Revisiting the Artistic Legacy of Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock’s Wife

A London retrospective unites almost 100 of the genre-bending artist’s works

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/4f/cd4f2f5d-b13d-4bab-8afc-5460f556ffce/krasner-exhibition-2310g.jpg)

Lee Krasner was a constant innovator, going so far as to cut up and recycle earlier works that no longer met her high standards. She embraced the Cubist style popularized by Pablo Picasso, the “all-over” approach of Abstract Expressionism and the colorful form of collage seen in Henri Matisse’s late-career creations—but her versatility was long overlooked by the art world, which too often classified her as a fringe character in American Abstract Expressionist circles, better known as the dutiful wife of Jackson Pollock.

An upcoming exhibition at London’s Barbican Art Gallery strives to reframe Krasner's image, drawing on almost 100 works to trace the trajectory of her boundary-pushing, 50-year career. Titled Lee Krasner: Living Colour, the retrospective features early self-portraits, charcoal life drawings, large-scale abstract paintings, collages and selections from the famed “Little Images” series.

Born to Russian immigrants in 1908, Krasner decided to become an artist at age 14, enrolling in the only local art course open to girls at the time. As exhibition assistant Charlotte Flint writes in a Barbican blog post, the young Brooklyn native quickly abandoned traditional styles, opting instead for the bold modern movements pioneered by Picasso, Matisse and similarly avant-garde artists.

“Known for her fiercely independent streak, Krasner was one of the few women to infiltrate the New York School in the 1940s and ’50s,” writes Meredith Mendelsohn in an Artsy editorial. Krasner, already an established figure in the local art scene, met her future husband at a 1941 exhibition where both had works on view. The pair married in October 1945 and soon moved to a rural East Hampton farmhouse where they could better focus on their craft. While Pollock was busy creating his characteristic panoramic drip paintings, she was focused on producing her kaleidoscopic canvases.

According to the Guardian’s Rachel Cooke, the couple was estranged by the time of Pollock’s fatal 1956 car crash. After a day of drinking, the artist infamously lost control of the wheel, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a receptionist to Ruth Kligman (a painter and Pollock’s mistress at the time), upon impact; Kligman, who was also in the car, miraculously survived the crash.

Following Pollock’s death, Krasner moved into his studio—“there was no point in letting it stand empty,” she later said—and began crafting enormous paintings that required her to leap across the barn while wielding a long-handled brush ideal for maneuvering into distant corners.

“It was almost as if she had unfolded herself,” Cooke writes. “Henceforth, she could work on an unprecedented scale.”

According to Artsy’s Mendelsohn, Krasner’s “Umber Paintings”—also known as “Night Journeys,” the neutral-toned canvases date to between 1959 and 1962—marked a turning point in her career. Plagued by insomnia linked with Pollock’s death and her mother’s subsequent death in 1959, Krasner shifted styles, producing paintings with what art historian David Anfam calls a previously unseen “degree of psychological intensity” marked by “emotive scale and fierce movement.” Crucially, these works, rendered in chaotic swirls of brown, cream and white, differed dramatically from the abstract Color Field paintings popular at the time. Unlike the muted, serene canvases of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, Krasner’s latest creations were gestural, overtly aggressive in a manner suggestive of her deceased husband’s drip paintings.

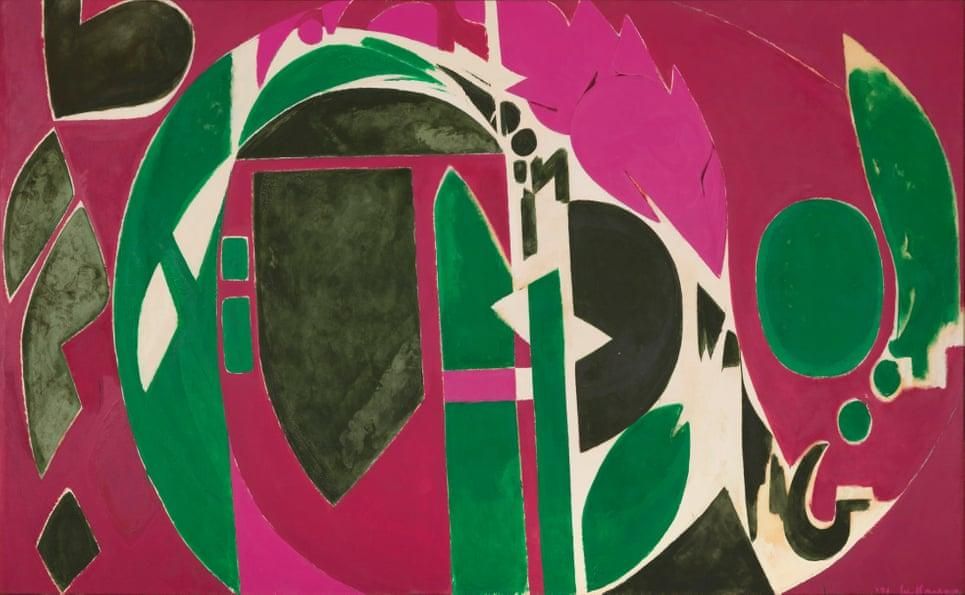

Following the “Umber Paintings,” Krasner returned to the world of vibrant colors—a move demonstrative of her willingness to reinvent.

“The fixed image terrified her,” curator Eleanor Nairne tells Sotheby’s Joe Townend. “She felt that it was an inauthentic gesture to think that some singular imagery could contain everything that she was as a person. She went through these cycles of work and these rhythms, and it was often a very painful process.”

Throughout her career, Krasner often returned to earlier works. Rather than admiring her past accomplishments, however, she completely changed them, cutting and reorganizing fragments to create new pieces.

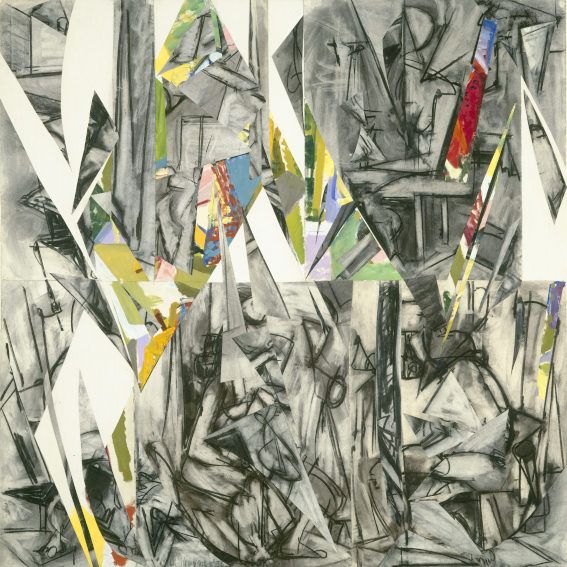

An untitled neo-Cubist work created in 1984, the year of her death, perhaps best epitomizes Krasner’s constant demand for reinvention. As IdeelArt’s Phillip Barcio writes, the canvas (her last known work) blends painting, charcoal drawing and collage, synthesizing the many mediums the artist used over her life in a “single, profound, elegant statement.”

Lee Krasner: Living Colour is on view at London’s Barbican Art Gallery from May 30 through September 1, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)