Around 1568, Florentine nun Plautilla Nelli—a self-taught painter who ran an all-woman artists’ workshop out of her convent—embarked on her most ambitious project yet: a monumental Last Supper scene featuring life-size depictions of Jesus and the 12 Apostles.

As Alexandra Korey writes for the Florentine, Nelli’s roughly 21- by 6-and-a-half foot canvas is remarkable for its challenging composition, adept treatment of anatomy at a time when women were banned from studying the scientific field, and chosen subject. During the Renaissance, the majority of individuals who painted the biblical scene were male artists at the pinnacle of their careers. Per the nonprofit Advancing Women Artists organization, which restores and exhibits works by Florence’s female artists, Nelli’s masterpiece placed her among the ranks of such painters as Leonardo da Vinci, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Pietro Perugino, all of whom created versions of the Last Supper “to prove their prowess as art professionals.”

Despite boasting such a singular display of skill, the panel has long been overlooked. According to Visible: Plautilla Nelli and Her Last Supper Restored, a monograph edited by AWA Director Linda Falcone, Last Supper hung in the refectory (or dining hall) of the artist’s own convent, Santa Caterina, until the house of worship’s dissolution during the Napoleonic suppression of the early 19th century. The Florentine monastery of Santa Maria Novella acquired the painting in 1817, housing it in the refectory before moving it to a new location around 1865. In 1911, scholar Giovanna Pierattini reported, the portable panel was “removed from its stretcher, rolled up and moved to a warehouse, where it remained neglected for almost three decades.”

Plautilla’s Last Supper remained in storage until 1939, when it underwent significant restoration. Returned to the refectory, the painting sustained slight damage during the momentous flooding of Florence in 1966 but escaped largely unscathed. Upon the refectory’s reclassification as the Santa Maria Novella Museum in 1982, the work was transferred to the friars’ private rooms, where it was kept until scholars intervened in the 1990s.

Now, for the first time in some 450 years, Nelli’s Last Supper—newly restored following a four-year campaign by AWA—is finally on public view. No longer consigned to Santa Maria Novella’s private halls, the work is installed in the church’s museum, where it hangs alongside masterpieces by the likes of Masaccio and Brunelleschi.

According to a press release, AWA raised funds for the project through crowdfunding and a donation-based “Adopt an Apostle” program. The Florentine nonprofit’s all-woman team of curators, restorers and scientists then began the arduous process of restoration, performing tasks including removing a thick layer of yellow varnish, treating flaking paint and conducting an analysis of the pigments’ chemical composition.

“We restored the canvas and, while doing so, rediscovered Nelli’s story and her personality,” lead conservator Rossella Lari says. “She had powerful brushstrokes and loaded her brushes with paint.”

Given the fact that reflectography found little evidence of under-drawing, Lari adds, it’s clear the nun-turned-artist “knew what she wanted and had control enough of her craft to achieve it.”

Nelli, born into a Florentine merchant family in 1524, joined the Dominican Santa Caterina convent at age 14. Per Financial Review’s Nicky Lobo, she began her artistic career by making miniature copies in the style of Renaissance master Fra Bartolomeo. Soon, the self-taught artist found herself in high demand, garnering private devotional commissions from the city’s wealthy families.

As one of just four women cited in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Nelli commanded more attention than the majority of her female peers. In fact, the biographer wrote, “There were so many of her paintings in the houses of gentlemen in Florence, it would be tedious to mention them all.”

Nelli’s status as a nun enabled her to pursue art at a time when women were all but banned from the profession. According to Artsy’s Karen Chernick, Renaissance nunneries “extracted women” from domestic duties such as marriage and motherhood, freeing them to engage in otherwise off-limits activities.

“We think of these nuns as imprisoned, but it was a very enriching world for them,” AWA Director Linda Falcone tells Chernick.

Renaissance women “could obviously paint as part of their cultural education,” Falcone says, “but the only way they could paint large-scale works and get public commissions was through their convent.”

Most paintings produced by Nelli and her workshop of some eight fellow nuns were smaller devotional works made for outside collectors. But some canvases—including Last Supper and others designed for private use within the convent—were monumental, requiring expensive scaffolding and assistants that the nuns paid for with funds from their commissions.

Per the AWA statement, the newly restored work was created in true “workshop style”—in other words, different artists of varying levels of expertise contributed to the religious scene.

