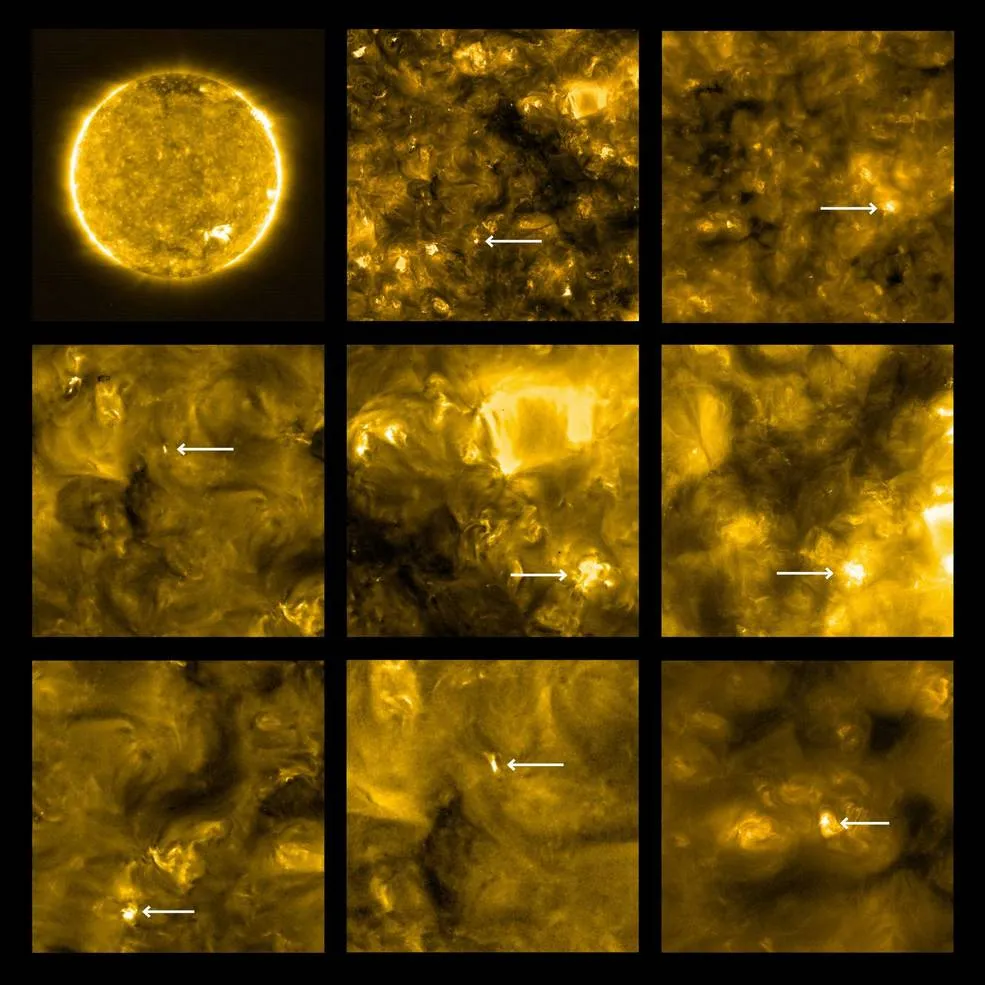

See Our Sun’s Surface in Unprecedented Detail

NASA and the European Space Agency released the closest images ever taken of our sun

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/b1/dab17fe6-cafd-4f55-a050-3d0ccc54c57b/solar_orbiter-eui_0.gif)

Our sun’s surface is rarely calm. Even now, when the star is in its phase of relative inactivity known as the “solar minimum,” the surface will light up with a rare solar flare or darken with the occasional sunspot.

