Scientists Identify Blue Hues in Fossilized Bird Feathers for the First Time

A new study shows how the shapes of tiny pigment-carrying structures called melanosomes are associated with different colors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/65/a16563e3-3808-4ac6-b820-0bd24f20f3ac/062519_cg_fossil-feat.jpg)

A prehistoric Eocoracias brachyptera bird whose fossilized remains were recovered from Germany’s Messel Pit some 48 million years after its demise boasts the oldest evidence of blue plumage identified to date, according to a new study in Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

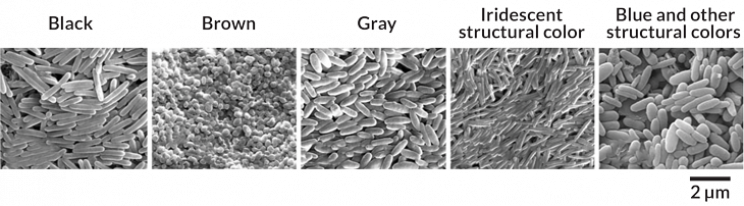

Researchers led by Frane Babarović, a Ph.D. student at England’s University of Sheffield, report that blue-hued feathers—now reconstructed from the fossil record for the very first time—can be differentiated from iridescent, brown, black and reddish-brown shades by taking a closer look at tiny pigment sacs called melanosomes. As Michael Greshko explains for National Geographic, black feathers have sausage-shaped melanosomes, while red-brown ones have a meatball-esque appearance. Those associated with blue plumage, however, are much longer than they are wide and bear a marked resemblance to melanosomes involved in the production of the color gray.

“We have discovered that melanosomes in blue feathers have a distinct range in size from most … colour categories and we can, therefore, constrain which fossils may have been blue originally,” Babarović says in a press release. “The overlap with grey colour may suggest some common mechanism in how melanosomes are involved in making grey colouration and how these structural blue colours are formed.”

Blue as a color is both harder to achieve and to discern. According to Earth.com’s Kay Vandette, blue birds’ feathers contain blue light-scattering cavities. It is impossible, therefore, to determine whether a bird boasted blue plumage without studying the dark melanin pigments responsible for absorbing the remaining unscattered light.

Although blue, green and color-shifting iridescent feathers—as seen in peacocks and hummingbirds—share a specific structure consisting of a layer of spongy keratin and another of pigment-carrying melanosomes, Science News’ Carolyn Gramling points out that these so-called structural colors can be further broken down into iridescent and non-iridescent groups.

Blue, which is non-iridescent, actually has three separate layers: an outer keratin covering, a spongy middle section and an interior layer of melanosomes, as National Geographic's Greshko notes. Whereas iridescent feathers reflect different colors at different angles, non-iridescent ones rely on their multi-layered structure to create a consistent color experience.

“The top layer is structured in such a way that it refracts light in blue wavelength,” Babarović tells Gramling. The melanosomes beneath this layer, meanwhile, absorb the remaining light, keeping the feathers from appearing iridescent.

Keratin doesn’t fossilize well, but melanosomes often do. In fact, National Geographic’s Greshko writes, fossilized pigment sacs have already been recovered from an array of prehistoric creatures, including non-avian dinosaurs, marine reptiles and various bird species.

By drawing on this abundant data source, Babarović and his colleagues set out to discover whether a specific melanosome shape could be associated with non-iridescent blue. Their findings, potentially indicative of an evolutionary link between gray and blue, make it more difficult to determine whether an ancient specimen was one color versus the other, actually lowering the accuracy of previous predictive models of fossil color from 82 percent to 61.9 percent.

Still, Science News’ Gramling notes, this uncertainty can be mitigated by looking toward extinct animals’ modern-day relatives. In the case of E. brachyptera specifically, contemporary counterparts including the Old World family of rollers, kingfishers and kookaburras all have blue feathers, making it extremely likely that their ancient ancestor had a deep blue hue, too.

Moving forward, the researchers hope to gain a better understanding of why blue emerged as an evolutionary option and exactly what role it plays in avian creatures’ livelihood.

“It’s something that hasn’t been explored as much,” Klara Norden, an evolutionary biologist at Princeton University who was not involved in the study, concludes to Gramling. “No one’s really looked at non-iridescent structural colors before at a large scale, because we’ve never had this dataset before. It’s really exciting to have this study out there that shows the shape of these melanosomes.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)