Proposed Test Heats Up the Debate on Solar Geoengineering

Harvard scientists are moving ahead with plans to investigate using particles to reflect some of the sun’s radiation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/82/5b8259db-f448-40c0-a91f-47ae52036764/706436main_20121114-304-193blend_m6-orig_full.jpg)

Last week, at the Forum on U.S. Solar Geoengineering Research, Harvard engineer David Keith announced tentative plans to launch his latest solar geoengineering project—the largest test yet for the controversial method of reducing the impacts of climate change. The team plans to spray particulate into the atmosphere, reflecting some of the sun's radiation back into space in hopes of partially offsetting the predicted global warming—similar to how erupting volcanoes spew dust and gasses. But critics worry the plan could do more harm than good.

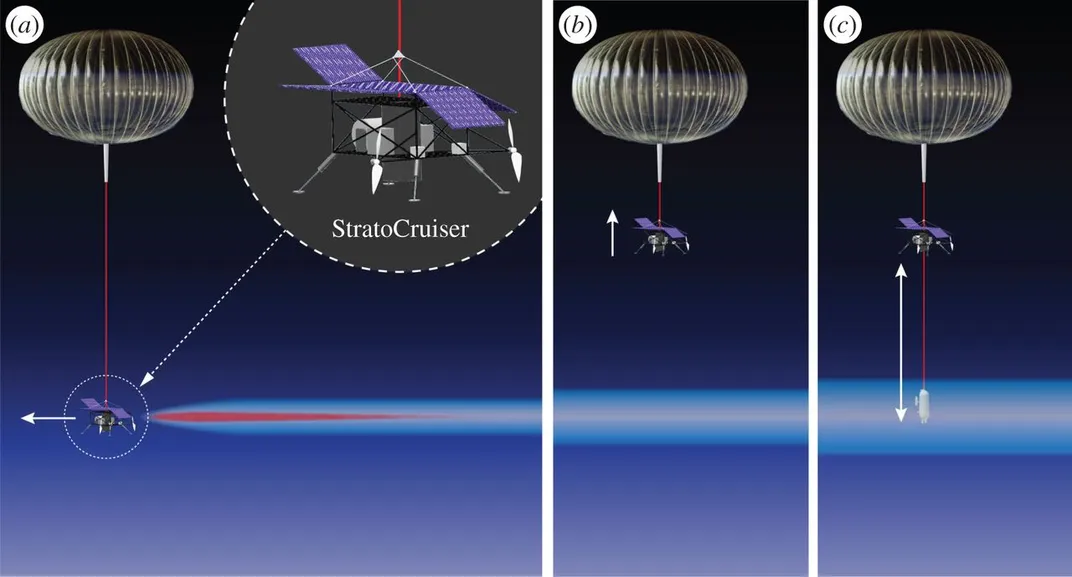

As James Temple writes for MIT Technology Review, Keith and his partner Frank Keutsch developed the "Stratocruiser," which is essentially a gondola decked out with propellers and sensors attached to a high-altitude balloon. The device is bound for the stratosphere, the mid-level of the atmosphere roughly 12 miles above earth, where it will release a spray of sulfur dioxide, alumina or calcium carbonate. They hope to launch the device next year from Tucson, Arizona.

The Stratocruiser will take a slew of measurements, including the particles' reflectivity, duration in the atmosphere, and interactions with other atmospheric elements. If the experiment goes well, it will produce a plume about 300 feet wide and two-thirds of a mile long, Berman reports. In total, the test will release about as much sulfur into the atmosphere as one intercontinental flight. If measurements indicate a drop in ozone, the researchers plan to abort the test.

Keith has used computer modeling to simulate what releasing these materials might do to the atmosphere. But, as he tells Temple, computer models aren’t enough. “You have to go measure things in the real world because nature surprises you,” he says.

Such large-scale environmental alterations are far from new and have long been fodder for science fiction movies and books—just see the movie Snowpiercer, in which engineers cause a global ice age. Apart from cloaking the planet in ice, however, the criticism of the method comes from two main arguments, reports Robby Berman at Bigthink. First, it’s difficult to control and predict the outcome of such large-scale endeavors, Berman writes. Second, relying on and investing in large-scale engineering projects could take the focus away from and downplay the need to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Part of the concern comes from the fact that the technology is "already relatively cheap and available," Tim McDonnell writes for Mother Jones. And there is still little known about the effects of spraying different particulate in the sky. Would it hurt photosynthesizers? Would it cause acid rain? Would we have to continue doing it indefinitely?

But not everyone is staunchly against the idea. A 2015 report from the National Academies of Science suggests that messing with the climate now would be “irrational and irresponsible.” But they also acknowledge that the effects of climate change are starting to bear down, and it would be "prudent" to continue investigation into small-scale experiments like Keith’s.

Politics, however, have further muddied the waters. As Martin Lukacs points out in a recent article in the The Guardian, many people in the fossil fuel industry and climate change critics favor investment in solar geoengineering projects. Silvia Riberio, Latin America director of the ETC Group, which monitors technology, tells Lukacs that a push for solar geoengineering is just a smokescreen that presents a silver bullet for climate change while allowing the continued extraction of fossil fuels and unregulated emissions.

But Keith and collaborator Gernot Wagner disagree. In response, the duo published an article arguing that solar geoengineering is not simply a techno-ruse for the fossil fuel industry. “Fear of solar geoengineering is justified. So is fear of the largely unaccounted-for tail risks of climate change, which make the problem much worse than most realize,” they write. “Ending fossil fuels will not eliminate climate risks, it just stops the increase of atmospheric carbon. That carbon and its climate risk cannot be wished away.”

Keith also argues that the current low cost and availability of carbon capture is a positive, noting that at $10 billion per year, it would be a small investment compared to the damage climate change could cause.

Overall these projects could be positive, but should be approached with a large dose of caution, Jane Long, former associate director at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, warns Temple. These types of experiments need lots of oversight, public input and transparency, she says. But at the same time, such large-scale interventions are becoming increasingly necessary.