Sail-Powered Ships Are Making a Comeback

New pressures have engineers turning to old ideas, and Rolls-Royce is working on a sailing ship

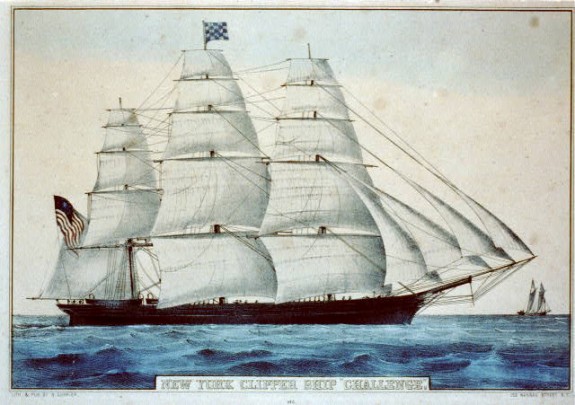

A c 1835 lithograph of the clipper ship Challenger. Photo: Library of Congress

“Clipper ships were not a specific design, they were a state of mind,” says John Lienhard, an engineer from the University of Houston. “And that state of mind lasted only a decade.”

Bristling with a staggering array of sails and built for speed, clipper ships were the “greyhounds of the sea.” And now, because of rising fuel costs and limits on gas emissions, says Businessweek, clippers—sails and all—may be on their way back.

Rolls-Royce Holdings is best known for producing engines that powered planes from the late Concorde to the current Airbus superjumbo. Now the British propulsion giant is working with partners to develop a modern-day clipper ship, as it bets that regulations curbing air pollution emissions will increase fuel costs for conventional ocean freighters and herald a New Age of Sail.

In the mid-19th century, says Lienhard, soaring prices for cargo shipping made it more profitable for vessels to be swift instead of bulky—a change that drove the temporary reign of clippers.

So masts rose into the sky. Hulls developed a knife-edged bow. And the widest beam was moved over half-way back. Economy and long life were literally thrown to the winds. Ships began to look like they’d sailed out of a child’s dream. They were tall and beautiful. Acres of canvas drove them at 14 knots.

The ships, says the Australian National Maritime Museum, “won the admiration and envy of the world. Hundreds of Yankee clippers, long and lean, with a beautiful shape, and acres of canvas sails roamed the globe carrying passengers and freight.” The end of the high shipping fees in 1855, though, sunset the era of the clippers, says Lienhard.

The origin of the clipper ship can be found in the mindset of the 19th century entrepeneur that was driven by market competition and profit. Profits depended on how quickly a cargo reached the market. This created a demand for fast vessels and a willingness to push the boundaries of design and technology.

Now, those same market forces are pushing shipping technology once more—tying the old to the new in a bid to face new challenges with old ideas.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)