few potential paintings each year. Though the museum is currently closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic and unable to accept authentication requests, representatives told Pivar that “[w]e have decided to make an exception for you,” according to an email seen by Page Six’s Emily Smith.

“This is what we are considering to be the greatest art find in 100 years,” Pivar claims to Page Six.

Titled Auvers, 1890, the work shows a fluidly rendered, yellow-and-green landscape dotted with houses and verdant trees. The scene depicts the titular town, where van Gogh lived in the weeks leading up to his death in July 1890. During the last two months of his life, the artist created more than 70 pieces in Auvers, wrote Lyn Garrity for Smithsonian magazine in 2008.

If van Gogh did, in fact, create the 3- by 3-foot work, then it would be the largest in his oeuvre, as well as the only one painted on a square canvas, reports Jenna Romaine for the Hill.

Whitehot notes that a label on the back of the painting lists Jonas Netter, a well-known collector who helped promote Amedeo Modigliani and other artists working in 20th-century Montparnasse—as a previous owner. The number “2726” is written in chalk on the back of the canvas, and a still-to-be identified wax seal is visible on its wooden frame.

“The origin of this picture is from people who do not want to be identified,” Pivar tells Page Six. “It was [originally] from an obscure auction in North America. The people involved are not art people, and I made promises to them not to reveal who they are. At some point, the history might emerge because of the importance of the picture.”

According to Bailey of the Art Newspaper, the recent uptick in authenticated van Gogh works owes much to the “systematic study of paintings and drawings by specialists at the Van Gogh Museum.” Previously, attributions largely came down to individual scholars’ judgment.

Per the museum’s website, its offices receive around 200 authentication requests annually. The majority are identified as reproductions or works “not related stylistically” to the artist, but an average of 5 out of every 200 merit further study, including technical analysis at the museum.

Whether Auvers, 1890, will be one of these lucky few remains to be seen.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)