Another Long-Lost Jacob Lawrence Painting Resurfaces in Manhattan

Inspired by the recent discovery of a related panel, a nurse realized that the missing artwork had hung in her house for decades

:focal(972x1010:973x1011)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/e8/63e8d222-938d-4496-812b-4831bfc0921b/aaa-aaa_valealfr_4483.jpg)

Last October, shock and excitement rippled through the art world after a couple living in New York City realized that an artwork hanging in their living room was actually a missing masterpiece by groundbreaking black Modernist painter Jacob Lawrence.

Experts soon identified the painting as one of five missing works from Lawrence’s Struggle: From the History of the American People (1954–56) series, a sweeping, 30-panel sequence that recounts American history with a radical focus on the stories of women, people of color and working-class individuals.

In another shocking turn of events, curators at Massachusetts’ Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) announced this week that a second lost panel from Struggle has resurfaced, once again in New York City. A nurse living on the Upper West Side kept Panel 28, which had been presumed lost since the 1960s, hanging on her dining room wall for two decades—mere blocks away from its other forgotten companion, reports Hilarie M. Sheets for the New York Times.

The earlier discovery took place as a result of PEM’s ongoing exhibition of Struggle, which traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art last fall. (Viewers can explore an interactive version of the exhibition through the Salem museum’s website.)

One visitor to the Met happened to notice that the vibrant colors and shapes of Lawrence’s compositions bore a striking resemblance to a painting she’d seen in her neighbors’ living room. She encouraged the couple to approach the museum’s curators, who identified the artwork as the series’ long-lost Panel 16. Titled There are combustibles in every State, which a spark might set fire to. —Washington, 26 December 1786, the painting depicts the events of Shay’s Rebellion, a six-month armed uprising led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays in protest of Massachusetts’ heavy taxation of farmers.

Two weeks after that spectacular discovery made headlines, another woman also living in an Upper West Side apartment read about the find on Patch, a neighborhood app. She realized that a painting hanging in her dining room might be a second missing panel. (The owners of both works have requested anonymity.)

Now in her late 40s, the woman immigrated to the United States from Ukraine when she was 18. Her mother-in-law gave her the painting two decades ago. Taped to the back of its frame was a clue: a 1996 New York Times profile of Lawrence, who died four years later, in 2000.

“It didn’t look like anything special, honestly,” the owner tells the Times. “The colors were pretty. It was a little bit worn. I passed by it on my way to the kitchen a thousand times a day. … I didn’t know I had a masterpiece.”

The owner and her 20-year-old son, who studied art in college, did some digging online to confirm that their painting might be the real deal. After three days of waiting for the Met to return their phone calls, the pair visited the museum in person to share their find.

Curators quickly determined that the panel was legitimate, even revealing new details about its history. Though the missing work had been listed in catalogs as Immigrants admitted from all countries: 1820 to 1840—115,773, Lawrence had actually written an alternative title on the back of the canvas: The Emigrants — 1821-1830 (106,308).

Per the Times, the artist created the panel after reading immigration statistics in Richard B. Morris’ 1953 Encyclopedia of American History.

