Researchers Use Particle Accelerator to Peek Inside Fossilized Poop

This new method could reveal just what dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures ate

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/e7/64e78e5e-eac5-4269-9111-c5352ed1ffa2/coprolite.jpg)

Scientists study every inch of an animal—from the tip of their nose right down to their, well, poop. And the same goes for ancient creatures. But until now, only a limited amount could be learned from from studying fossilized feces, also known as coprolites. As Ryan F. Mandlebaum reports for Gizmodo, scientists recently turned to a synchrotron particle-accelerator for help discerning every morsel of data locked inside the prehistoric poop.

Their study, published this week in the journal Scientific Reports, documents a new method to examine the treasures hidden within the coprolite without destroying the samples. These ancient turds are actually troves of information. Due to their phosphate-rich chemistry, poop can actually preserve many delicate specimens, such as muscle, soft tissue, hair and parasites.

But accessing all those bits and pieces usually means cutting the fossil into thin slices and examining it under different microscopes, a process that not only destroys part of the fossil but may not reveal all the minute details. In recent years, some researchers have begun examining coprolites using CT scans, which produce three-dimensional images of their innards, but those often produce poor contrast images.

So Martin Qvarnström, lead author on the study, and his team from Sweden’s Uppsala University began searching for a solution. The team took a pair of 230-million-year-old coprolites from Poland to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, to try to get a look inside, using a technique with a frighteningly long name: propagation phase-contrast synchrotron microtomography.

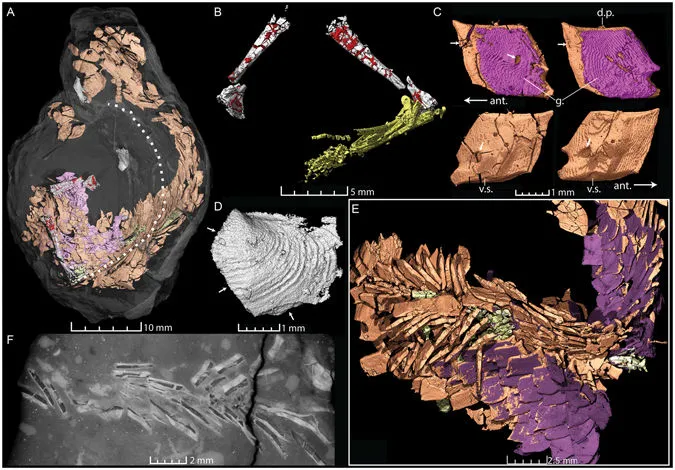

In essence, the circular half-mile particle accelerator strikes the coprolite with x-rays thousands of times stronger than a CT scan, allowing the researchers to build an incredibly detailed 3D model of the interior of the fossil.

The experiment worked. In one coprolite the researchers found the remains of three beetle species, including two wing cases and a part of a leg. The other specimen contained crushed clam shells and pieces of a fish. The researchers believe that hunk of poop came from a large lungfish, the fossil of which was found near the coprolite.

“We have so far only seen the top of the iceberg” Qvarnström says in a press release. “The next step will be to analyze all types of coprolites from the same fossil locality in order to work out who ate what (or whom) and understand the interactions within the ecosystem.”

The technique could help coprolites take center stage in paleontology, much as other trace fossils like dinosaur footprints and fossilized vomit has become increasingly important in recent years. “Analyzing coprolites at this level of detail opens up an entire new universe of research possibilities for those interested in reconstructing the paleobiology of extinct organisms,” NYU anthropology professor Terry Harrison tells Mandelbaum. In other words, this new method provides quite the dump of information.