Have Scientists Finally Unraveled the 60-Year Mystery Surrounding Nine Russian Hikers’ Deaths?

New research identifies an unusual avalanche as the culprit behind the 1959 Dyatlov Pass Incident

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/88/32881615-82e9-4616-98c4-9515e86e3f4b/dyatlov_pass_incident_02.jpg)

In February 1959, university student Mikhail Sharavin made an unexpected discovery on the slopes of the Ural Mountains.

Dispatched as a member of a search party investigating a group of nine experienced hikers’ disappearance, Sharavin and his fellow rescuers spotted the corner of a tent peeking out beneath the snow, as he told BBC News’ Lucy Ash in 2019. Inside, they found supplies, including a flask of vodka, a map and a plate of salo (white pork fat), all seemingly abandoned without warning. A slash in the side of the tent suggested that someone had used a knife to carve out an escape route from within, while footprints leading away from the shelter indicated that some of the mountaineers had ventured out in sub-zero temperatures barefoot, or with only a single boot and socks.

Perplexed, the search party decided to toast to the missing group’s safety with the flask found in their tent.

“We shared [the vodka] out between us—there were 11 of us, including the guides,” Sharavin recalled. “We were about to drink it when one guy turned to me and said, ‘Best not drink to their health, but to their eternal peace.’”

Over the next several months, rescuers recovered all nine hikers’ bodies. Per BBC News, two of the men were found barefoot and clad only in their underwear. While the majority of the group appeared to have died of hypothermia, at least four had sustained horrific—and inexplicable—injuries, including a fractured skull, broken ribs and a gaping gash to the head. One woman, 20-year-old Lyudmila Dubinina, was missing both her eyeballs and her tongue. The wounds, said a doctor who examined the bodies, were “equal to the effect of a car crash,” according to documents later obtained by the St. Petersburg Times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/08/dc088318-b4cb-4dd0-9a55-74f3f5974384/2560px-____.jpg)

Today, the so-called Dyatlov Pass Incident—named after the group’s leader, 23-year-old Igor Dyatlov—is one of Russia’s most enduring mysteries, spawning conspiracy theories as varied as a military cover-up, a UFO sighting, an abominable snowman attack, radiation fallout from secret weapons tests and a clash with the indigenous Mansi people. But as Robin George Andrews reports for National Geographic, new research published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment points toward a more “sensible” explanation, drawing on advanced computer modeling to posit that an unusually timed avalanche sealed the hikers’ fate.

“We do not claim to have solved the Dyatlov Pass mystery, as no one survived to tell the story,” lead author Johan Gaume, head of the Snow and Avalanche Simulation Laboratory at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, tells Live Science’s Brandon Specktor. "But we show the plausibility of the avalanche hypothesis [for the first time]."

