Ruins of Monumental Church Linked to Medieval Nubian Kingdom Found in Sudan

The building complex was likely the seat of Christian power for Makuria, which was once as large as France and Spain combined

:focal(579x455:580x456)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/6c/bd6c737e-c180-40b0-ad0a-588015546698/nubian_church.jpg)

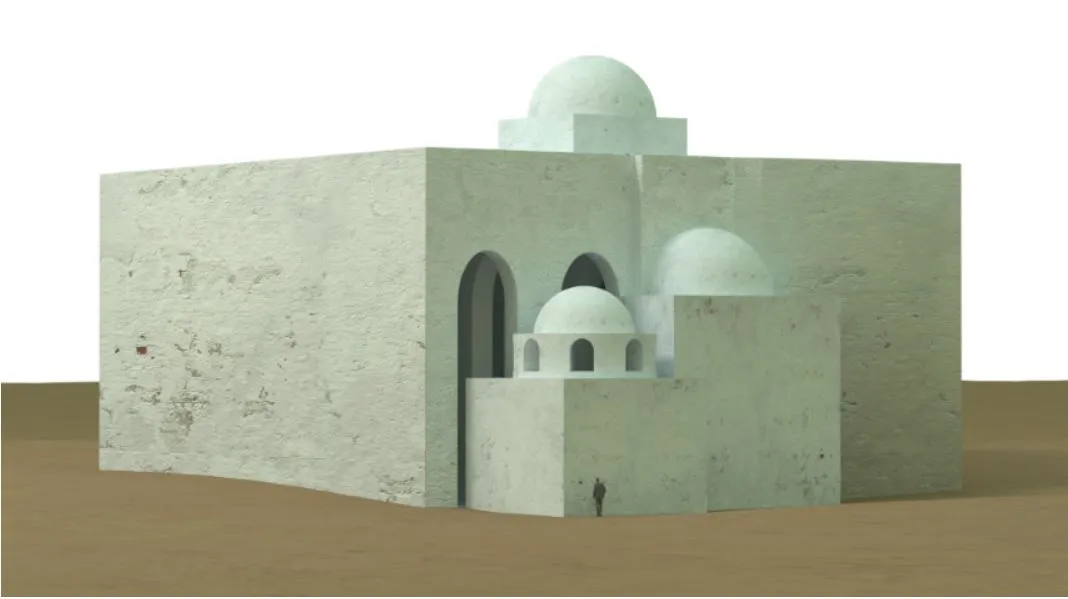

Archaeologists in northern Sudan have discovered the ruins of a cathedral that likely stood as a seat of Christian power in the Nubian kingdom of Makuria 1,000 years ago.

As the Art Newspaper’s Emi Eleode reports, the remains, discovered in the subterranean citadel of Makuria’s capital city, Old Dongola, may be the largest church ever found in Nubia. Researchers say the structure was 85 feet wide and about as tall as a three-story building. The walls of the cathedral’s apse—the most sacred part of the building—were painted in the 10th or early 11th century with portraits believed to represent the Twelve Apostles, reports Jesse Holth for ARTnews.

“Its size is important, but so is the location of the building—in the heart of the 200-hectare city, the capital of the combined kingdoms of Nobadia and Makuria,” says archaeologist Arthur Obluski, director of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology (PCMA) at the University of Warsaw, which conducted the excavation, in a statement.

The team found the site in February with the help of remote sensing technology. But as Obluski tells the Art Newspaper, he and his colleagues had “not expected to find a church but rather a town square which could have been used for communal prayers.” Previously, researchers had believed that a church outside the city walls served as Old Dongola’s cathedral.

Just east of the church apse, the archaeologists found the dome of a large tomb. The layout mirrors that of the Cathedral of Faras, another Nubian city located north of Old Dongola near the modern border of Sudan and Egypt. But the dome in the newly discovered complex is much larger—about 24 feet in diameter, compared with the Faras tomb, which measures only about 5 feet in diameter. Extrapolating from the tomb in Faras, which belonged to Joannes, the bishop of Faras, Obluski says the Old Dongola tomb may be that of an archbishop.

Salim Faraji, a scholar of medieval Nubia at California State University, Dominguez Hills, who was not involved in the excavations, tells Atlas Obscura’s Matthew Taub that the discovery “is not surprising at all considering that Old Dongola was the seat of a powerful Christian kingdom in Medieval Nubia that conducted foreign diplomacy with Muslim Egypt, Byzantium, and the Holy Roman Empire.”

Per World History Encyclopedia, the kingdom of Makuria was a great power in the region between the 6th and 14th centuries A.D. Old Dongola, located on the Nile River, grew into a significant city starting in the sixth century. Its residents used water wheels to irrigate land for agriculture. Following a 652 truce known as the Baqt, the Christian kingdom enjoyed a mostly peaceful six-century relationship with Egypt. Muslims were given protection when passing through the kingdom and allowed to worship at a mosque in Old Dongola. Along with Egypt, Makuria traded with the Byzantine Empire and Ethiopia.

Obluski tells Atlas Obscura that Makuria was a “fairy tale kingdom” that has now been largely forgotten. At its peak, it was as large as Spain and France combined; Old Dongola was as big as modern Paris at one point. The kingdom “stopped advances of Islam in Africa for several hundred years,” even while Muslims “conquered half of the Byzantine Empire,” Obluski adds.

Among Old Dongola’s best-known Makurian-period sites is the Throne Hall, a royal building later converted into a mosque. Archaeologists have also found large villas that belonged to state and church officials. The city was home to dozens of churches whose interior walls were painted with frescoes, some of which are now on display at the National Museum in Khartoum. Old Dongola is also known for the beehive-shaped Islamic tombs built after the Mamluks of Egypt took over the area in the early 14th century.

Researchers are now working with an art conservation and restoration team to secure the church’s paintings and eventually prepare them for display.

“In order to continue the excavations, the weakened and peeling wall plaster covered with painting decoration must be strengthened, and then carefully cleaned of layers of earth, dirt and salt deposits that are particularly harmful to the wall paintings,” says Krzysztof Chmielewski, who is leading the conservation effort for the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, in the statement. “When a suitable roof is erected over this valuable find, it will be possible to start the final aesthetic conservation of the paintings.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)