Scientists Published Henrietta Lacks’ Genome Without the Consent of Her Family

Author Rebecca Skloot argues that society is not ready for full genetic disclosures of individuals

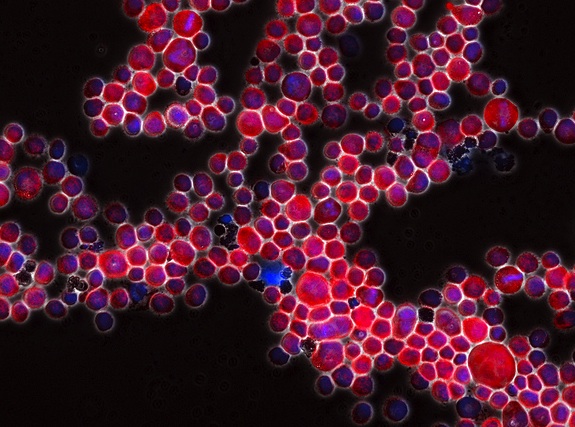

HeLa cells photographed in a laboratory. Photo: Euan Slorach

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a poor black mother of five living near Baltimore, died from cancer. But cells taken from her tumor lived on. The so-called HeLa cells multiplied prolifically and were sent to labs around the world, where they went on to help develop medical innovations and understanding about vaccines, cancer treatments, cloning and more.

Lacks’ story also raised significant questions about medical ethics. Lacks’ family was never informed that her cells lived on or even that a sample had been taken from her tumor. They only learned about the HeLa cells about twenty years later, by chance, and researchers used the family for HeLa studies without fully explaining what was going on.

In the story’s latest development, last week scientists published Lacks’ full genome—again, without consent of her family. Journalist Rebecca Skloot, who told the story of the HeLa cells in her best-selling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, responds to this in an op-ed published in The New York Times:

Genetic information can be stigmatizing, and while it’s illegal for employers or health insurance providers to discriminate based on that information, this is not true for life insurance, disability coverage or long-term care.

Uploading a person’s genetic code onto the website SNPedia, for example, can reveal all sorts of personal information about her and her family within minutes, Skloot explains.

Scientifically speaking, that’s good news. There’s a lot of hope for using technology like this for affordable “personalized medicine.” But legally and ethically speaking, we’re not ready for it.

After hearing from the Lacks family, the European team apologized, revised the news release and quietly took the data off-line. (At least 15 people had already downloaded it.) They also pointed to other databases that had published portions of Henrietta Lacks’s genetic data (also without consent). They hope to talk with the Lacks family to determine how to handle the HeLa genome while working toward creating international standards for handling these issues.

As David Kroll points out in Forbes, legally the researchers who published the study were not required to consult with Lacks’ family. Laws requiring consent from offspring when a person or scientist choses to publish their genome do not exist.

Both Skloot and Kroll call for a reinvention of current standard procedure governing such issues, specifically one that focuses more on consent and trust.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)