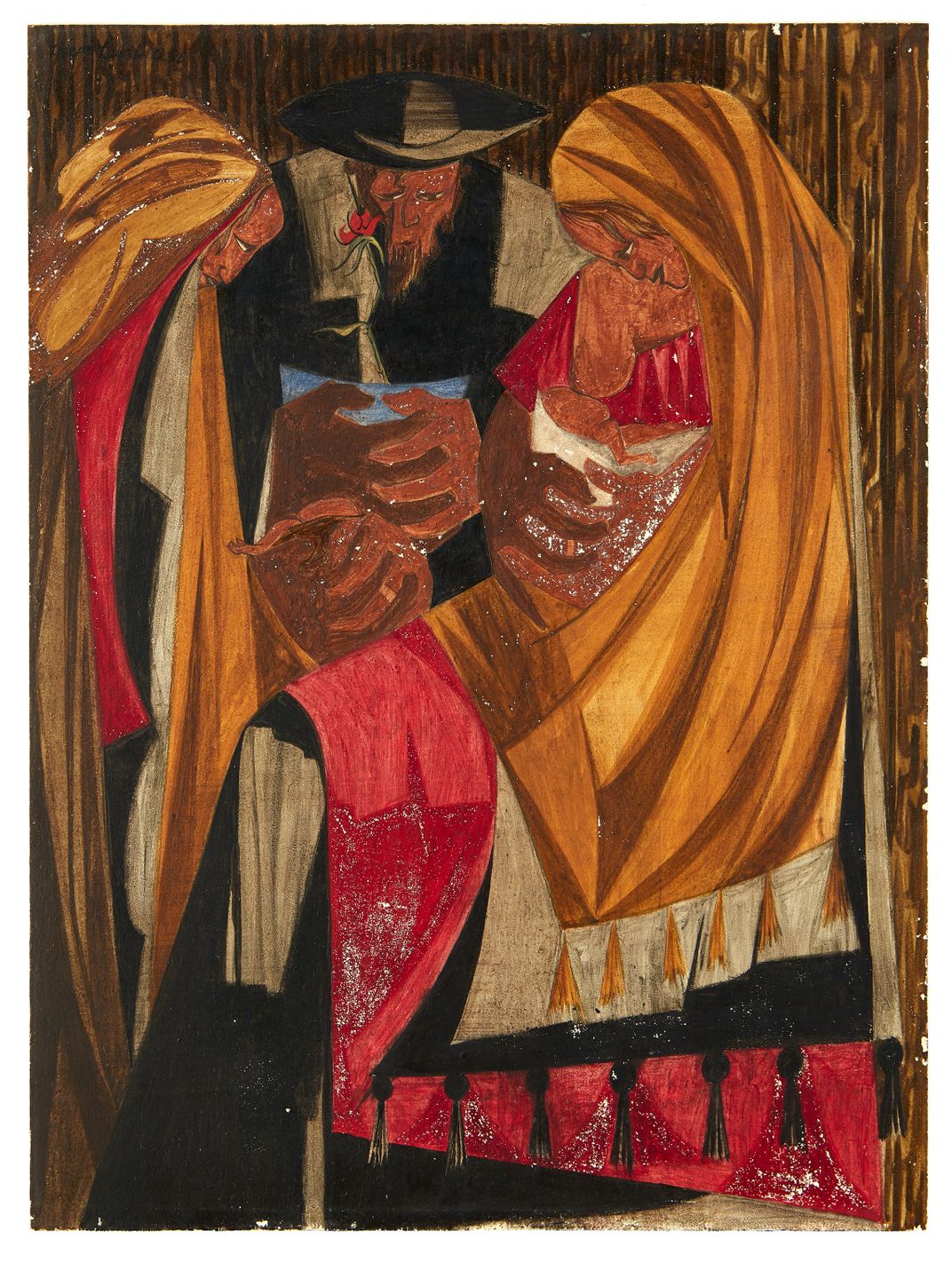

The composition depicts three bowed figures: two women in head scarfs holding babies and a man in a wide-brimmed black hat. The owner’s son pointed out to curators that the man is not holding a prayer book, as written in some texts, but rather cradling a large flowerpot with a single red rose.

“We’re now able to see so much more of this tender hope and optimism—this symbolism of fragile life growing in the new place for these people that have emigrated,” Lydia Gordon, coordinating curator of the PEM exhibition, tells the Times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/7a/7f7abba0-52de-4335-b52c-8ac58661fb92/926265741.jpg)

Lawrence was born in Atlantic City in 1917. He came of age in 1930s New York and was greatly inspired by the ethos and cultural innovation of the Harlem Renaissance, as Anna Diamond reported for Smithsonian magazine in 2017. As his practice evolved, Lawrence began to paint scenes that told American history through the stories of famous black Americans, including Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. His most famous work, a monumental, 60-panel series on the Great Migration, recounted the social, economic and political change that occurred when more than one million African Americans moved from the rural South to the industrial North following World War I.

As Brian Boucher reports for Artnet News, an “ill-advised collector” purchased Struggle and sold the works individually during the mid-20th century. The couple who owned Panel 16 purchased the work for about $100 at a local Christmas art auction in the 1960s. As the Times reports, the woman who owns Panel 28 suspects that her mother-in-law may have purchased the work around the same time for a similar price.

“Is there a possibility they were bought at the same auction?” she asks. “I think there’s a very good chance.”

Panel 28 will be reunited with the rest of the series for the touring exhibition’s final stops at the Seattle Art Museum and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. The location of three other missing works—Panel 14, Panel 20 and Panel 29—remains unknown. Curators urge anyone with information about the lost masterpieces to email their tips to [email protected].

Gordon says that she expects the panels to turn up eventually—possibly on the West Coast, in the collections of the many students and curators who worked with Lawrence. (The artist lived in Seattle for the last three decades of his life.)

“Oh, we’re totally going to find them!” she tells the Times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)