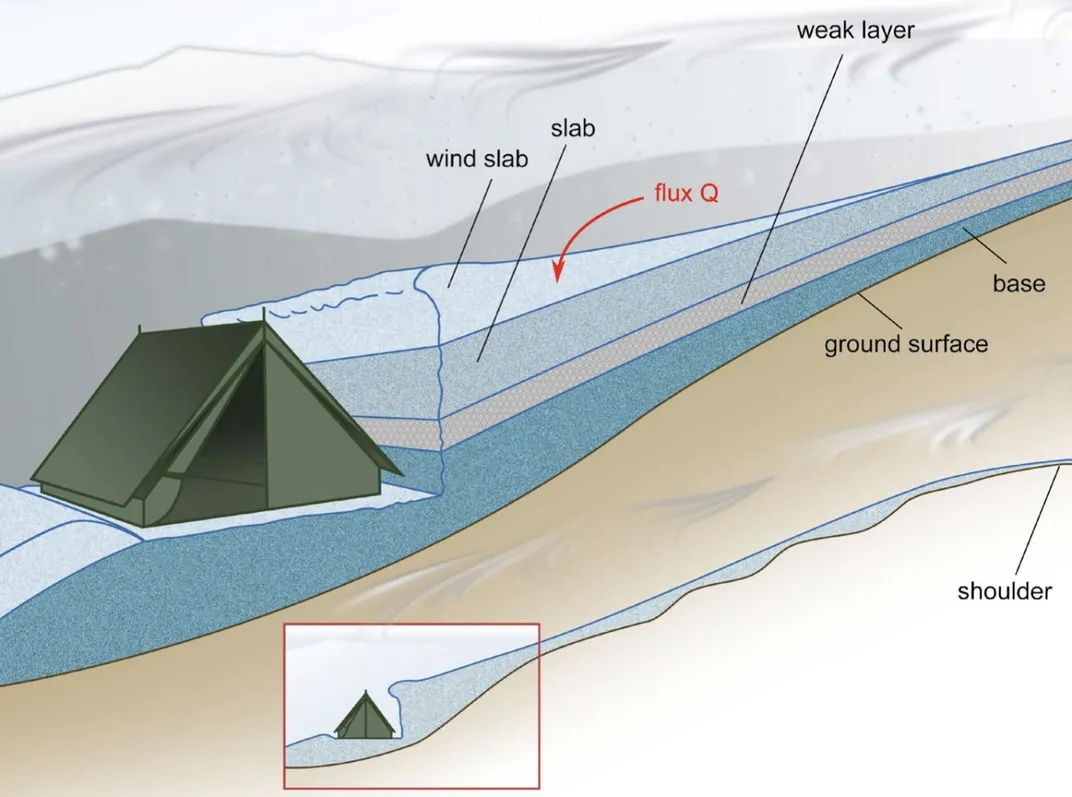

In 2019, Russian authorities announced plans to revisit the incident, which they attributed not to a crime, but to an avalanche, a snow slab or a hurricane. The following year, the inquiry pinned the hikers’ deaths on a combination of an avalanche and poor visibility. As the state-owned RIA news agency reported in July 2020, the official findings suggested that a torrent of snow slabs, or blocky chunks, surprised the sleeping victims and pushed them to seek shelter at a nearby ridge. Unable to see more than 50 feet ahead, the hikers froze to death as they attempted to make their way back to their tent. Given the official findings’ lack of “key scientific details,” as well as the Russian government’s notorious “lack of transparency,” however, this explanation failed to quell the public’s curiosity, per National Geographic.

Critics of the slab avalanche theory cite four main counterarguments, says Gaume to Live Science: the lack of physical traces of an avalanche found by rescuers; the more than nine-hour gap between the hikers building their camp—a process that required cutting into the mountain to form a barrier against the wind—and their panicked departure; the shallow slope of the campsite; and the traumatic injuries sustained by the group. (Asphyxiation is a more common cause of death for avalanche victims.)

Gaume and co-author Alexander M. Puzrin, a geotechnical engineer at ETH Zürich, used historical records to recreate the mountain’s environment on the night of the Dyatlov incident and attempt to address these seeming inconsistencies. Then, the scientists write in the study, they simulated a slab avalanche, drawing on snow friction data and local topography (which revealed that the slope wasn’t actually as shallow as it had seemed) to prove that a small snowslide could have swept through the area while leaving few traces behind.

The authors theorize that katabatic winds, or fast-flowing funnels of air propelled by the force of gravity, transported snow down the mountain to the campsite.

“[I]t was like somebody coming and shoveling the snow from one place and putting it on the slope above the tent,” Puzrin explains to New Scientist’s Krista Charles.

Eventually, the accumulating snow became too heavy for the slope to support.

“If they hadn’t made a cut in the slope, nothing would have happened,” says Puzrin in a statement. “[But] at a certain point, a crack could have formed and propagated, causing the snow slab to release.”

The researchers unraveled the final piece of the puzzle—the hikers’ unexplained injuries—with the help of a surprising source: Disney’s 2013 film Frozen. According to National Geographic, Gaume was so impressed by the movie’s depiction of snow that he asked its creators to share their animation code with him. This simulation tool, coupled with data from cadaver tests conducted by General Motors in the 1970s to determine what happened to the human body when struck at different speeds, enabled the pair to show that heavy blocks of solid snow could have landed on the hikers as they slept, crushing their bones and causing injuries not typically associated with avalanches. If this was the case, the pair posits, those who had sustained less serious blows likely dragged their injured companions out of the tent in hopes of saving their lives.

Jim McElwaine, a geohazards expert at Durham University in England who wasn’t involved in the study, tells National Geographic that the slabs of snow would have had to be incredibly stiff, and moving at a significant speed, to inflict such violent injuries.

Speaking with New Scientist, McElwaine adds that the research “doesn’t explain why these people, after being hit by an avalanche, ran off without their clothes on into the snow.”

He continues, “If you’re in that type of harsh environment it’s suicide to leave shelter without your clothes on. For people to do that they must have been terrified by something. I assume that one of the most likely things is that one of them went crazy for some reason. I can’t understand why else they would have behaved in that way unless they were trying to flee from someone who’s been tracking them.”

Gaume, on the other hand, views the situation rather differently.

As he tells Live Science, “When [the hikers] decided to go to the forest, they took care of their injured friends—no one was left behind. I think it is a great story of courage and friendship in the face of a brutal force of nature.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)