When the Nazis Murdered Thousands by Sending Them on Forced Death Marches

Photographs, survivors’ accounts on display at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London illuminate a lesser-known chapter of WWII

:focal(403x316:404x317)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/36/223690a4-e40f-463c-81ba-f1e73aae8451/death_march.jpg)

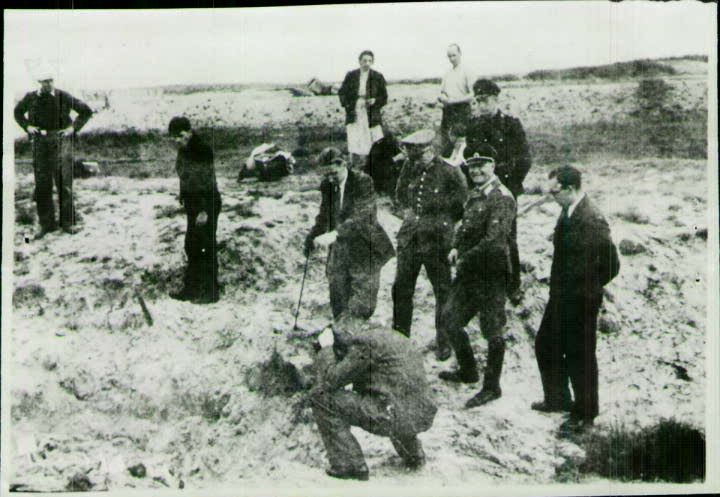

A new exhibition at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London documents the final months of the Nazis’ genocidal campaign against Europe’s Jews, when tens of thousands of people died as a result of forced marches. Titled “Death Marches: Evidence and Memory,” the display brings together images, letters and other materials that offer new insights on the end of World War II.

As Caroline Davies reports for the Guardian, the show includes clandestine photographs taken by Maria Seidenberger, a young woman who lived near the Dachau concentration camp. She secretly took pictures of a forced march from the window of her house while her mother distributed potatoes to passing prisoners.

Another set of images shows Polish Jewish sisters Sabina and Fela Szeps before and after they were sent to the Gross-Rosen network of concentration camps and forced to go on a death march.

“We have these really poignant images of the women in the ghetto, before their physical devastation,” exhibition co-curator Christine Schmidt tells the Guardian. “And then images of them in May 1945, after liberation. And they are completely emaciated, completely physically devastated. One died the day after the photograph was taken. You can just see the incredible physical toll.”

