Remembering the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster Ten Years Later

The 9.0-magnitude earthquake in 2011 remains the largest in Japan’s recorded history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/34/2034e4d9-6cd1-4121-85e4-e96fe4c7b3ff/gettyimages-1231646237.jpg)

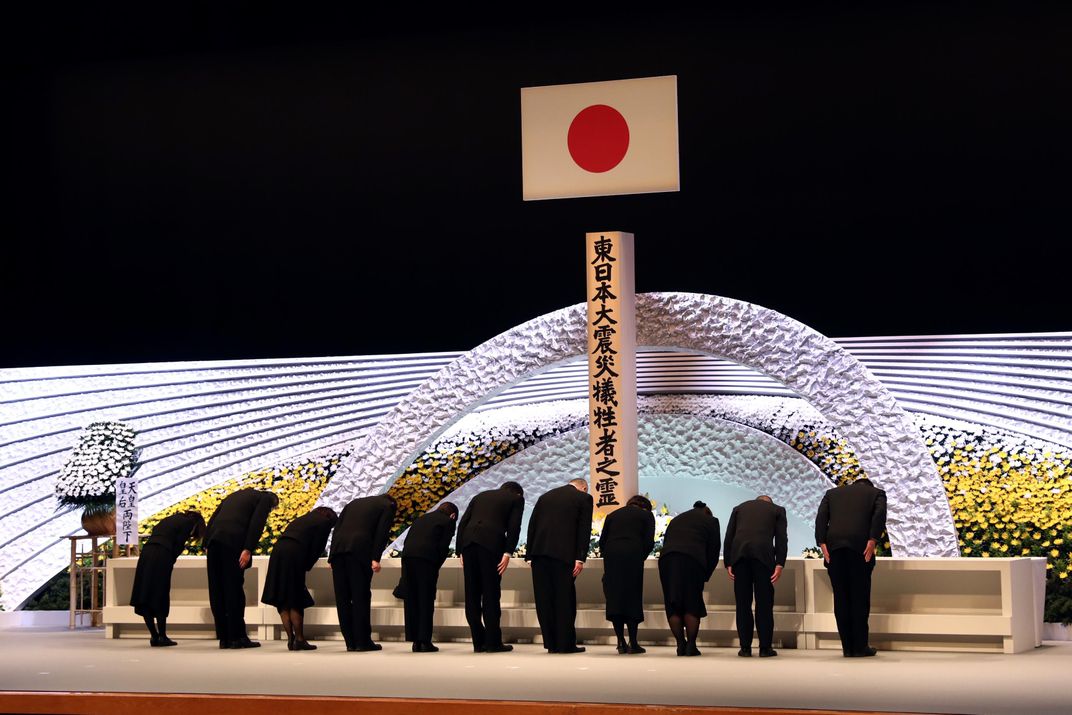

On March 11 at 2:46 p.m., residents across Japan observed a moment of silence to remember the thousands of people killed or lost when a 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck the country just one decade ago, Donican Lam reports for Kyodo News. The 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami killed 15,900 people, and subsequent deaths from illness and suicide linked to the disaster totaled 3,775. Today, about 2,500 people are still considered missing.

Anniversary memorial services in Japan were largely cancelled last year amid the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. This year, the country recognized the date with a national memorial service in Tokyo, as well as local memorials in affected regions. The ten-year anniversary also offers a milestone to revisit the progress of rebuilding the areas affected by the tsunami, including Fukushima, where the 50-foot-tall wave caused a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

Officials say that cleaning out the melted nuclear fuel from inside of the three damaged reactors could take 30 to 40 years. Critics say that timeline is optimistic, Mari Yamaguchi reports for the Associated Press.

In Ishinomaki, a city in Japan’s Miyagi Prefecture, over 3,200 people died in the disaster ten years ago, and 418 are still considered missing, Chico Harlan reports for the Washington Post.

“A lot of precious lives were lost that day, and that can never be forgotten,” said Rie Sato, whose younger sister died in the tsunami, during a memorial ceremony held on Thursday, per Kyodo News. “But I have also learned the warmness of people.”

In the last ten years, many cities that were destroyed by the tsunami have been rebuilt, including Ishinomaki. But the city’s population has declined by 20,000 people. An elementary school in Ishinomaki that caught fire during the earthquake has been preserved and will be turned into a memorial site.

The 9.0 magnitude earthquake is the biggest in the country’s recorded history, Carolyn Beeler and Marco Werman report for PRI’s The World. In order to protect the northeast region from future disasters, Japan constructed massive concrete seawalls around its coastline. Ishinomaki is also protected by an inland embankment that will be 270 miles long when construction is completed in Fukushima.

“I have seen firsthand how nature is more powerful than what humans create,” says Aya Saeki, who lives in Ishinomaki near the embankment, to PRI’s The World. “So I don’t feel entirely safe.”

At its peak, about 470,000 people had evacuated their homes after the disaster in 2011, per Kyodo News. Now, over 40,000 people still haven’t been able to return home, mostly because they lived in regions near the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant that are still considered unsafe due to radioactive contamination, per Yamaguchi in another article for the Associated Press.

When the tsunami hit the nuclear plant, the waves destroyed its power supply and cooling systems, which caused meltdowns in three reactors. Several buildings had hydrogen explosions. The melted cores of the three reactors fell to the bottom of their containment vessels, in some places mixing with the concrete foundation below, which makes their removal especially difficult, per the AP. Pandemic-related shutdowns delayed tests of a robotic arm designed to extract the melted fuel.

“Decommissioning is the most serious issue at the present,” says Kyushu University environmental chemist Satoshi Utsunomiya at to New Scientist’s Michael Fitzpatrick. “They need to remove all materials inside the damaged reactors, which is a mixture of melted nuclear fuels and structure materials emitting extremely high radiation.”

Another pressing issue is the plant’s storage of cooling water. The plant’s operator, TEPCO, says that it will run out of storage space in 2022. The water has been treated to remove almost all of the radioactive elements; only tritium, which is a version of hydrogen and can’t be removed from water because it becomes part of the water molecules, remains. While Japanese and international nuclear agencies have deemed it safe to release the cooling water into the ocean, neighboring countries and industries that rely on the ocean have pushed back against that plan, reports New Scientist.

“There is a possibility to increase the number of water tanks at the plant. But that just postpones the problem,” said Kino Masato, who works for Japan’s Ministry of Economy in the efforts to rebuild Fukushima, to local high school students last year, per Aizawa Yuko at NHK World. “The plant has a finite amount of space.”