As Chernick reports in a separate Atlas Obscura article, Nelli chose to depict Jesus and his 12 apostles dining on fare typically enjoyed by the residents of Santa Caterina. In addition to traditional wine and bread, she included a whole roasted lamb, lettuce heads and fava beans. And unlike Last Supper scenes painted by male artists, AWA founder Jane Fortune pointed out in a 2017 essay for the Florentine, Nelli’s tableware is incredibly elaborate; among the items on display are turquoise ceramic bowls, fine china platters and silver-adorned glasses.

According to historian Andrea Muzzi, Last Supper builds on the style established by Leonardo da Vinci’s similarly themed work. This monumental fresco, painted for the refectory of Milan’s Santa Maria delle Grazie between 1495 and 1498, was so influential, Muzzi writes in her essay “A Nun Who Paints,” that the “sacred subject could no longer be represented without his work being taken into account.” An apostle painted fourth from the left in Nelli’s version, for example, gestures with open hands in a manner reminiscent of Leonardo’s composition.

For Financial Review, Lobo paints an apt portrait of Nelli’s singular skill: “Picture the nun in her holy garments, mixing her pigments and stepping up onto scaffolding to brush enormous strokes of paint onto a canvas taller than her and wider than a contemporary billboard,” he writes. “The physical undertaking would have been immense, requiring great strength, focus and discipline—to say nothing of the will required to take on this sacred subject attempted before only by the male greats.”

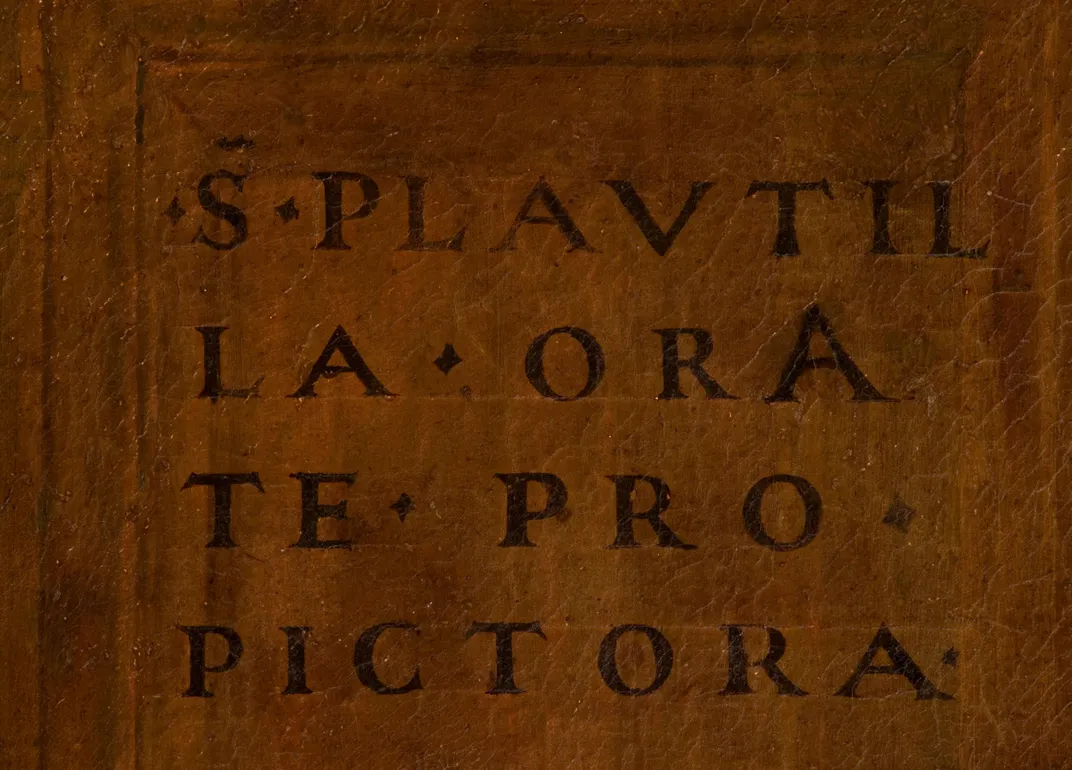

An inscription hidden in the upper left corner of the painting suggests Nelli was keenly aware of the landmark nature of her creation. Written in Latin, it bears the artist’s name (an unusual declaration of authorship for the period) and a poignant appeal to the viewer: “Orate pro pictora,” or “Pray for the paintress.”

:focal(3492x685:3493x686)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/21/2e21d7dd-b15e-44fe-96e4-9a59205b7f4c/plautilla_nelli_08.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)