Scientific American in 1875: Eating Horse Meat Would Boost the Economy

Where did our aversion to horse meat come from, and why did Scientific American think we should eat it anyway?

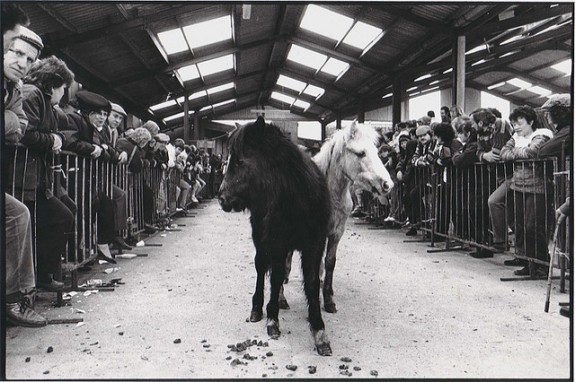

Ponies up for sale at the Llanybydder horse mart. Photo: Sheffpixie

Ikea’s delectable little meatballs have been found to contain horse meat, in addition to the advertised pork and beef—at least in the Czech Republic, reports the Guardian. In the past few weeks, traces of horse meat have shown up in beef products across Europe, in supermarkets and fast-food restaurants. But with Ikea now involved, these findings take on a whole new import. “Given the chain’s international reach,” says Quartz’s Christopher Mims, “this might be the point at which Europe’s horse meat scandal becomes global.”

Though the news may rankle some modern sensibilities, people have been debating the merits of eating horse meat for a surprisingly long time. Under siege in the 19th century, with rations running low, Paris’ population turn to horse. Though initially hesitant, some Frenchmen went on to develop a fondness for the taste, says a December 1, 1870 story in The Food Journal:

The almost impossibility of obtaining beef and mutton naturally forced the use of horse-meat upon the people, and, after a little hesitation, it has been most cheerfully accepted. Some persons prefer it to beef, from the gamey flavour which it possesses, and compare it to chevreuil—the small doe venison of France—which certainly scarcely deserves the name; others particularly dislike it for the same reason. This is, however, simple a matter of taste. As good wholesome food it has been universally eaten, and the soup made from it is declared by everyone to be superior to that from beef.

The end of the siege did not bring the end of horse meat, and over time, the idea spread. Scientific American‘s volume XXXIII, published on July 3, 1875, included a piece making the case for horse meat as economic stimulus.

We have spoken from time to time of the progress of hippophagy in Paris, regarding the same as an experiment which there was no particular need of putting into practice here. It may nevertheless be demonstrated that, in not utilizing horse flesh as food, we are throwing away a valuable and palatable meat, of which there is sufficient quantity largely to augment our existing aggregate food supply. Supposing that the horse came into use here as food, it can be easily shown that the absolute wealth in the country would thereby be materially increased.

The downside, of course, is that a horse cut up for food is not a horse doing valuable work. But even here, Scientific American thinks that the good of dining on horse far outweighs the bad.

Moreover, in order that the horses should be available to the butcher, they must not be diseased or worn out. By this the owners are directly benefited, since, while on one hand they are obliged to sell their horses in fair condition, they are saved the expense of keeping the animals when the latter become used up and are unable to do but light work, though requiring more attention and more feed. So also with colts, which, whether they become good or bad horses, cost about the same to raise. If the animal bids fair to turn our poorly, he can be disposed of at once and at a remunerative price. The result of this weeding out in youth and destroying when old, coupled with the facilities which the former afford of selection of the best types, will naturally conduce to the improvement of breeds and a general benefit to the entire equine population of the country.

Nineteenth century horse eugenics aside, the case for eating horse in the 1800s are roughly the same as now, says the New York Times: it all comes down to price.

But from whence came the modern hesitation to dine on horse? The September 1886 edition of Popular Science may have the answer:

The origin of the use of horse-flesh as food is lost in the night of the past. The ancients held the meat in high esteem, and a number of modern peoples use it unhesitatingly. Several Latin and Green authors mention it. Virgil, in the third book of the “Georgics,” speaks of peoples who live on the milk, blood, and meat of their horses.

… While horse-flesh was generally eaten among the Germans till they were converted to Christianity, or till the days of Charlemagne, it was regarded with aversion by the early Christians as a relic of idolatry. Gregory III, in the eighth century, advised St. Boniface, Archbishop of Mayence, to order the German clergy to preach against horse-eating as unclean and execrable. This prohibition being ineffective, Pope Zachary I launched a new anathema against the unfaithful “who eat the meat of the horse, hare, and other unclean animals.” This crusade was potent over the defectively informed minds of the people of the middle ages, and they, believing the meat to be unwholesome and not fit to eat, abstained from it except in times of extreme scarcity. Nevertheless, it continued to be eaten in particular localities down to a very recent period. The present revival in the use of horse-flesh, concerning which the French papers have had much to say, is the result of a concerted movement among a number of prominent men, the principal object of which was to add to the food resources of the world.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)