New Online Tool Reveals Raphael’s Sistine Chapel Cartoons in Stunning Detail

High-resolution scans from the V&A offer an unprecedented view of the Renaissance drawings, down to every last line and wrinkle

:focal(979x448:980x449)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/77/aa77208f-44ea-49a5-9e31-4fc185d786a1/screen_shot_2021-01-25_at_92325_am.png)

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes rank among the world’s most instantly recognizable artworks. But few know that 500 years ago, a cycle of tapestries by an equally renowned Renaissance master also adorned the Vatican City chapel’s walls. Raphael designed the works, which were created in Pieter van Aelst’s Brussels workshop between 1515 and 1521; woven with silver and gold threads, they tell stories from the lives of Saints Peter and Paul, two founding fathers of the Roman Catholic Church.

Raphael, who died in 1520 at just 37 years old, may have never seen all the completed tapestries in person. But the painter would have been intimately familiar with their “cartoons,” or preparatory drawings. As Hannah McGovern notes for the Art Newspaper, Raphael revised and finalized his designs for the tapestries on roughly 16.5- by 11.5-foot canvases, each comprised of more than 200 pieces of paper glued together.

During the 16th century, the Sistine Chapel cartoons were cut into strips and traded around Europe. The future Charles I purchased the drawings in 1623 and brought them back to his home country of England. In 1865, Queen Victoria loaned the drawings to the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert (V&A), where they have remained ever since, reported Mark Brown for the Guardian in 2019.

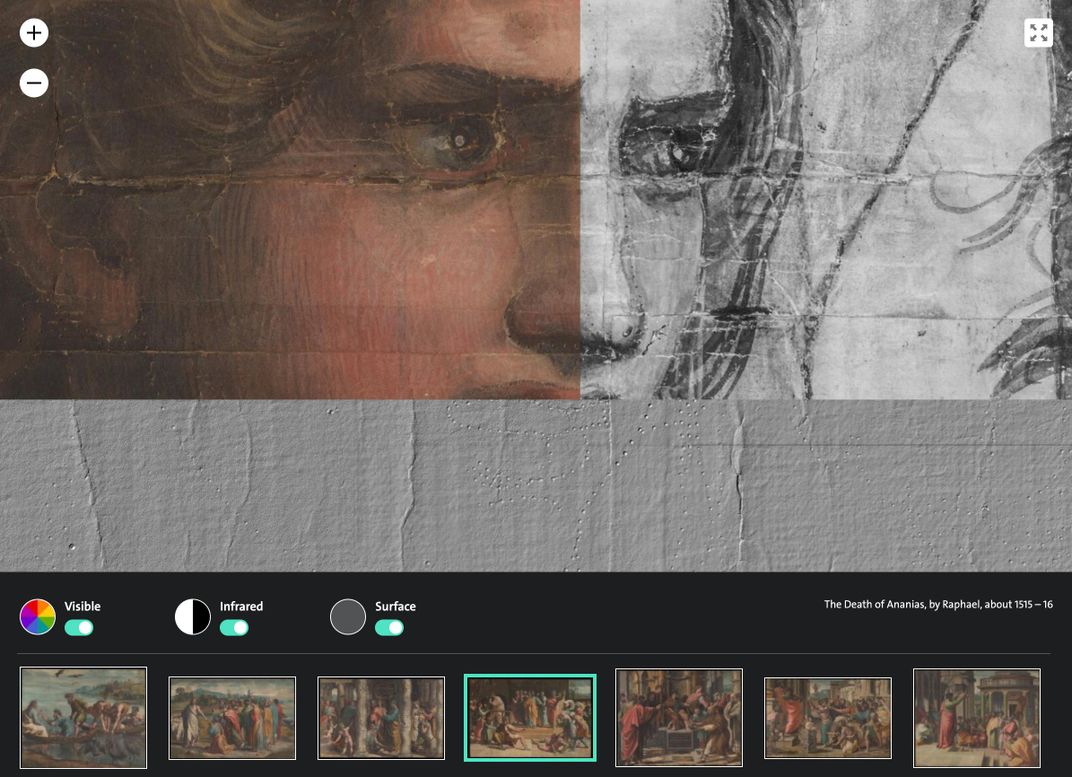

Though the London museum is currently closed due to Covid-19, art enthusiasts can now explore Raphael’s cartoons in-depth through an online V&A project, Explore the Raphael Cartoons. Complete with an essay on the works’ long history and high-resolution, interactive scans of the cartoons, the hub allows viewers to see hidden details in Raphael’s masterpieces up close.

The V&A partnered with the Factum Foundation to create the high-resolution color, infrared and 3-D scans in 2019. And last year, in honor of the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death, the museum refurbished the cartoons’ gallery, known as the Raphael Court, by repainting the walls, replacing light fixtures and taking other steps to make the cartoons “more visible and legible to in-person visitors,” as project curator Ana Debenedetti tells the Art Newspaper. (When the V&A reopens, viewers will be able to scan QR codes in the gallery to access a number of interactive features on their phones.)

Some of the scans revealed new information about the works. Compared with previous, smaller drafts of The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, for instance, new images revealed that Raphael made slight adjustments to Jesus’ forehead and eyes in his final underdrawing. The design shows Simon—who would later be renamed Peter—wearing a blue tunic and kneeling before Jesus, who has just performed a miracle.

Pope Leo X commissioned Raphael to design the silk and wool tapestries in 1515. The painter and his studio worked quickly to complete the ten cartoons, each of which depicts a different biblical scene, in just 18 months, according to the Art Newspaper.

Each tapestry design “is remarkable for the way it synthesizes a complex message, chosen to bolster papal authority, into a clear, harmonious ensemble—which Raphael had to design in reverse, as though looking at a mirror, because he knew it would be flipped on the weaver’s loom,” writes Alastair Sooke for the Telegraph.

Thanks to the online tool, viewers can zoom in on individual brushstrokes, cracks and wrinkles in the paper, charcoal underdrawings, and tiny pinpricks around the outlines of figures. Weavers made these small holes as they worked to translate Raphael’s painting into the medium of tapestry. When he was designing the work, Raphael “challenged the weavers in Brussels to, as it were, paint with threads,” says Debenedetti to the Telegraph.

The 3-D scans of the cartoons’ surfaces “take you back 500 years, when the last people to see that were Raphael and his team of apprentices,” Debenedetti tells the Art Newspaper.

She adds, “Emotionally, it’s something we’ve never been able to offer visitors before.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/56/5a56f018-efaa-4cb0-9296-1d5949d3fbe6/raphael_cartoonthe_sacrifice_at_lystra_photo_c_va_courtesy_royal_collection_trust_her_majesty_queen_elizabeth_ii_2021.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)