Fragments of Ancient Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead’ Reunited After Centuries

Researchers in Los Angeles realized that a linen wrapping housed in the Getty’s collections fit perfectly with a piece held in New Zealand

:focal(713x506:714x507)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/3a/bf3a4c0b-77fb-47da-888f-cb896e8c8ec4/book_of_the_dead_egypt.jpeg)

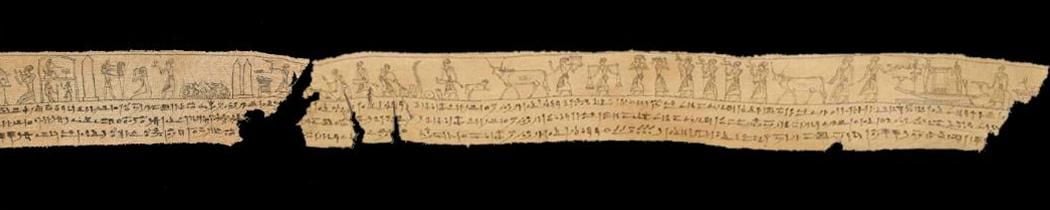

Archaeologists have digitally reunited two fragments of a 2,300-year-old linen mummy wrapping covered in hieroglyphics from the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead.

As Laura Geggel reports for Live Science, researchers from the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities at the University of Canterbury (UC) in New Zealand had cataloged a 2- by 19-inch portion of the scroll in an online database. When employees from the Getty Research Institute (GRI) in Los Angeles saw photographs of the digitized wrapping, they realized that a section housed in their collections fit perfectly with the UC scrap.

“There is a small gap between the two fragments; however, the scene makes sense, the incantation makes sense, and the text makes it spot on,” says Alison Griffith, a classics scholar at UC, in a statement. “It is just amazing to piece fragments together remotely.”

Both segments contain excerpts from the Book of the Dead, which was thought to help the deceased navigate the afterlife. Per the statement, the pieces are written in a hieratic, or cursive, script and date back to 300 B.C.

“Egyptian belief was that the deceased needed worldly things on their journey to and in the afterlife, so the art in pyramids and tombs is not art as such, it’s really about scenes of offerings, supplies, servants and other things you need on the other side,” Griffith explains.

The digitally reunited portions came from a series of bandages once wrapped around a man named Petosiris, reports Artnet News. Fragments of the linen are scattered across museums and private collections around the globe.

“It is an unfortunate fate for Petosiris, who took such care and expense for his burial,” says Foy Scalf, head of research archives at the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, in the statement.

How the UC and Getty pieces got separated is unclear, but the team has already located another possible missing fragment at the University of Queensland, Australia. The UC segment, for its part, originated in the collection of Charles Augustus Murray—the British consul general in Egypt from 1846 to 1853—and later became the property of British official Sir Thomas Phillips. The university acquired the linen at a Sotheby’s sale in London in 1972.

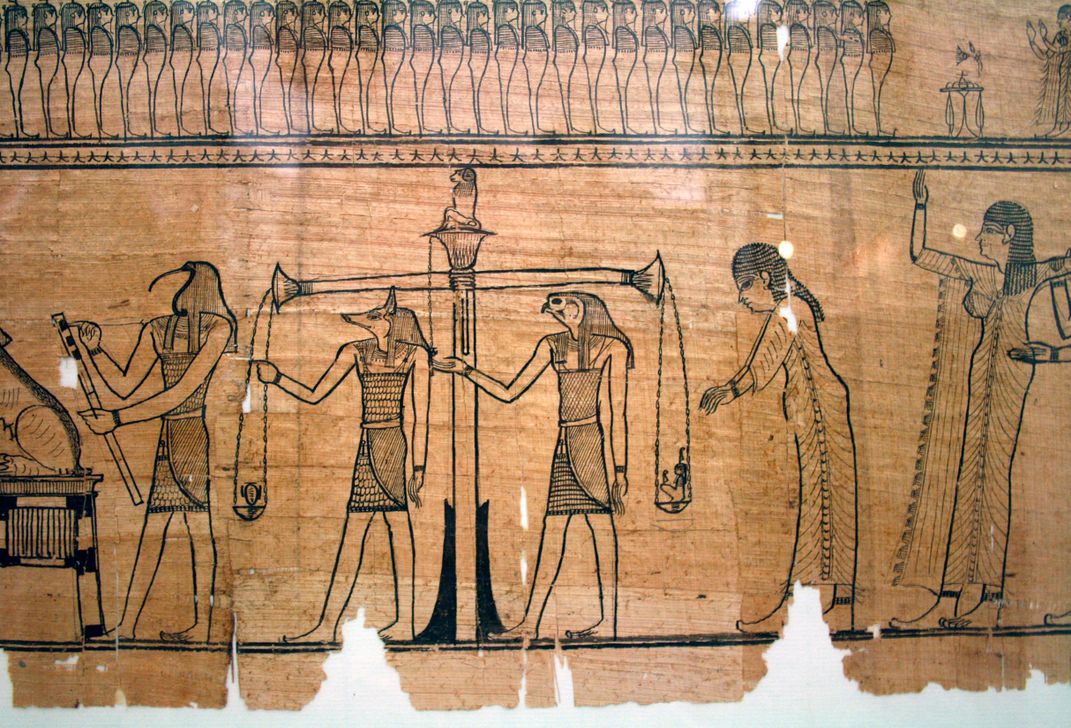

Petosiris’ burial wrappings depict butchers dismembering an ox as an offering; people transporting furniture for use in the afterlife; a funerary boat with the goddesses Isis and Nepthys on either side; and a man pulling a sledge featuring a likeness of Anubis, god of mummification and the afterlife. As Griffith says in the statement, a scribe (or scribes) meticulously penned these hieroglyphics with “a quill and a steady hand.”

According to Kellie Warren of the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), different tombs featured distinct iterations of the Book of the Dead, but certain images—like the gods weighing the deceased person’s heart against a feather—recurred regularly.

Ancient Egyptian funerary texts first appeared on tomb walls during the Old Kingdom period (around 2613 to 2181 B.C.). Initially, only royalty at the ancient necropolis of Saqqara could have these so-called Pyramid Texts inscribed at their graves; per Encyclopedia Britannica, the oldest known Pyramid Texts appear on the tomb of Unas, the last king of the fifth dynasty.

Over time, Egyptian funerary customs changed, with versions of the Coffin Texts—a later adaptation of the Pyramid Texts—appearing on the sarcophagi of nonroyal people, including nobles, notes ARCE. During the New Kingdom period (roughly 1539 to 1075 B.C.), the Book of the Dead became available to all who could afford a copy and, by extension, gain access to the afterlife.

Scholars hope that the newly joined fragments will reveal more information about ancient Egyptian funerary practices.

“The story, like the shroud, is being slowly pieced together,” says Terri Elder, a curator at the Teece Museum, in the statement.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)