With Hybrid Embryo, Scientists Are One Step Closer to Saving the Northern White Rhino

Hybrid embryos were created using northern rhinos’ frozen sperm, southern rhinos’ eggs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/04/3e04d98c-d74c-4709-b424-ad299ac92b27/screen_shot_2018-07-05_at_111225_am.png)

In 1960, roughly 2,000 northern white rhinos roamed central Africa. Now, only two members of the species remain—a 28-year-old female named Najin and her 18-year-old daughter Fatu, both of whom are housed at a Kenyan animal conservancy under constant armed guard.

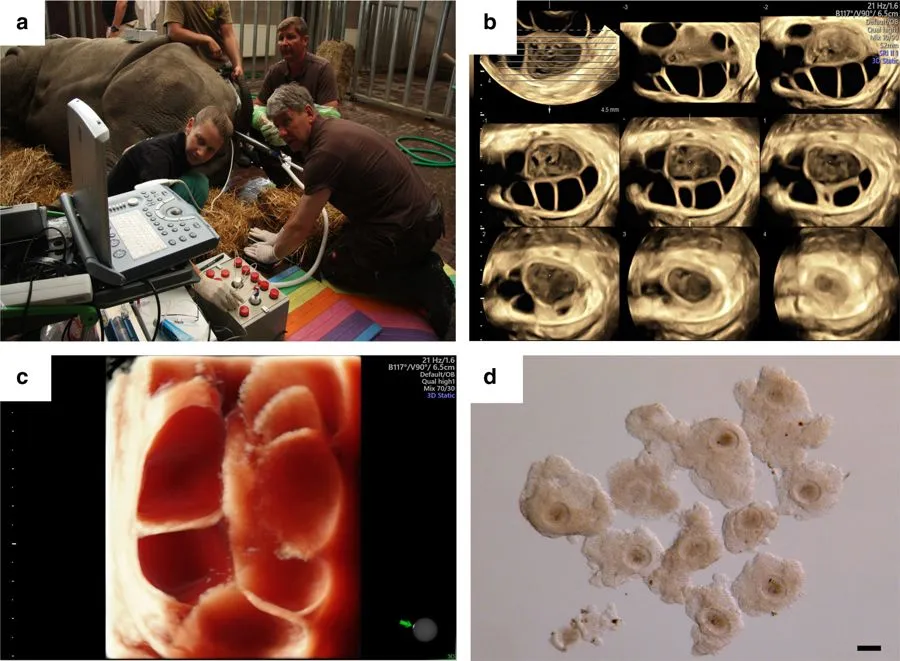

The outlook for the species is dire: Both mother and daughter are infertile, and the last surviving male, Sudan, died in March at age 45. Still, scientists remain cautiously optimistic. In a study published Wednesday in Nature Communications, researchers announced that they have successfully fertilized southern white rhinoceros eggs with frozen northern white rhinoceros sperm, thereby creating hybrid embryos.

The southern white rhinoceros is closely related to the northern subspecies and, according to the World Wildlife Fund, is the only surviving rhino species classified as not endangered. The Washington Post’s Ben Guarino reports that to produce the hybrid embryos, scientists retrieved the southern females’ eggs with a 60-inch-long instrument that enables the collection of ovarian tissue. These eggs were then fertilized in petri dishes with previously frozen samples of northern males’ sperm.

According to the New York Times’ Steph Yin, the team of international scientists drew on samples from four northern males and two southern females, ultimately creating four hybrid embryos and three full southern white embryos. The next step is to implant these embryos into surrogate southern females over the coming months, paper co-author Cesare Galli tells Yin, hopefully triggering the birth of a healthy hybrid calf.

The Chicago Tribune’s Frank Jordans writes that scientists’ long-term goal is to harvest eggs from Najin and Fatu, thereby enabling them to create wholly northern rhino embryos. These would then be implanted in southern surrogates, as the remaining northern females are unable to carry embryos themselves.

“Our goal is to have a northern white rhino calf on the ground in three years,” lead author Thomas Hildebrant, a wildlife reproductive biologist at Germany’s Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, told reporters during a Tuesday press briefing. “They have a 16-month pregnancy, so that gives us a little more than a year to have a successful implantation.”

The rapid timeline will allow the fledgling rhino to be socialized by the two remaining northern rhinos, the Los Angeles Times’ Deborah Netburn explains.

In addition to experimenting with the hybrid and northern embryos, scientists are working to turn samples of the rhinos’ skin cells into egg and sperm cells. This method has previously been used successfully with mice. The good news, Hildebrandt tells the New York Times’ Yin, is that researchers have a genetically diverse collection of cells to draw from and have already created 12 of these “reprogrammed” cells (albeit no egg or sperm cells). The drawback to the process, however, is that it will take about a decade to develop.

Although the hybrid embryos mark a promising first step in restoring the southern rhinos’ northern counterpart, scientists warn that the birth of a hybrid calf—already an ambitious goal— will not be enough to ensure the species’ survival.

Susie Ellis, executive director of the International Rhino Foundation, tells Yin that there is “a long road from creating an embryo to having a viable birth—and then an even longer path from succeeding once to creating a herd of rhinos.”

Hildebrandt is cognizant of the risks associated with the project, but he remains confident in its value for rhino preservation efforts—particularly if fertilization occurs in conjunction with anti-poaching initiatives.

"The northern white rhino didn't fail in evolution," Hildebrand told reporters. "It failed because it's not bulletproof. It was slaughtered by criminals which went for the horn because the horn costs more than gold."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)