How the ‘Ecstatic Joy of Nature’ Unites Vincent van Gogh and David Hockney

Houston exhibition marks the first time the famed artists have been shown side by side in an American museum

:focal(832x672:833x673)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/b6/c4b6ab6b-a4ef-41e8-83f5-091d6c28bfd6/van-gogh-field-with-irises-near-arles9118916420590262027.jpg)

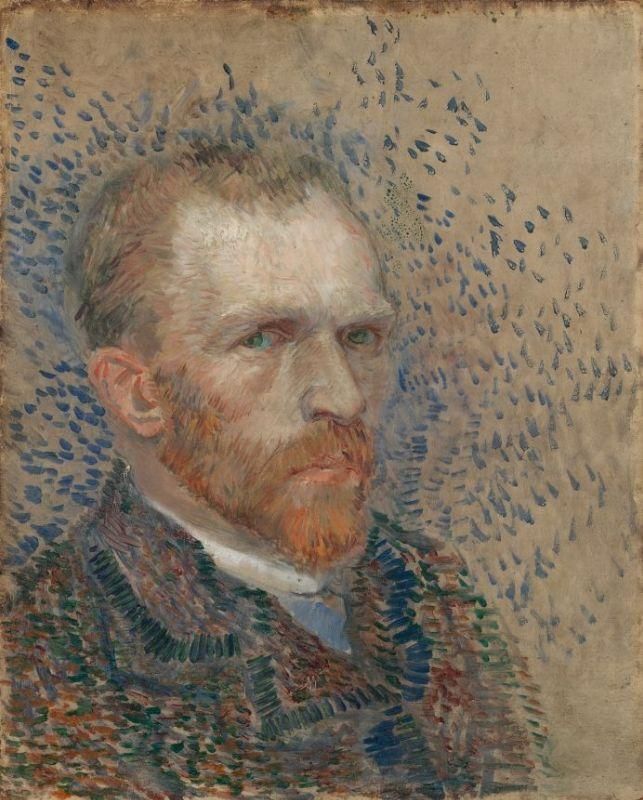

Vincent van Gogh, born in 1853, painted en plen air in French fields with globs of bright oil paint. David Hockney, born in 1937, often paints in bed on an iPad. So, what do the two artists have in common?

As a new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFAH) in Houston, Texas, demonstrates, both painters share an enduring interest in landscapes and the natural world. “Hockney–Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature,” which debuted at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2019, unites 47 of the contemporary British artist’s vibrant works with 10 by the famed Dutch Impressionist in a sweeping exploration of the pair’s connections.

Per a statement, the Houston exhibition, which runs through June 20, marks the first time the two men have been exhibited side by side in an American museum. Viewers can book advance timed tickets, in accordance with Covid-19 safety protocols, through the museum’s website.

“[What] really unites them is an absolutely ecstatic joy of nature,” curator Ann Dumas tells Architectural Digest’s Madeleine Luckel.

As winter turns to spring, the colorful landscapes featured in the exhibition “[produce] joy and delight—it’s precisely what the doctor ordered,” MFAH director Gary Tinterow tells Martin Bailey of the Art Newspaper.

In a 2019 review of the Amsterdam show, Hyperallergic’s Anna Souter likened entering the gallery to “walking into a painted fantasy forest.” In van Gogh’s wild landscapes—including the swirling, blue-hued Starry Night (1889) and the gray-green The Rocks (1888), the latter of which is featured in the exhibition—the painter plays with perspective, employing bright, jumbled color and expressive brushstrokes.

Though they lived in different eras, van Gogh profoundly influenced Hockney’s style. Hockney, a British artist who worked in Los Angeles for much of his life, returned to northeastern England in the early 2000s to care for his ailing mother and a terminally ill friend, notes the statement. There, he began painting studies of the landscapes in nearby Woldgate Woods, just as van Gogh made repeated studies of fields and trees more than a century earlier. (The bulk of the Hockney works included in this show were created during this period, between about 2004 and 2011.)

“Hockney’s admiration for van Gogh is far from incidental,” wrote Nina Siegal for the New York Times in 2019. “There are drawings in the exhibition that could have been ripped from van Gogh’s sketchbook.”

But while van Gogh sometimes painted in muted tones that reflected his somber moods, Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011, a series of massive iPad creations that chronicle the transition from winter to summer, is resplendent in neon shades of green and purple.

Siegal added, “Squint a little and one can easily mistake Mr. Hockney’s 2005 oil painting Woldgate Vista, with its layer-cake structure of wild grass, farmland, hills and sky, for van Gogh’s The Harvest of 1888.”

As Lawrence Weschler reported for Smithsonian magazine in 2013, Hockney has long embraced new technologies for art-making, displaying “an uncanny openness to technological innovation [and] eager willingness to delve into any and all manner of new gadgetry,” from fax machines to iPhones to LED stage lighting grids.

Van Gogh, meanwhile, “was constantly on the search for new ways of working, from naturalism, to Impressionism to Post-Impressionism, to add to his own style,” Edwin Becker, chief curator of exhibitions at the Van Gogh Museum, told the Times in 2019. “The same goes for Hockney, because he embraces new techniques, new developments.”

Dumas tells the Art Newspaper that Hockney continues to “[swim] against the tide in terms of conceptual art and that, like van Gogh, he still wants to immerse himself in the endless variety of the natural world.”

Van Gogh was plagued by a series of mental illnesses throughout his life. Creating art in nature became a restorative practice for the troubled artist.

“Sometimes I long so much to do landscape, just as one would for a long walk to refresh oneself, and in all of nature, in trees for instance, I see expression and a soul,” he wrote in a December 1882 letter to his brother Theo.

Closer to the end of his life, in 1888, van Gogh ruminated that “[t]he uglier, older, meaner, iller, poorer I get, the more I wish to take my revenge by doing brilliant colour, well arranged, resplendent.”

In a 2019 video interview with the Van Gogh Museum, Hockney argued that van Gogh’s love for the natural world shines through in the artist’s works, despite the difficult material conditions of his life.

“He was a kind of miserable man in a way. But when he was painting, he wasn’t,” Hockney said. “There’s love in those paintings, isn’t there? There’s not misery, there’s love.”

“Hockney–Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, through June 20.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)