Geologists Map the Plumbing Beneath Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Geyser

Without turning over a stone, geologists imaged the subsurface supply for this iconic geyser

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/7b/187bf48a-6b34-4581-85f2-29c511fcdfdd/old_faithful_geyser_28.jpg)

Dubbed "Old Faithful" in 1870, this natural wonder produces bursts of water every 60 to 110 minutes that spurt more than 100 feet in the air. But exactly what supplies the regular eruptions of water? As Tim Appenzeller reports for Science, a new analysis digs into the question and maps out what lies beneath.

While the feature has been thoroughly and regularly studied for decades, researchers have only just started studying its plumbing. But that's far from easy to do. Scientists can't just start digging into the treasured land of a national park and standard tools used to map the near-surface geology of an area can be very disruptive.

For example, researchers often trigger seismic vibrations with explosions or so-called "thumper trucks" that pound the ground in predictable ways, allowing them to track how quickly waves move through the ground. This way, they can "image" the subsurface without actually seeing it. Those methods, however, weren't going to cut it for Old Faithful.

In the new study, published in the journal Geophysical Review Letters, geologists took a more passive tack, writes Sean Reichard of Yellowstone Insider. They scattered 133 seismographs across a 250-acre region surrounding Old Faithful to measure the tiny vibrations the water and steam make as they move underneath the geyser.

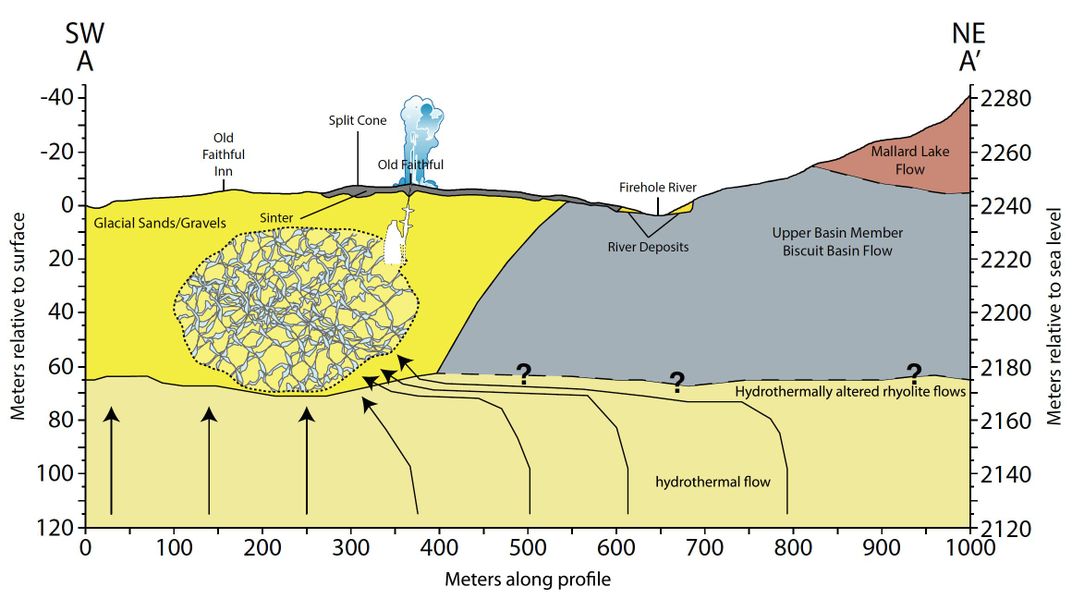

Over the course of two weeks, geologists tracked these tiny tremors using them to measure the reservoir beneath Old Faithful. It turns out it was surprisingly large, spanning more than 650 feet across and holding more than 79 million gallons of water—far more than the roughly 8,000 gallons released by the geyser in each of its eruptions. Water is heated by magma that underlies this massive chamber and as the pressure climbs the water is eventually ejected out of the surface cracks in a column of scorching-hot water.

"Although it’s a rough estimation, we were surprised that it was so large," lead author Sin-Mei Wu, a geologist at the University of Utah, says in a statement.

The researchers are already planning to bring out their inexpensive seismographs again later this year to get a more detailed picture of the ground beneath Yellowstone, Reichard writes, bringing more of the park's subsurface plumbing to light.