The Scottish Garden That Inspired Peter Pan’s Neverland Opens for Visitors

The Moat Brae house and its surroundings, where author J.M. Barrie played as a child, is now a children’s literature center

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/ae/06aea06d-1bd9-418a-8f5b-564df5bd517e/tinker_bell_at_moat_brae_house_dumfries_02.jpg)

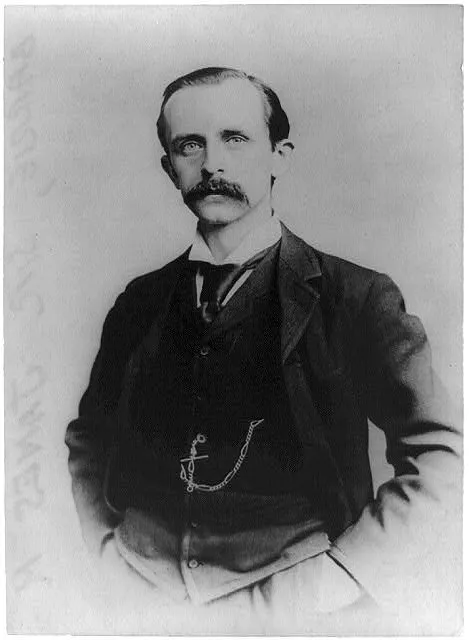

When he was 13 years old, J.M. Barrie entered the Dumfries Academy in Scotland, where he became fast friends with a pair of brothers named Stuart and Hal Gordon. In the garden of the Gordon family home, an elegant villa called Moat Brae, the three boys scampered about playing pirates and other games. As an adult, Barrie referred to the garden as an “enchanted land” and credited it as an inspiration for “that nefarious work”—Peter Pan.

Following a years-long and multi-million dollar restoration effort, the home where Barrie frolicked as a boy is reopening as a children’s literature facility, reports Libby Brooks of the Guardian. At the redeveloped Moat Brae house, which is located in the town of Dumfries in southwest Scotland, young visitors will find toys, indoor and outdoor play spaces and a collection of thousands of donated books. But the National Centre for Children’s Literature and Storytelling—the first of its kind in the country—almost never came to be.

Just eight years ago, Moat Brae was slated for destruction. The property, which was converted into a nursing home in the early 20th century, had fallen into a state of disrepair, and the site was due to be reallocated to an affordable housing project. Hoping to save this neglected relic of Scottish literary history, a group now known as the Peter Pan Moat Brae Trust sprang into fundraising action and put a stop to the demolition just days before it was scheduled to take place.

The renovation project, which cost £8.5 million (more than $10 million), involved both the restoration of the 19th century house and the creation of a modern extension. Opening to the public on June 1, Moat Brae now includes interactive exhibitions featuring, among other things, the bell that was rung whenever Tinker Bell made an appearance in the original stage version of Peter Pan; a library and reading spaces; and a recreation of the Darling children’s nursery. In the gardens where Barrie once played, little ones will find a pirate ship, a “Lost Boys’ treehouse,” adventure trails and spaces for studying plants, and other attractions.

Dame Barbara Kelly, an actor and chair of the Peter Pan Moat Brae Trust, told the BBC that the opening of the center marks “a great day for Dumfries”—a place where Barrie spent several happy years during what was otherwise a difficult childhood. In 1867, when Barrie was six years old, his older brother, David, was killed when he fractured his skull in an ice skating accident. The tragic event sent his mother’s mental health plummeting, and “Barrie never recovered from the shock ... and its grievous effect on his mother, who dominated his childhood,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

But in 1873, Barrie temporarily moved from his hometown of Kirriemuir to Dumfries, where he lived with another of his older brothers (there were ten children in the Barrie family). Barrie was not an exceptional student at Dumfries Academy, but he was an energetic participant in the school’s extracurriculars: athletics, debating, drama. It was while studying at Dumfries Academy that Barrie wrote his first play, called Bandelero the Bandit. He and his friends belonged to an imaginary “pirate crew;” Stuart Gordon, who he befriended at Dumfries Academy, gave him the nickname “Sixteen String Jack.”

“I think the five years or so that I spent here were probably the happiest of my life,” Barrie once said of Dumfries, “for indeed I have loved this place.”

With the restoration of Moat Brae, a new generation of readers will be able to explore one of the spaces where Barrie’s creativity flourished in the years before he became a beloved children’s author. The home, says Moat Brae director Simon Davidson, has been “brought back to life ... in order to spark the imaginations of many thousands of young people from every corner of the world.”