The Public Finally Has Access to an Accurate List of Japanese Americans Detained During World War II

Researchers who spent years fixing errors in shoddy government records have partnered with Ancestry to make a wide selection of historical documents related to the period available for free

:focal(1500x1236:1501x1237)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/d2/1fd2de06-545a-4b6c-9b7b-9c1d999abacb/arcadia_california_attendants_register_arrivals_at_santa_anita_assembly_center_and_assign_them_fa____-_nara_-_537045.jpg)

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States’ government incarcerated more than 120,000 Japanese Americans—two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens—over fears they might help imperial Japan during the war. Amid a fresh wave of anti-Japanese sentiment, these Americans were forced to leave behind their homes and belongings, then report to roughly 75 sites around the country. Surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, they were stripped of their identities and remained incarcerated until after the war ended.

Now, the names of more than 125,000 detainees have been digitized, paving the way for researchers and descendants to learn more about this dark period in the nation’s history.

The names—as well as nearly 350,000 other historical documents, including camp rosters, draft cards and census forms—are now accessible on Ancestry.com. The Utah-based genealogy company has partnered with the Irei Project, a nonprofit working to memorialize Japanese American incarcerees.

The collaboration between Ancestry and the Irei Project will offer users a “longer view of family history and community history, and ultimately, American history,” says Duncan Ryūken Williams, director of the Irei Project, to the Associated Press (AP).

Born in Tokyo to a Japanese mother and British father, Williams is a Buddhist priest and a professor of religion and East Asian languages and cultures at the University of Southern California, where he also serves as the director of the university’s Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture.

Five years ago, Williams set out to not only honor Japanese American detainees, but also to correct the historical record.

In 1988, the United States issued a formal apology and sent $20,000 to more than 80,000 survivors or their descendents, for a total of $1.6 billion. But, in the years after the war, the names of many Japanese Americans had been lost or mispelled. Poor record-keeping by the U.S. government meant that no one knew exactly how many people had been detained.

Williams sought to address this erasure, beginning with accurately spellings the names of the incarcerated. Starting in 2019, he spent years poring over camp rosters and other historic documents to “properly memorialize each incarceree as distinct individuals instead of a generalized community,” per the project’s website.

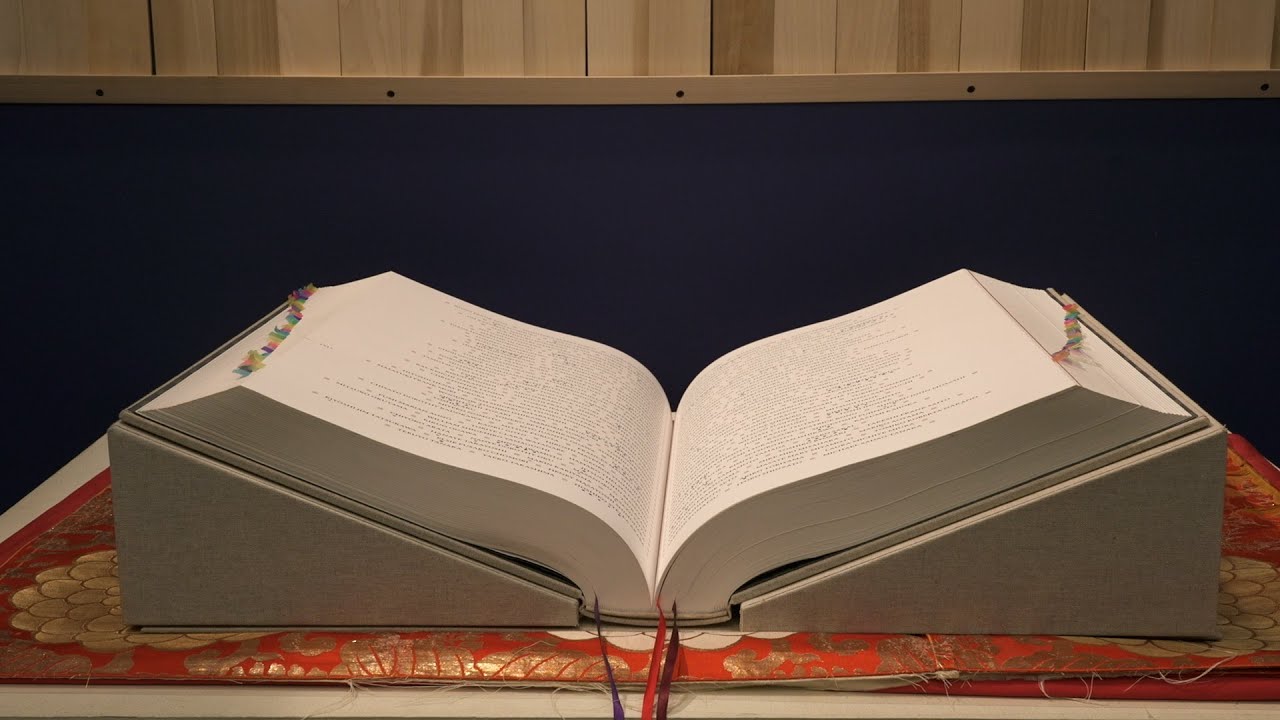

In the end, he came up with 125,284 names. He turned the list into a book and, in September 2022, delivered the 1,000-pound tome to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. The book, which serves as a monument called Ireichō, is on display at the museum through December as part of a broader “Irei: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration” exhibition. Museum-goers can make a reservation to place a stamp under names listed in the book, as a way of honoring and acknowledging individuals.

The names are also listed on the project’s website, but Williams partnered with Ancestry, which also provides access to other historic records. Williams and his team used Ancestry while verifying the spellings of the names on their list.

“Whenever there was a discrepancy in the wartime sources, our team turned to various sources found within Ancestry—principally the 1940 U.S. Census, WWII draft cards, birth and marriage certificates, as well as naturalization and social security records—to double and triple check names spellings,” Williams writes in a blog post published this week on Ancestry.com.

The project goes beyond the list of names: Starting in 2026, light sculpture monuments, called Ireihi, will be displayed on the grounds of several incarceration camps, including Amache in Colorado, which was recently made a national historic site. That same year, the Japanese American National Museum is also slated to unveil a permanent Ireihi sculpture.

“This project is not a static nor complete one,” Williams writes. “The premise of the Irei Project is that we need the public to make sure we not only remember the injustice of the incarceration, but their help in repairing the wounds of that history.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)