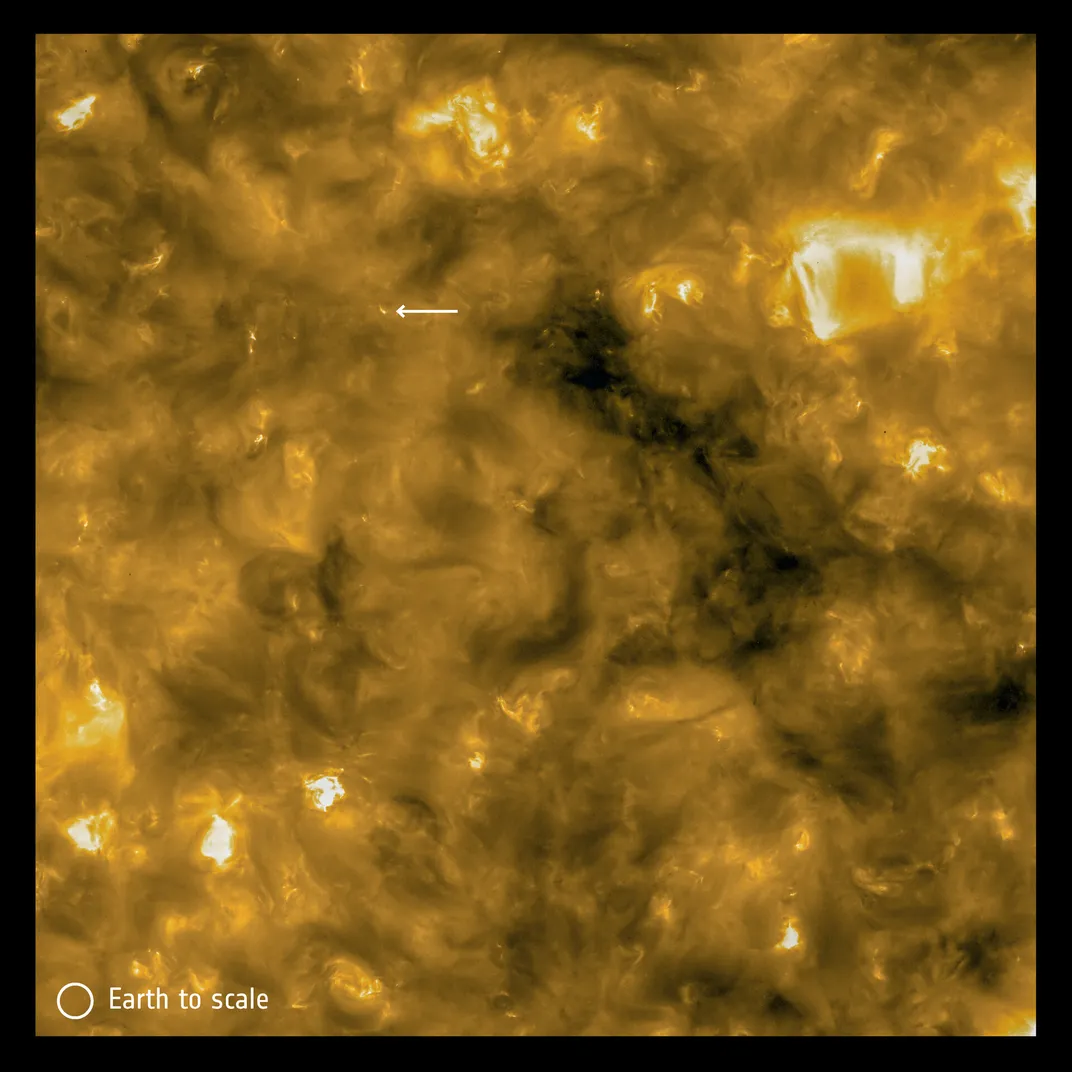

Last month, scientists took images of the sun that revealed its surface activity in unprecedented detail, in dramatic swirls of grey and yellow. The researchers also witnessed a surprising phenomenon: a spate of mini-flares, dubbed “campfires,” that seem to take place everywhere on the sun’s surface.

NASA and the European Space Agency captured the images—the closest ever taken of the sun—in May and June, according to a statement.

“These unprecedented pictures of the Sun are the closest we have ever obtained,” said Holly Gilbert, a project scientist with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in the statement. “These amazing images will help scientists piece together the Sun’s atmospheric layers, which is important for understanding how it drives space weather near the Earth and throughout the solar system.”

Solar Orbiter, the spacecraft that captured the images, is a joint mission between NASA and the ESA, reports Kenneth Chang for the New York Times. The craft launched on February 9 and flew within 48 million miles of the Sun on June 15. (For context: the Earth orbits the Sun at an average of roughly 92 million miles, per Space.com.)

At one point during the mission, the COVID-19 pandemic forced many members of Space Orbiter mission control in Darmstadt, Germany, to work from home. The team had to figure out how to operate the spacecraft with only essential personnel in the building, per the NASA statement.

David Berghmans, the principal scientist for the team that captured the images and a researcher with the Royal Observatory of Belgium, tells the Associated Press’ Marcia Dunn that he was shocked by the first round of images. “This is not possible. It cannot be that good,” the scientist recalls thinking. “It was really much better than we expected, but what we dared to hope for,” says Berghmans.

After discovering the flares, the team had to come up with new terms to describe the phenomenon. “We couldn’t believe this when we first saw this. And we started giving it crazy names like campfires and dark fibrils and ghosts and whatever we saw,” Berghmans tells the Times.

The small flares are likely tiny explosions called nanoflares, according to an ABC News report. In an ESA statement, Berghmans explains that these flares are millions or billions times smaller than the solar flares that we witness from Earth.

Some scientists are speculating that the ubiquitious campfires might help explain the fact that the sun’s corona, or outer atmospheric layer, is magnitudes hotter than its actual surface—a phenomenon known as “coronal heating,” and one that has puzzled scientists for decades.

“It’s obviously way too early to tell but we hope that by connecting these observations with measurements from our other instruments that ‘feel’ the solar wind as it passes the spacecraft, we will eventually be able to answer some of these mysteries,” says Yannis Zouganelis, an ESA scientist who works on the Solar Orbiter, in a statement.

The teams plans to collect further measurements of the campfires. All told, Solar Orbiter is slated to complete 22 orbits around the sun in the next 10 years, according to the Times. It carries ten instruments that scientists are using to analyze the sun up-close, including cameras that selectively analyze the sun’s outer atmosphere and ones that measure ultraviolet light and X-rays.

Daniel Müller announced the news in a press conference held by the European Space Agency last week, reports Chang for the Times. “We’ve never been closer to the sun with a camera,” Müller said. “And this is just the beginning of the long epic journey of Solar Orbiter.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)