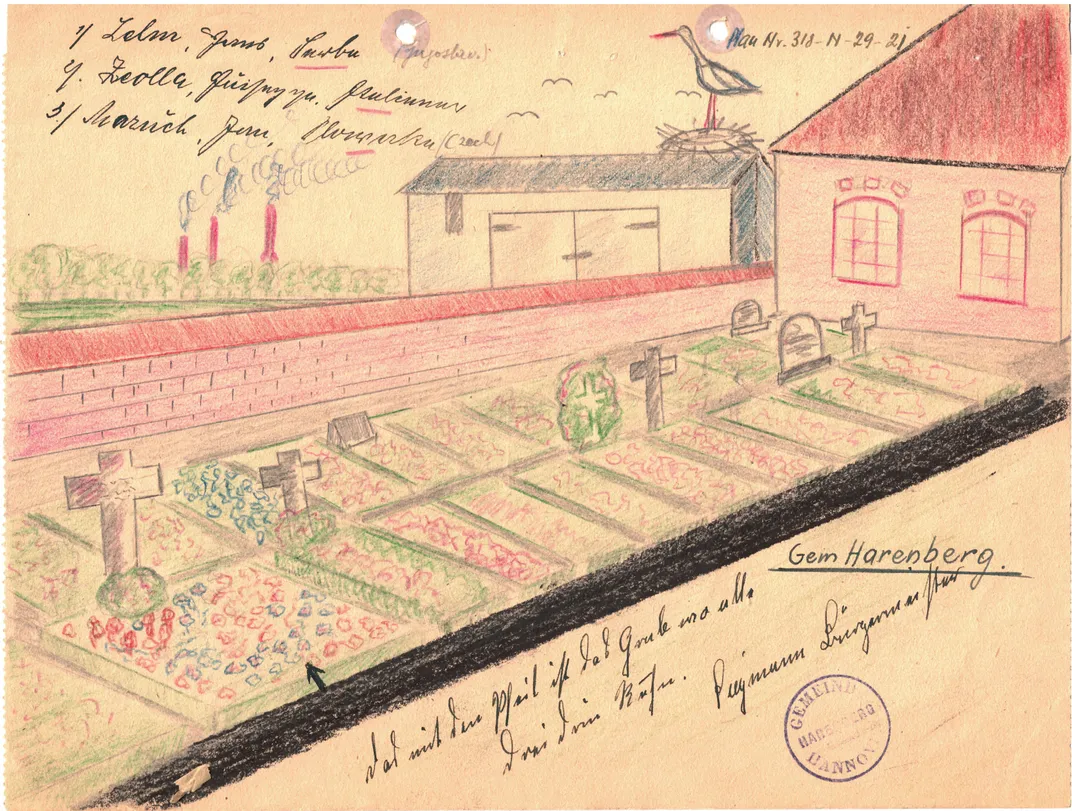

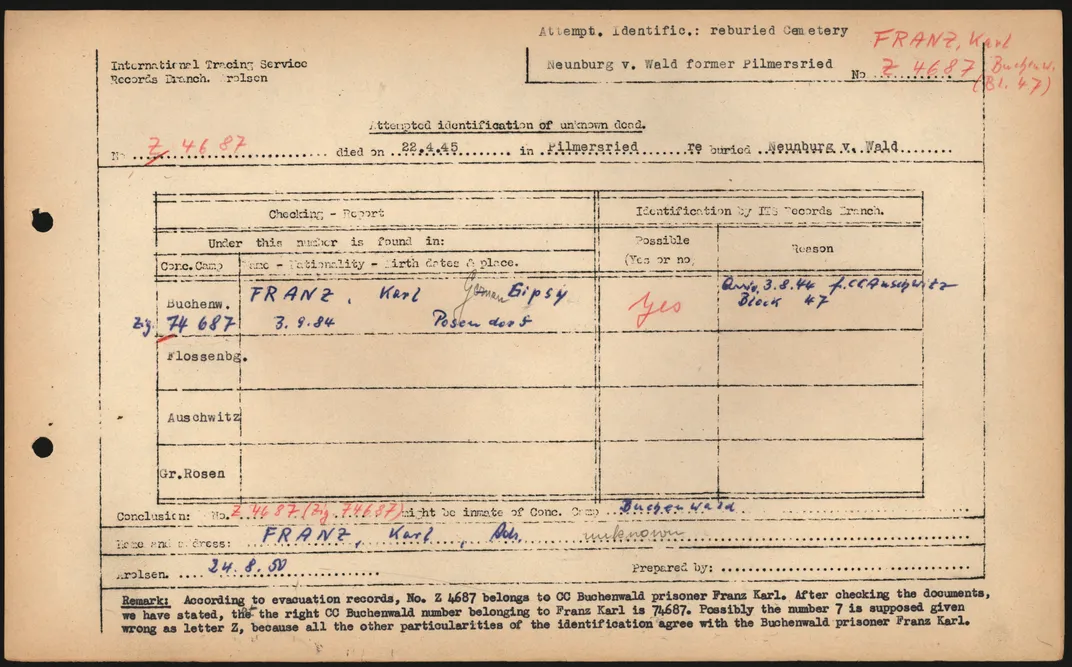

Per a statement, the exhibition examines how researchers gathered forensic evidence and otherwise documented the death marches in the aftermath of the Holocaust.

“The people who had survived, civilian witnesses who saw what happened, and victims’ bodies that had been recovered form the basis of evidence of what we know today about the death marches,” writes Schmidt for the Jewish Chronicle.

“Death Marches” features a rich collection of accounts from survivors, including Hungarian woman Gertrude Deak, who describes being forced to walk barefoot through the snow with no food.

“[T]he guards shot anybody who stopped for lack of strength,” Deak recalled in her testimony. “Occasionally they would let us rest for [two] hours and then on again. In that most terrible conditions we still could rejoice, when the Americans with their ‘planes dived down and with precision would shoot upon the German guards.”

Deak, later known as Trude Levi, went on to work for the Wiener Library. As Harry Howard reports for the Daily Mail, her memoir, A Cat Called Adolf, is also part of the exhibition,

Per the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, death marches began after Soviet forces captured Lublin/Majdanek in July 1944—the first Allied liberation of a major concentration camp. Because the SS had not dismantled the camp, Soviet and Western media were able to use footage of the camp and interviews with survivors to reveal Nazi atrocities to the world.

In response to this unwelcome exposure, SS head Heinrich Himmler ordered the forced evacuation of prisoners toward the center of Nazi territory. Besides hiding the camps from the world, Himmler believed this move would allow prisoners to continue their forced labor for the Nazis. He also hoped that Germany could use the inmates as hostages in peace negotiations with the Allies.

While initial evacuations of the camps took place by train or ship, by the winter of 1944 and 1945, the Allies’ air bombing had made this largely impossible, forcing evacuations to continue on foot.

SS guards shot thousands of people who couldn’t keep going on the forced marches; many others died of hunger and exposure. As the Sydney Jewish Museum’s Holocaust portal notes, the SS removed almost 60,000 prisoners from Auschwitz in January 1945, with more than 15,000 dying as they marched through the frigid Polish winter.

A few days later, guards began marching almost 50,000 prisoners from the Stutthof camp to the Baltic Sea coast. More than half died—some of them forced into the water and then murdered with machine guns. Marches continued until shortly before the German surrender on May 7, 1945, with prisoners in Buchenwald and Dachau forced on death marches in April.

During the 1950s and ’60s, the Wiener Holocaust Library collected more than 1,000 accounts from Holocaust survivors. The London institution is now in the process of translating and digitizing these documents. In addition to forming part of the library’s exhibitions, about 400 of the accounts are available online in the Testifying to the Truth archive. Accounts of the death marches make up just a small part of the collection.

“There weren’t that many survivors of the death marches, so these testimonies we have are rare, and are quite precious documents,” Schmidt tells the Guardian. “This vast, chaotic period is a story that isn’t often told.”

“Death Marches: Evidence and Memory” is on view at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London through August 27. Visitors must pre-book tickets and follow Covid-19 safety precautions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)