Queens Museum Brings Rube Goldberg Machine to Life

To celebrate an exhibition of the cartoonist and hometown hero, curators commissioned one of Rube’s overly complicated gadgets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/ab/f9ab953d-f17f-4570-94b6-fc43f43c6203/queens_rube.jpg)

When the staff at the Queens Museum learned that a traveling exhibition dedicated to Rube Goldberg was touring the country, they knew their museum needed to be a stop. They also knew the museum had to do something extra special to commemorate their hometown cartoonist, whose name has become synonymous with diagramming overly complicated solutions to common problems. So, the museum decided to bring one of Goldberg’s insane inventions to life.

The design firm Partner & Partners along with designers Greg Mihalko, Stephan von Muehlen and Ben Cohen, in turn, was commissioned to develop a real-life Rube Goldberg machine. The result—on view at the Queens Museum from October 2019 to February 2020—is what you’d imagine if you’re familiar with Goldberg’s work: visitors can press a green button, which sets an animated bird into flight. The bird then triggers an electric fan that blows a pinwheel, activating a motor that drives a boot. The boot kicks a watering can, which startles a digital cat, yada, yada, yada, until, finally, a banner falls. Subtract a few burning cigars and add in some digital updates, and it’s basically a diagram come to life.

The touring exhibition itself, called The Art of Rube Goldberg, has been going since 2017 and is the first major retrospective of the cartoonist since a 1970 exhibition at the Smithsonian. It spans his entire 72-year career. Goldberg, who was born in 1883, studied engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. But drawing was his true passion, as Emily Wilson explained previously for Smithsonian.com. After a brief stint diagramming sewers, Goldberg ditched his engineering job to illustrate a local sports paper. He eventually moved to Queens, New York, where he began drawing a series of popular, nationally syndicated comics in the late teens and early 1920s including “Boob McNutt,” “Lala Palooza” and “Foolish Questions.”

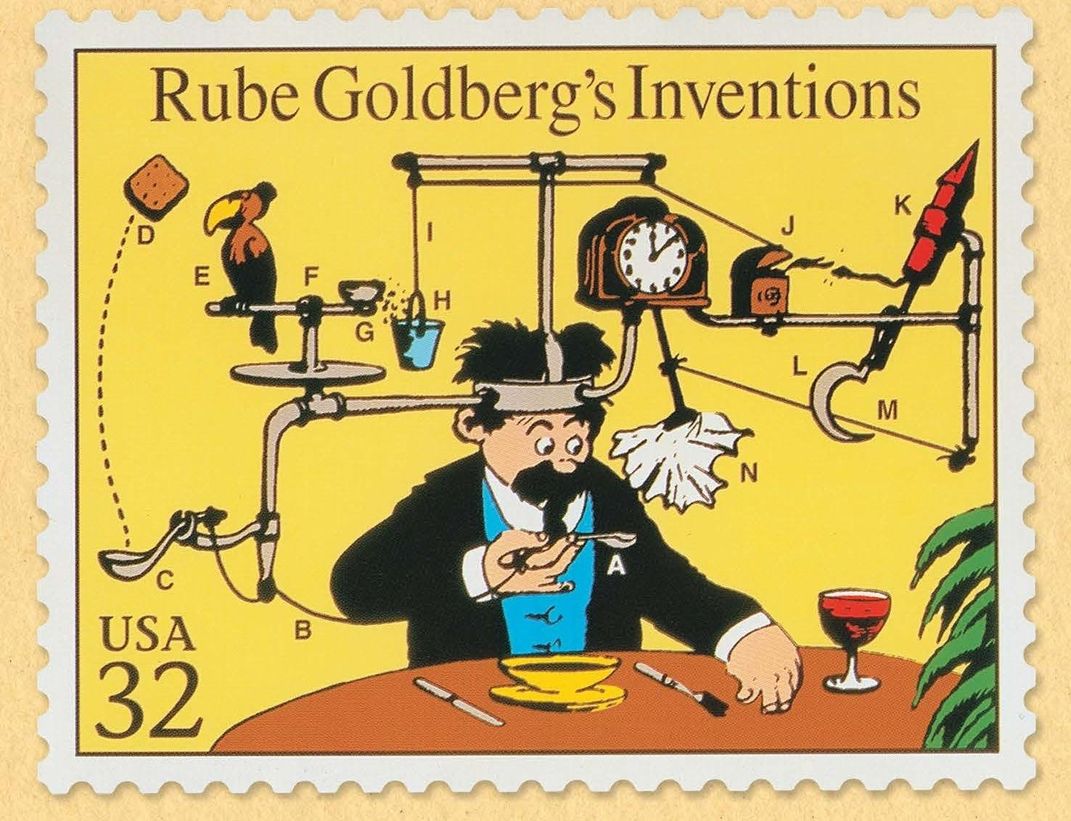

While all of them were popular—and earned Goldberg rock star status and lots of money—none was more popular than the series “The Inventions of Professor Lucifer G. Butts” in which Goldberg illustrated very complex methods for doing simple things, often involving swinging boots, springs, rockets, annoyed birds, pots and pans and lots of string. The diagrams were so popular that as early as 1931 Merriam-Webster included “Rube Goldberg” in its dictionary as an adjective meaning “accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply,” per the New Yorker.

While the inventions were more or less fun doodles, Goldberg did have a point to make, saying they were a “symbol of man’s capacity for exerting maximum effort to accomplish minimal results.”

Goldberg, who lived until 1970, had career highlights far beyond his machines. In 1930, he went to Hollywood to produce a script he’d written called Soup to Nuts which featured the debut of the Three Stooges. In 1948, he went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning. But his machines are his most lasting legacy, and remain relevant to this day.

A recent children’s book Rube Goldberg’s Simple Normal Humdrum School Day even imagines a young Rube using his fanciful machines to do everything from wake up in the morning to finish his homework. Goldberg’s estate also promotes Rube Goldberg Machine contests, in which students use everyday household objects to do the simplest tasks in the funniest way possible.

“It’s the idea of limitless possibilities to almost an absurd degree,” Sophia Marisa Lucas, curator at the Queens Museum, tells Nancy Kenney at The Art Newspaper, pinning down the lasting appeal of Goldberg's wacky inventions. “The core idea is that in pursuit of endless convenience, new languages and new sensibilities have to be orchestrated. We have to learn how to maneuver in the world differently.”