The Far-Reaching Consequences of Siberia’s Climate-Change-Driven Wildfires

Smoke from the blazes is now reaching the West Coast of the United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/38/4738a70f-387d-4774-9c46-aa4d6a0f198c/gettyimages-1217493137.jpg)

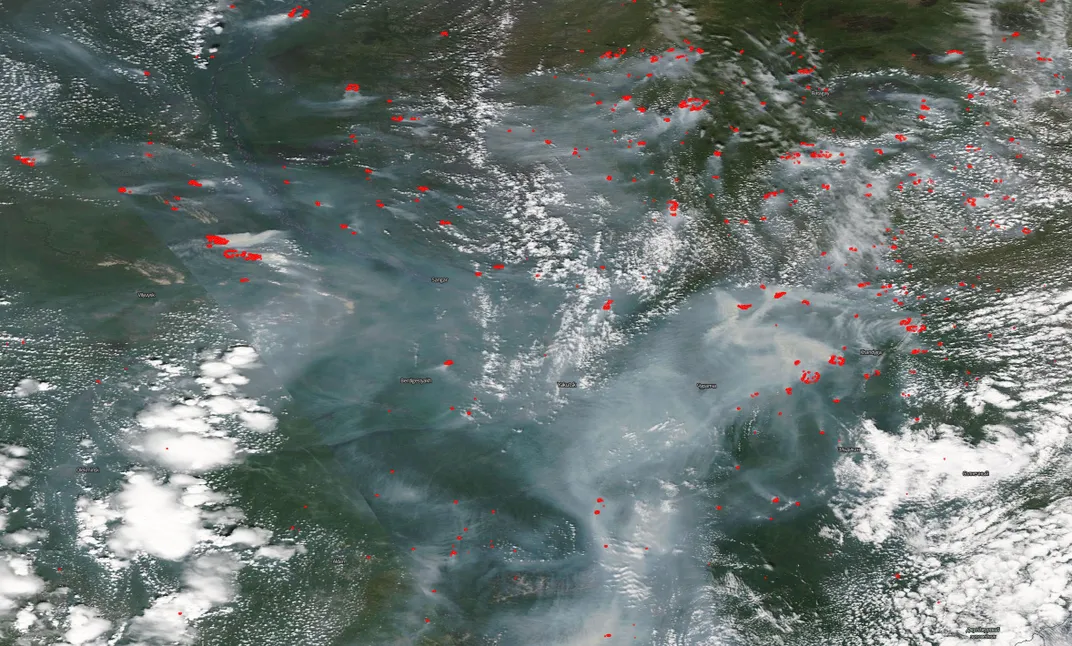

“Higher temperatures and drier surface conditions are providing ideal conditions for these fires to burn and to persist for so long over such a large area,” European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts fire specialist Mark Parrington says in a statement, per the New York Times. The smoke from the fires alone spans over 1,000 miles, per the Post, and is causing hazy skies the northwestern United States, as Nick Morgan reports for the Mail Tribune.

Permafrost is rich in organic material that froze before it could completely decompose. Melting permafrost releases greenhouse gases on top of the pollution released by the blazes themselves, per National Geographic. All of which could exacerbate further climate change.

After a month of blazes that released record-breaking amounts of polluting gases, smoke from Siberian wildfires are now making their way to the west coast of the United States.

The New York Times’ Somini Sengupta reports that Arctic wildfires in June released more pollution than in the previous 18 years that data had been collected. Seasonal wildfires are common in Siberia, but this year’s fires are unusually widespread in part because of a climate change-driven heatwave, as Madeleine Stone reports for National Geographic. The Arctic is experiencing climate change-driven warming faster than the rest of the Earth, which sets up the dry conditions that make blazes spread. While on average, the Earth’s temperature has risen by 1.71 degrees Fahrenheit, the Arctic has seen a rise of 5.6 degrees Fahrenheit, a discrepancy accounted for by Arctic amplification.

“I was a little shocked to see a fire burning 10 kilometers south of a bay of the Laptev Sea, which is like, the sea ice factory of the world,” Miami University in Ohio fire researcher Jessica McCarty tells National Geographic. “When I went into fire science as an undergraduate student, if someone had told me I’d be studying fire regimes in Greenland and the Arctic, I would have laughed at them.”

This June’s Arctic fires beat the pollution record set in 2019, Mark Parrington, who works with the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service tracking worldwide wildfires, tells the Washington Post. Some of the fires may have spent the winter months smoldering only to grow again in warmer weather, a phenomenon called “zombie fires.” And the weather has certainly gotten warmer: in June, a Russian town above the Arctic circle called Verkhoyansk hit a high temperature of 100.4 degree Fahrenheit.

The current situation in the Arctic circle shows that previous predictions “underestimate what is going on in reality,” University of Alaska at Fairbanks earth scientist Vladimir Romanovsky, who studies permafrost, tells the Washington Post. Romanovsky adds that temperature observations in the High Arctic made in the last 15 years weren’t expected for another seven decades.

Millions of acres of land are ablaze this wildfire season, according to Russia’s Forestry Agency estimates. Most of the wildfires are located in Siberia’s Sakha Republic, which sees wildfires frequently, but fires are also spreading further north and into unusual ecosystems, like those that are characterized by a layer of frozen soil called permafrost.