Ancient Methane Explosions Rocked the Arctic Ocean at the End of the Last Ice Age

As retreating ice relieved seafloor pressures, trapped methane burst through to the water column, study says

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/7b/c77b3165-2563-4134-aa4b-9debf8202c5c/1-massivecrate.jpg)

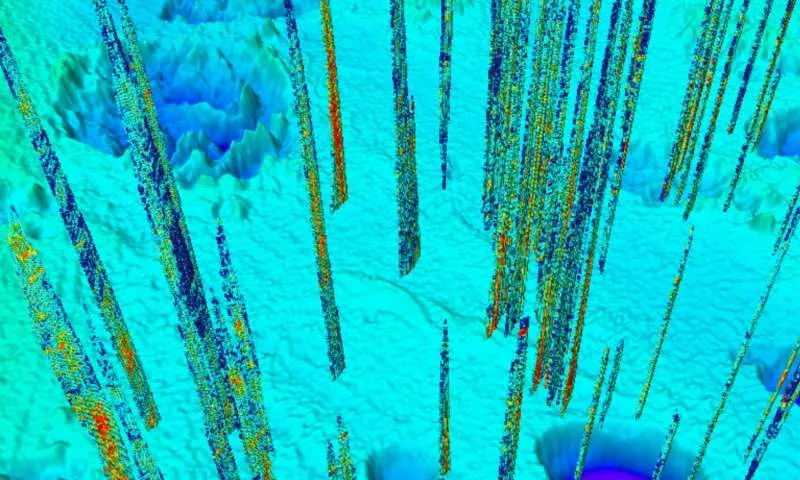

In the 1990s, researchers discovered several large craters marring the floor of the Barents Sea, the icy body of water stretching between Scandinavia, northern Russia and the Arctic circle. But recent imaging of the this region has revealed hundreds of pockmarks scattered across the sea floor. And as Chelsea Harvey reports for The Washington Post, researchers think they have figured out why: methane.

A new study, published in the journal Science, suggests that the swiss-cheese pattern of the sea floor in this region is the result of methane blowouts that occurred as glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age.

To figure this out, scientists from the CAGE Centre for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate in Norway recorded hundreds of craters in a 170-square-mile section of the Barents Sea—with over 100 measuring between 300 meters and a kilometer wide. Seismic surveys showed deep fractures that could provide a conduit for methane escape, and acoustic surveys revealed some 600 methane seeps nearby, Jeff Tollefson writes for Nature.

Using this data, the research team created a detailed simulation of how the formation and disappearance of the ice sheet would impact the area. During the Ice Age, ice sheets over a mile and a half thick covered the region, preventing the upward trickle of methane gas. The extreme pressure and cold converted this trapped gas into methane hydrates—a frozen mixture of gas and water. Hydrates can still be found at the edge of many continental shelves, Tollefson reports.

But some 15,000 years ago, the ice sheet began to melt, destabilizing the hydrates, according to the study. These frozen blobs of methane began to cluster together in mounds. As the ice continued to pull back, the ground rebounded from the released weight, placing further pressure on the growing mounds.

Eventually, the pressure was too great and the mounds exploded. “The principle is the same as in a pressure cooker: if you do not control the release of the pressure, it will continue to build up until there is a disaster in your kitchen,” Karin Andreassen lead author of the study says in the press release.

“I think it was probably like a lot of champagne bottles being opened at different times,” Andreassen tells Harvey.

Similar pockmarks have been found in many other areas across the globe. But what these ancient methane blowouts mean for past and future climate change remains unclear. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas. And retreating ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica could harbor underlying hydrocarbons. The disappearance of the ice could lead to another round of methane blowouts, which, if the gas reaches the atmosphere, could exacerbate climate change.

But as Andreassen tells George Dvorsky at Gizmodo, it’s unknown whether the methane from these ancient explosions actually made it to the surface or if it was absorbed by the water. So far researchers have not witnessed any contemporary methane blowouts, Harvey reports, and there's not enough information to guess what kind of impact they could have on climate.